HISTORY AND POLITICS

History and Politics, Introduction

History and politics were at the core of Istomin’s life. This chapter allows us to follow his evolution through the disruptions of the 20th century.

Eugene Istomin had an irrepressible need to know, to understand and, if possible, to act, both as a citizen and as an artist. Like Casals, he had chosen to be a man before being a musician, and many of his political decisions were detrimental to his career. He read extensively about political theories, from anarchism to neo-conservatism and Marxism. He had a strong inclination for debate, even with people who were far from his beliefs. He liked to play the devil’s advocate and defend theories opposed to his own, in order to put his interlocutor into a corner and oblige himself to think more deeply.

Communism and Nazism had built his attachment to democratic ideals, his mistrust of extremes and his rejection of totalitarianism. His convictions were progressive. He was revolted by injustice and poverty, and was counted amongst those artists who refused to play in halls where racial segregation still persisted. He advocated the right to education and the development of every human being. He belonged to the Kennedy generation, who believed that it was still possible to change the world. His commitment was so great that he decided to engage in politics for a while, refraining however from indulging in the idealism of many artists and intellectuals who believe that beautiful generous ideas are easy to implement.

Involvement in American politics

A devoted Democrat, he remained close to the highest echelons of government for many years. He had once played for President Truman, a music lover and pianist himself. After Eisenhower’s two terms, he supported Kennedy against Nixon and was won over by his charisma. Meeting Hubert Humphrey got him into politics for good. In 1968, in a difficult context, he became head of the Committee of Artists and Writers which supported Humphrey’s candidacy in the presidential elections. Humphrey planned to ask Istomin to become his cultural advisor, but he was narrowly overtaken by Nixon.

In 1972, Istomin could not approve of George McGovern’s proposals, which he considered too demagogic, and he withdrew definitively from political action. It was the only time he did not vote. Quite skeptical about Carter, with the exception of the Camp David Accords, which he welcomed, Istomin did not have any particular sympathy for Bill Clinton either: he admired his intelligence and determination, but regretted his populism in cultural matters.

Serving his country and fighting against communism

Istomin was both devoted to the country who had welcomed his parents (and where he was born) and determined to fight communism, which had forced his parents to flee their native Russia and perpetrated so many atrocities. He was convinced that in the Cold War, battles also had to be won in the field of cultural communication, especially through music, where no language barrier existed. He made himself available to the State Department, deploring the fact that the Soviet Union was so far ahead in this area. The United States used to send second-class soloists and ensembles abroad for cultural exchanges, while the USSR requisitioned its most distinguished musicians (Oistrakh, Gilels, Rostropovich, Richter). Not only was Istomin willing to offer his talent and time, but he convinced many prestigious colleagues to do the same. The Kennedy administration was highly interested, but the project was later neglected by Johnson.

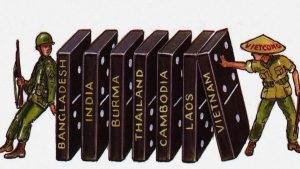

Istomin believed in the domino theory, which had been prevalent since Truman’s presidency. This theory stated that if a country fell under communist domination, neighboring countries would immediately be threatened and that soon all Southeast Asia would undergo the same fate. It was therefore necessary to intervene. This was the case in Korea, where it took no less than three years of hard fighting between UN troops (mostly American) and North Koreans (allied to the Chinese and helped by the Soviet Union) to stabilize the border between the two Koreas. When the American government decided to engage militarily, more and more massively, in Vietnam, Istomin considered it a legitimate decision. He thought that, like any war, it was a terrible thing, but that it was justified by the need to protect the free world. While many intellectuals and artists disagreed, Istomin declared his support and offered to travel to Saigon and give some concerts in 1966. His trip was a disaster – it was not even possible to play. Istomin soon realized that this war could not be won. He urged Humphrey, the Democratic candidate in the 1968 presidential elections, to distance himself from Johnson’s position and affirm his willingness to call for a cease fire and negotiate without preconditions. Under Nixon, the war continued for another five long years with the Americans, followed by two years without them. Finally, all of Vietnam fell into the hands of the communists, as did Laos and Cambodia.

Istomin never allowed himself to give in to naive optimism during periods of liberalization and truce. He was suspicious of the Strategic Arms Non-Proliferation Treaties (SALTs), warning that the Soviets should not be trusted and that it would be wise not to reduce the United States’ military budget by too much.

Due to his interest in Chinese civilization, Istomin was attentive to what was happening in China. He felt that the Cultural Revolution of 1966 was too brutal not to provoke a reverse reaction a few years later and that the balance of the world would be much more stable if the United States could break the unity of the communist bloc by opposing China and the Soviet Union. Without knowing that contacts were being secretly made by Kissinger, Istomin had taken steps to visit China in order to give concerts and master classes, believing that musicians should lead by example. Despite the support of Malraux, the Nixon administration did not allow him to do so.

Israel

Istomin repeatedly stated that he was ready to lay down his life for Israel. Traumatized by the Holocaust, he declined to play in Germany and Austria until the mid-1970s, and never felt completely comfortable there. This did not prevent him from thinking that Israel should resume contacts with these countries. He deeply admired the Jewish people for their courage, creativity, and love for music. He gave many concerts in Israel from his participation in the first edition of the Israel Festival in 1961. He also taught there and generously welcomed to America the talented young Israeli musicians he had discovered, like Yefim Bronfman, or those whom Stern had recommended to him (Pinchas Zukerman and Shlomo Mintz).

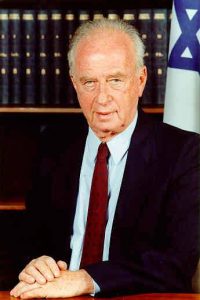

Istomin was very friendly with the great leaders of the Israeli Labour Party (Meir, Ben-Gurion, Kolleck) and favored the idea of a secular state. Although he demonstrated his unwavering support when Israel was attacked by its neighbors, he was nevertheless convinced that Peace would come only if a hand were extended to the Arabs. The assassination of Rabin, to whom he was very close, left him in despair.

France

Apart from the African continent, there were few countries in which Istomin did not perform! Happy to travel, curious about everything and especially about people, he used to say that his country was “wherever there is a piano.” Although he considered himself a citizen of the world, there was still one country which was especially dear to his heart: France. It was the first foreign country he discovered in 1948, and to which he remained attached and deeply in love with its language and way of life. It was an idealized France, the France of the Enlightenment and of the Declaration of Human Rights. In 2000, Istomin was made Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur by his friend and former Director of the French Radio and Television Arthur Conte, thanks to his involvement in French musical life.

The years of disillusionment

The years 1966 to 1968 were for Istomin both the peak of his political commitment and the beginning of his disenchantment. At first he realized with bitter certitude that winning the Vietnam War would be impossible. Later on, he became aware of the uncontrollable and harmful nature of the CIA, who had manipulated information in Vietnam and plotted the fascist coup in Greece. And finally, Humphrey, for whom he had expended so much energy, had been overtaken by Nixon who, in Istomin’s mind, was the very example of incompetence and dishonesty.

His natural optimism gradually gave way to a more pessimistic realism. Istomin had been very impressed by Toynbee and his vision of the history of civilizations. A civilization can live and develop only as long as there is a challenge – otherwise, it ends up decaying and killing itself. The example of Greece had particularly struck Istomin, who had come to wonder whether the same phenomenon was not happening to the Western civilization. This led him to question the functioning of democracies. There was no longer any real collective ideal and demand. The main human motivations had become money, power and comfort.

The elections of Reagan and Bush and the evolution of American politics and society further undermined his optimism and even caused him to seriously consider leaving the United States on several occasions to settle in Europe, as his friend Pierre Salinger had done in Provence, but he was aware that Europe was also taking the same path.

The role of culture in the crisis of Western civilization

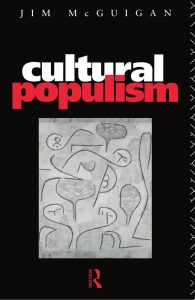

Wasn’t cultural egalitarianism an aberration that led humanity to mediocrity? Many people regarded everything as culture, and thought that all cultures were equal: Elvis Presley was as great as Mozart, and Pop Art was equal to Rubens.

Wasn’t cultural egalitarianism an aberration that led humanity to mediocrity? Many people regarded everything as culture, and thought that all cultures were equal: Elvis Presley was as great as Mozart, and Pop Art was equal to Rubens.

For Istomin, it was clear that we were forgetting the essence of democracy. It not only meant freedom and equality of rights among citizens, but it was also each person’s duty to raise his own intellectual and moral awareness to as high a level as possible. Elitism, in its original sense, must be a natural principle of democracy. However, as a result of the combined effect of the market law and the demagogy or incompetence of the governments, cultural life and media are gradually losing their ambition. The citizen indulges guilt-free in the easy way without scruples: why make the effort to enter the universe of Mahler or Boulez when jazz or pop music pieces offer us instant pleasure? All the more so if you have been led to believe that they are only equivalent forms of the same art.

In his interview with Patrick Ferla, Istomin said that he enjoyed jazz and loved Frank Sinatra’s songs, but he placed these forms of music in their proper context: “All great music is a challenge for the human being. A Schubert symphony, for example, arouses a wide range of thoughts and emotions. The Rite of Spring too, even if they are completely different thoughts and emotions. Both stir up the attention and the consciousness of those who listen to them. Popular music is not a challenge to the consciousness, it is rather a kind of calming, a kind of release, something nostalgic, something sexual. We sing ”Oh ! Baby !” and get into a sensual rhythm. It’s something simple, pleasant, but it doesn’t go any further than that. While a Nocturne or an Etude by Chopin is not just about the atmosphere, there is something that goes into a higher dimension of the intellectual and sensitive experience. It pushes us, it requires more of us. To enter the world of this art, it is certainly not necessary to become an expert, but it is an experience that we cannot forget, that we will want to repeat and deepen. When we become aware of what great music is, we will never put it on the same level as popular music.” Istomin felt a tremendous frustration at the misuse we make of our freedom in terms of culture: “The people want shit, so let’s give it to them! What else can we do if we are in a democracy…?’’ For Istomin, this invasion of mediocrity was evidence that our civilization was in trouble. The world cannot do well without the influence of culture at all levels of society.

Although Istomin had abandoned the idea of direct political activity in the early 1970s, he kept an eye out for the developments of the world, and was always ready to commit himself, as an artist and as a citizen, for supporting all the causes in which he believed. Where he felt most useful and happy was on his major tours across the United States, travelling with his own pianos in a truck, in the late 1980s and early 1990s. He brought music to places deserted by the usual concert circuit, with the feeling that music should not be reserved for the rich people of the big cities. He had lost some of his Beethovenian sense of optimism, (which expects that good will and justice would always triumph) but his ideal had remained intact.