Eugene Istomin was immersed in Russian culture during his childhood until he left Siloti. He spoke Russian before speaking English. His parents spoke Russian at home and endlessly practiced the folk songs they were performing at the famous cabaret The Bat. His parents’ friends were mainly Russian immigrants. The family of his first teacher, Alexander Siloti, was his second family for more than six years, and they spoke more Russian and French than English. However, Istomin had great difficulty in assuming his Russian roots.

Russian music and musicians

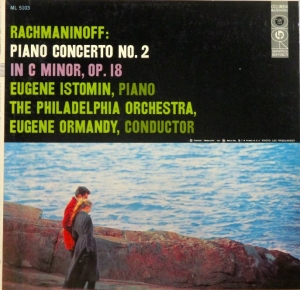

All the young pianists of Istomin’s generation (Kapell, Graffman, Janis, Katchen, and even Fleisher) built their careers more or less on the concertos by Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky and Khachaturian. During the 1940s and 1950s, this repertoire was the most effective path to success. Istomin, however, refused, playing the Rachmaninoff Third Concerto only once in 1944. Despite the rapturous reception of the public and the critics, he abandoned it forever. David Oppenheim had to insist quite strongly before Istomin agreed to tackle the Rachmaninoff Second and the Tchaikovsky First and record them for Columbia (in 1956 and 1959). Despite this, he rarely played them in concert, dropping them from his repertoire as early as 1963. Much later in his career, he turned again to the Russian composers, this time not to perform blockbusters but in order to champion works which he considered unjustly neglected: the Variations on a Theme by Chopin (which he ultimately renounced playing in public) and the Fourth Concerto by Rachmaninoff, and the Medtner Sonata in G minor Opus 22.

All the young pianists of Istomin’s generation (Kapell, Graffman, Janis, Katchen, and even Fleisher) built their careers more or less on the concertos by Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky and Khachaturian. During the 1940s and 1950s, this repertoire was the most effective path to success. Istomin, however, refused, playing the Rachmaninoff Third Concerto only once in 1944. Despite the rapturous reception of the public and the critics, he abandoned it forever. David Oppenheim had to insist quite strongly before Istomin agreed to tackle the Rachmaninoff Second and the Tchaikovsky First and record them for Columbia (in 1956 and 1959). Despite this, he rarely played them in concert, dropping them from his repertoire as early as 1963. Much later in his career, he turned again to the Russian composers, this time not to perform blockbusters but in order to champion works which he considered unjustly neglected: the Variations on a Theme by Chopin (which he ultimately renounced playing in public) and the Fourth Concerto by Rachmaninoff, and the Medtner Sonata in G minor Opus 22.

What Istomin had also absolutely refused to do was to be billed as a Russian pianist. For many years, this had been a very promising argument in the United States. Olga Samaroff, the eminent American pianist, was born in Texas, but her real name was Lucy Mary Olga Agnes Hickenlooper. With the help of her Russian pseudonym, she began a very successful career in 1905, which she had to interrupt in 1925 due to an unfortunate fall. She was the first performer after Hans von Bülow to play the Beethoven 32 Sonatas in concert, and her prestige was such that she was able to install Leopold Stokowski, her husband, as music director of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Russian performers often received a frenzied welcome during their tours in the United States: Oistrakh and Gilels in 1955, Rostropovich in 1956, the Bolshoi Ballet in 1959, Richter in 1960. These tours were organized by Sol Hurok, the great American impresario of Russian origin, who had exclusive connections with the Soviet authorities.

Hurok had been interested in Istomin ever since his success at the Leventritt Competition and his debut with the New York Philharmonic. He promised to establish him as a star, intending to capitalize on the young pianist’s Russian origins. Hurok had no hesitation in introducing Serkin on his first American tour in 1936-37 as a “sensational Russian pianist”! Istomin, however, did not wish to be labelled with this image. He turned down Hurok’s proposal, and on Serkin’s advice chose the other great American manager, Arthur Judson.

However, Istomin eventually joined Hurok in 1962, at Isaac Stern’s request, when the rise of the Trio made it preferable for its three members to have the same manager. Under the aegis of the State Department, Sol Hurok organized Istomin’s one and only tour of the USSR in 1965.

Russian language and literature

Istomin liked reading in Russian but felt that he had not mastered the language well enough to fully appreciate the great literary works. The Russians with whom he spoke were surprised at his fluency, but he himself thought he spoke too basic a Russian and was not satisfied with it. Moreover, he had very few opportunities to speak Russian, apart from his conversations with Slava Rostropovich.

His library included many books by Russian authors, most of them in English translation, with a marked preference for Tolstoy. In addition to his main novels, Istomin had collected no less than five biographies and the complete edition of his correspondence. In October 1948, he participated in a major concert given at Carnegie Hall in tribute to Leo Tolstoy on the occasion of the 120th anniversary of his birth, for the benefit of European immigrants in difficulty.

History and politics

It was through the stories of his parents and their Russian immigrant friends that Istomin, at a very young age, learned of the Soviet Revolution tragedies. His mother had seen her first husband shot before her eyes. His father, an officer of the Tsar’s Air Force, had participated in the battles against the Bolsheviks, and after the final defeat in Crimea, reached Constantinople, where he soon left for America. He left behind a wife and son, whom he would never see again.

Very early on, Istomin followed the important events in the USSR with his father, especially the Moscow Trials between 1936 and 1938, which allowed Stalin to eliminate all his opponents. Among them were soldiers who had been his father’s comrades and had chosen the Bolshevik camp. They were all sentenced to death.

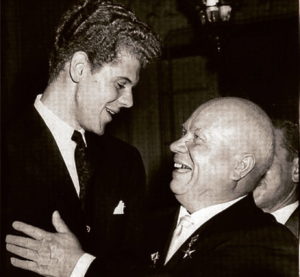

Istomin always paid a great deal of attention to what was happening in the Soviet Union: the pact with Nazi Germany in 1939, the domination of Eastern Europe after WWII, the crushing of the Budapest insurrection in 1956, the accession of Khrushchev and de-Stalinization… Upset that his country was abandoning the field of cultural communication to the Soviet Union, Istomin offered his services to the American government to give concerts wherever this would enhance the image of the United States. He was thus offered several missions on the other side of the Iron Curtain in 1963 and 1965.

The USSR tour of April 1965

When the tour was concluded, Nikita Khrushchev was the head of the USSR, but he was overthrown and replaced by Brezhnev in October 1964. After a period of relative freedom, the cultural sector was once again put under strict control. Nevertheless, Istomin’s reception by the Soviet authorities was less glacial than the one he received in Sofia two years earlier, and was at least more respectful.

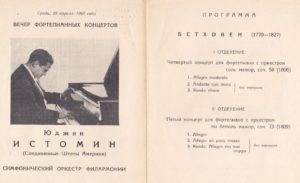

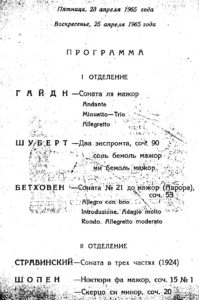

Within about three weeks, Istomin gave nearly ten concerts in Moscow, Kiev, Riga and Leningrad. In Kiev, he played with the State Symphony Orchestra of the Socialist Republic of Ukraine and its music director Stepan Tourtchak (the Beethoven Fourth Concerto and the Brahms Second). The final two concerts involved the most prestigious orchestra in the USSR, the Leningrad Philharmonic, conducted by Arvïds Jansons. This time, Istomin performed the Beethoven Fourth and Fifth. For his recitals, he had kept the program he regularly proposed at that time: Haydn, Sonata in A Major Hob.XVI:12; Schubert, Impromptus Op. 90 No. 3 and 2; Beethoven, Sonata No. 21 “Waldstein”; Stravinsky, Sonata; Chopin, Nocturne Op. 15 No. 1 and Scherzo No. 1 Op.20.

He did not want to play any Russian music, except for the Stravinsky Sonata, which has nothing Russian about it! Indeed, it was out of the question for him to act as the prodigal child back in the country of his ancestors. He was an American pianist, a specialist in the classical and romantic repertoire – no more and no less. Istomin was quite happy with the way he had played and the warm reception he got from the audiences. He received many messages of admiration and thanks in both Russian and English, which he kept. Most of them were anonymous, with the exception of a very touching letter, signed by four students from the Minsk Conservatory, telling him that no other pianist had ever moved them so much and begging him to come again.

Istomin had been able to meet members of his family, in particular his father’s first wife, who told him that his half-brother had been killed during the Second World War.

A deeply entrenched anti-communism

In an interview on Radio Suisse-Romande in 1989, Istomin said about the Russian Revolution: “It is perhaps the greatest catastrophe of all time, at least one of the greatest disappointments in history, for everyone, but especially for intellectuals. After the Revolution, almost everyone believed in it, it had become like a religion! And look at it today! I toured in 1965, and came back in 1980. I don’t want to talk about politics, I’m not a politician. And I have never been tempted by orthodoxies, whether religious or political. I was not attracted to Marxism, but many of my generation, all intellectuals, were very tempted to have faith in it, with the dramas and disappointments that we know. Prominent writers, Sartre, Hemingway, have commented much better on this subject than I could.’’

Convinced of the evil nature of the communist regime and its boundless imperialism, Istomin had long approved of American military interventions in Southeast Asia before he realized that these wars were impossible to win, and he deeply challenged Johnson’s strategy and the uncontrollable role of the CIA from 1967 onwards.

Istomin was very skeptical about Gorbachev’s accession in the spring of 1985 and the promises of liberalization. When asked in January 1989 by Patrick Ferla about the evolution of the Soviet Union, he cautiously replied: “I certainly hope that Gorbachev will succeed. I think he is aware that he is on an almost hopeless path, but if he is allowed to continue, we can hope that some things will change. I fear that the system itself will not provide sufficient freedom for the economy to evolve, and for the development of the human being to be possible. I’m talking about the ordinary man, the man in the street. But there is also the possibility that it could lead us to a kind of ambush. The free world must remain on the defensive.’’ .

Istomin’s participation in the Budapest Cultural Forum in 1985 reinforced his conviction that communist regimes were not likely to become more liberal. This impressive gathering of artists, writers and musicians was intended to lay the foundations for constructive cultural cooperation between all the countries that had signed the Helsinki Accords, but it ended in the greatest confusion, with the USSR accusing the USA of every possible evil, just as they used to do during the good old days of the Cold War.

The dramatic conflicts in the former Yugoslavia had also reinforced his feeling that the legacy of communism would be terribly difficult to wipe out, both in the structures of states and in the minds of their citizens. After Gorbachev was ousted, the seizure of power by Boris Yeltsin and Putin left Istomin even more perplexed. He suspected that Putin would keep the darkest aspects of communism and add those of tsarism.

About Russian soul

For Mstislav Rostropovich, there was not a shadow of doubt that his friend Eugene Istomin had kept his Russian soul. He chastised him for not having more Russian works in his repertoire and for not agreeing to learn Tchaikovsky’s Trio and play it with him! He was also surprised that Istomin was not eager to reconnect with Russia, whereas he himself dreamed of returning and wanted to die there. The big difference was that Rostropovich was born in Baku and had spent the first 47 years of his life in the Soviet Union, whereas Istomin had spent only a few weeks on tour there in 1965. The project of HBJ to publish a large-scale series of books on the collections of the Hermitage Museum of St. Petersburg (still named Leningrad) might have enabled Istomin to reconnect with eternal Russia. He had successfully completed the difficult negotiations with the Soviet authorities and the Museum’s curators, but the invasion of Afghanistan by Soviet troops brought this exciting project to a sudden end.

In fact, for Istomin, the Russian soul no longer existed in reality and it was very doubtful that it would ever be reborn. It only survived in his childhood memories: Alexander Siloti (to whom he paid tribute in 1990, organizing a concert that funded a scholarship in his name at the Juilliard School), and the circle of Russian immigrants along with his parents, who had given him support in difficult times. These days, the Russian soul could only be found in the literature and music of the past. Istomin admired Stravinsky and identified with Sergei Rachmaninoff, particularly with his Fourth Concerto, which combined Russian sensibility and American culture – a mixture that went straight to his heart.

Music

Stravinsky. Sonata (1924), second and third movements. Eugene Istomin. Recorded in 1966 and 1967 for Columbia, and issued in 2015 by Sony. This was the only “Russian” music that Istomin agreed to play during his tour in the Soviet Union in 1965.

Audio Player