Eugene Ormandy was the irremovable musical director of the Philadelphia Orchestra for 44 years. He achieved instant notoriety in 1931 when he replaced the great Toscanini at the last minute. In 1936, he shared the music direction of the Philadelphia Orchestra, one of the three most famous American orchestras of the time, with Leopold Stokowski, and became its sole director two years later. This was in 1938, the same year that Eugene Istomin began his studies at the Curtis Institute. Istomin avidly attended countless rehearsals and concerts conducted by Ormandy, and dreamed of appearing as soloist one day with him! He did not have to wait too long. No sooner had he finished his studies than he won the coveted Youth Competition organized by the Philadelphia Orchestra and made his debut under Ormandy on November 17, 1943.

Eugene Ormandy was the irremovable musical director of the Philadelphia Orchestra for 44 years. He achieved instant notoriety in 1931 when he replaced the great Toscanini at the last minute. In 1936, he shared the music direction of the Philadelphia Orchestra, one of the three most famous American orchestras of the time, with Leopold Stokowski, and became its sole director two years later. This was in 1938, the same year that Eugene Istomin began his studies at the Curtis Institute. Istomin avidly attended countless rehearsals and concerts conducted by Ormandy, and dreamed of appearing as soloist one day with him! He did not have to wait too long. No sooner had he finished his studies than he won the coveted Youth Competition organized by the Philadelphia Orchestra and made his debut under Ormandy on November 17, 1943.

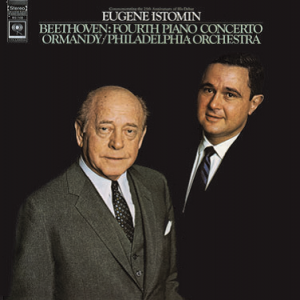

Strangely enough, Istomin would not perform with the Philadelphia Orchestra for the next ten years, due to the scheming of Olga Samaroff, Stokowski’s ex-wife and William Kapell’s teacher, who was anxious to keep her student’s greatest rival as far away as possible. Nevertheless, from 1953 to 1983, Istomin gave some eighty-five concerts with the Philadelphia Orchestra! Most of them were given in Philadelphia, at the Academy of Music, at Constitution Hall, or during summer residencies (Robin Hood Dell and Saratoga), but there were also a few tours and many concerts at Carnegie Hall. From 1956, all of Istomin’s concerto recordings were made with Ormandy, with the exception of the Schumann Concerto (which he recorded) with Bruno Walter.

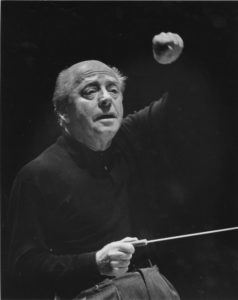

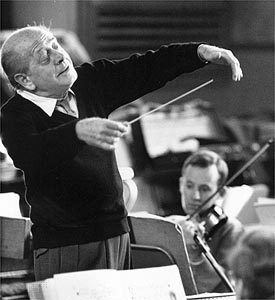

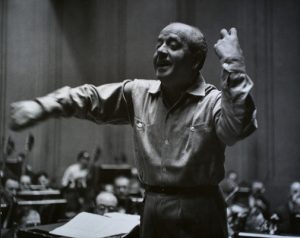

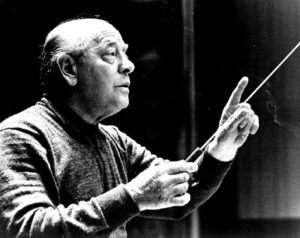

Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra on the stage of the Academy of Music

Istomin considered the Philadelphia Orchestra to be without question the best orchestra in the world. In addition to its outstanding virtuosity and ability to sight read and rapidly master even the most complex score, it was renowned for its sumptuous tone color. Ormandy had a reputation for being a remarkable accompanist, although he sometimes clashed with soloists and never re-engaged them. This was particularly true in the case of Leon Fleisher, who had had the audacity to request taking a few liberties in the score of the Rachmaninoff Second Concerto! Istomin said about Ormandy: “He had quicksilver reflexes. He could anticipate what everybody would do.”

A filial relationship

A sense of total complicity existed between Istomin and Ormandy. Their relationship was almost filial, even though Ormandy’s character tended to be quite cool and distant. Istomin even managed to convince him to vote for Humphrey in 1968, despite his previous pro-Republican convictions. Ormandy was willing to conduct a concert in support of Humphrey’s campaign as he had been moved by Istomin’s enthusiasm and loyalty to Humphrey. Eugene Ormandy and his wife showed an enduring sense of affection for Istomin throughout all the milestones of his life and career. The day after his marriage to Marta Casals, they wrote to him: “Eugene, you deserved a very special lady as your wife and we feel that there is no one whom you deserve more, or who deserves you more than Martita.” At his death, Ormandy bequeathed the cufflinks he wore when he conducted to Istomin, who subsequently gave them to his former student Jean-Bernard Pommier.

For Istomin, playing under Ormandy was at the same time a security and an inspiration. However, posterity did not acknowledge Ormandy as the eminent conductor he was. Already, at the end of his career, and perhaps because of his extremely long tenure in Philadelphia, his achievements were being disputed. Some questioned his responsibility for the lush sound of his orchestra, whereas Ormandy insisted: “The sound of the Philadelphia Orchestra, that’s mine”! The answer came after he resigned. It soon became impossible to recognize the Orchestra’s once-fabled sonority. Istomin was unhappy by this lack of acknowledgement. For him, Ormandy was a fantastic conductor and a great musician. He might give the impression that his interpretations did not speak in the first person. They did not search for deliberate originality, but they were nurtured by a profound understanding and respect for the score. This made them far more musical than those of many conductors who were excessively praised by the media.

Outside Philadelphia

Their collaboration was not confined to the Philadelphia Orchestra. Istomin was also Ormandy’s soloist with the Chicago Symphony, the Boston Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Eugene Istomin and Eugene Ormandy shared many exceptional moments together.

Their collaboration was not confined to the Philadelphia Orchestra. Istomin was also Ormandy’s soloist with the Chicago Symphony, the Boston Symphony and the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Eugene Istomin and Eugene Ormandy shared many exceptional moments together.

One of these was at the 1953 Prades Festival. Istomin had persuaded Casals to record Schumann’s Cello Concerto for Columbia, which he had never recorded before. Casals’ brother Enric was meant to conduct the orchestra, but things were not going well, and a great conductor had to be brought in. Some of the orchestra musicians vehemently rejected the idea of playing under George Szell, who was notorious for treating the instrumentalists with the utmost contempt. Istomin, who at the time was artistic director of the Prades Festival, decided to call on Ormandy, even though he had not extended an invitation to him for ten years. Ormandy agreed to conduct the Prades Festival Orchestra anonymously for this recording, due to his exclusive contract with RCA, and without taking a fee, as a tribute to Casals. It was a first rapprochement.

A few months later, Ormandy asked Istomin to replace his friend William Kapell, who had just been killed in a plane crash. It was an anguishing situation for Istomin, and his performance of the Beethoven Fourth Concerto was probably one of the most moving performances he ever gave (as witnessed by the live recording, despite the poor sound). According to the Philadelphia papers, the concert was a “thundering” success.

The last concerts

In 1980, Ormandy had just turned over the direction of the Philadelphia Orchestra to Riccardo Muti, but he was in charge of conducting the opening concert of Carnegie Hall’s 90th season in an exact replica of the program which the Philadelphia Orchestra had given for its first appearance in this hall in 1902. For the Tchaikovsky First Concerto, Ormandy absolutely wanted his soloist to be Eugene Istomin. He had just listened to the reissue of the recording they had made together years earlier, and found it wonderfully poetic. Istomin was reluctant, as he had not played the concerto for more than 15 years, but he did not have the heart to refuse, saying in an interview: “Ormandy is a father figure to me, and he can scold and cajole.” Istomin changed his entire schedule in order to prepare well, and devoted himself towards mastering this finger-breaking concerto once again. Even though Istomin could not totally recapture the fantastic virtuosity which he possessed twenty years ago, Ormandy was delighted with the result and its success. Peter Trump remarked: “Istomin’s interaction with the various soloists of the orchestra was a delight and spoke volumes for a long and absorbing interest in ensemble playing. Ormandy too lived up to his reputation as one of the world’s great accompanists. As they brought the concerto to a climatic conclusion, the effusive applause began with the final chords and lasted until the house lights were turned up.”

Three years later, Istomin played again with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Ormandy at Carnegie Hall on May 17, 1983. Istomin felt especially inspired, knowing that it would most likely be their ultimate collaboration. His performance of the Beethoven Emperor Concerto was received with tremendous acclaim. Harriett Johnson wrote in the New York Post: “Eugene Istomin, with his superb equipment, played like a master. He really found his best self in this Beethoven. He vitalized its grandeur and majesty with his in-depth virtuosity animated by a full, vibrant tone, perfectly produced. His Steinway sounded as if born to melody. Even the trills achieved substance-status. At the Concerto’s conclusion, the crowd was loath to let him out of sight.”

Three years later, Istomin played again with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Ormandy at Carnegie Hall on May 17, 1983. Istomin felt especially inspired, knowing that it would most likely be their ultimate collaboration. His performance of the Beethoven Emperor Concerto was received with tremendous acclaim. Harriett Johnson wrote in the New York Post: “Eugene Istomin, with his superb equipment, played like a master. He really found his best self in this Beethoven. He vitalized its grandeur and majesty with his in-depth virtuosity animated by a full, vibrant tone, perfectly produced. His Steinway sounded as if born to melody. Even the trills achieved substance-status. At the Concerto’s conclusion, the crowd was loath to let him out of sight.”

It was one of the very last concerts conducted by Ormandy, who died on March 12, 1985. For the third anniversary of his death, Istomin played Beethoven’s Quintet Op. 16 with the legendary wind soloists of the Philadelphia Orchestra (bassoonist Bernard Garfield, clarinetist Anthony Gigliotti, French horn player Nolan Miller and oboist Richard Woodhams).

Official recordings

1956, April 8. Rachmaninoff, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1956, April 8. Rachmaninoff, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1958, January 26. Beethoven, Concerto No. 5. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1959, April 19. Tchaikovsky, Concerto No. 1. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1959, November 1. Chopin, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1964, April 16. Beethoven, Triple Concerto. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1965, February 8 and 13. Brahms, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1968, December 15. Beethoven, Concerto No. 4. Philadelphia Orchestra. .

Concerts

1943, November 17. Philadelphia, Academy of Music. Chopin, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1950, January 5 & 6. Chicago Symphony Hall. Beethoven, Concerto No. 5. Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

1953, December 18 & 19. Academy of Music. Beethoven, Concerto No. 4. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1954, November 22. Academy of Music. Chopin, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1956, April 6 & 7, May 5. Academy of Music. Rachmaninoff, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1956, April 6 & 7, May 5. Academy of Music. Rachmaninoff, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1957, October 5, 8, 28 & 29. Academy of Music, Baltimore (8) Carnegie Hall (29). Brahms, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1959, March 23. Academy of Music. Tchaikovsky, Concerto No. 1. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1960, January 29 & 30, February 1 & 2. Academy of Music, Carnegie Hall (February 2). Beethoven, Concerto No. 4. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1960, August 25. Hollywood Bowl. Beethoven, Concerto No. 5. Los Angeles Philharmonic.

1961, April 5, 7 and 8, May 7. Academy of Music, Baltimore (April 5), Ann Arbor (May 7). Rachmaninoff, Concerto No. 2. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1962, August 18. Tanglewood. Tchaikovsky, Concerto No. 1. Boston Symphony Orchestra.

1964, January 30 & 31, February 1 & 3. Academy of Music. Beethoven, Concerto No. 5. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1964, April 13 & 15. Academy of Music, Carnegie Hall (15). Beethoven, Triple Concerto (with Stern and Rose). Philadelphia Orchestra.

1964, April 13 & 15. Academy of Music, Carnegie Hall (15). Beethoven, Triple Concerto (with Stern and Rose). Philadelphia Orchestra.

1966, January 24. Constitution Hall. Beethoven, Concerto No. 3. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1966 February 4 & 5. Academy of Music. Szymanowski, Symphonie Concertante; Beethoven, Concerto No. 3. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1966, April 11. Washington. Beethoven, Concerto No. 3. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1968, September 19, 20, 21, 24. Academy of Music, Carnegie Hall (24). Beethoven, Concerto No. 3. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1968, September 19, 20, 21, 24. Academy of Music, Carnegie Hall (24). Beethoven, Concerto No. 3. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1969, August 9. Saratoga. Beethoven, Concerto No. 5. Philadelphia Orchestra.

1970, July 30. Saratoga. Beethoven, Concerto No. 4, Triple Concerto (with Stern and Rose). Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1974, March 22, 23, 25 & 26,. Academy of Music, Washington (25). Schumann, Concerto. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1974, March 22, 23, 25 & 26,. Academy of Music, Washington (25). Schumann, Concerto. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1976, July 14. Hollywood Bowl. Beethoven, Triple Concerto (with Stern and Rose). Los Angeles Philharmonic.

1976, September 30, October 1, 2 & 5. Mozart, Concerto No. 24. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1980, August 7. Saratoga. Tchaikovsky, Concerto No. 1. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1980, August 7. Saratoga. Tchaikovsky, Concerto No. 1. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1980 September 25, 26, 27, 30. Academy of Music, Carnegie Hall (30). Tchaikovsky, Concerto No. 1. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

1983, May 17. Carnegie Hall. Beethoven, Concerto No. 5. Philadelphia Orchestra. Recorded concert.

Music

Schumann. Concerto in A minor Op. 54, the two last movements (Intermezzo: Andantino grazioso; Allegro vivace). Eugene Istomin. Philadelphia Orchestra. Live recording on March 1974.

.

Tchaikovsky, Concerto No. 1 in B flat major, Op. 23, first movement (Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso). Eugene Istomin, Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy. Recorded for Columbia on April 19, 1959

.

Ormandy rehearsing Brahms. A precious document filmed during a tour of the Philadelphia Orchestre in UK in the early 50s, which shows the simplicity and natural authority of Ormandy, as well as the fantastic dedication of all instrumentists.