Among the many tributes Eugene Istomin received on his 75th birthday celebration, several referred to his passion for literature. The Librarian of Congress, James Billington, wrote: “He is a modern humanist with a library that includes the elegant prose of the late Victorian, the great French and Russian epic novels, Homer and Plato, Kierkegaard and Freud, Mark Twain and Erle Stanley Gardner”. Henry Raymont noted: “Remarkably, you have never confined your attention to music. You are a voracious reader with a refined taste for contemporary literature and art. Wendy and I will never forget the evening you dazzled our daughter Sarah, a budding writer, with your keen knowledge of the works of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound and Paul Bowles, and your collection of letters and first editions”.

For Istomin, reading was a source of inexhaustible pleasure. It was an effective antidote for his frequent insomnia, exacerbated by jet lag. One could not help wondering if he really tried to sleep, or if he was mainly looking for an excuse to pursue his reading without interruption!

An unlimited curiosity

In his reading, the desire to discover new horizons coexisted with a will to delve as deeply as he could into the work of some writers or in domains with which he was already familiar. He had the same attitude in Music and Art. Istomin developed a particular interest in authors whose personality and ideas were different from his, and even in those who were in conflict with his ideals. He needed to understand the “other one”, the person who did not think and act like him. His greatest fascination was for two writers of whose ideas he disapproved: Ezra Pound and Louis-Ferdinand Céline. This fascination was so intense that his library included about one hundred and fifty books by and about Pound, including many rarities and limited editions!

Reading was a way for him to get to know humanity, the world, and God. His permanently-awakened curiosity was directed towards a variety of interests. Poetry in English and French occupied an important place. Although he was attentive to contemporary literature (with a special fondness for Milan Kundera), he constantly returned to his best-loved writers – Flaubert, Proust, and above all Montaigne, who brought him egotism, inner freedom, tolerance, open-minded skepticism, and the cult of friendship and loyalty.

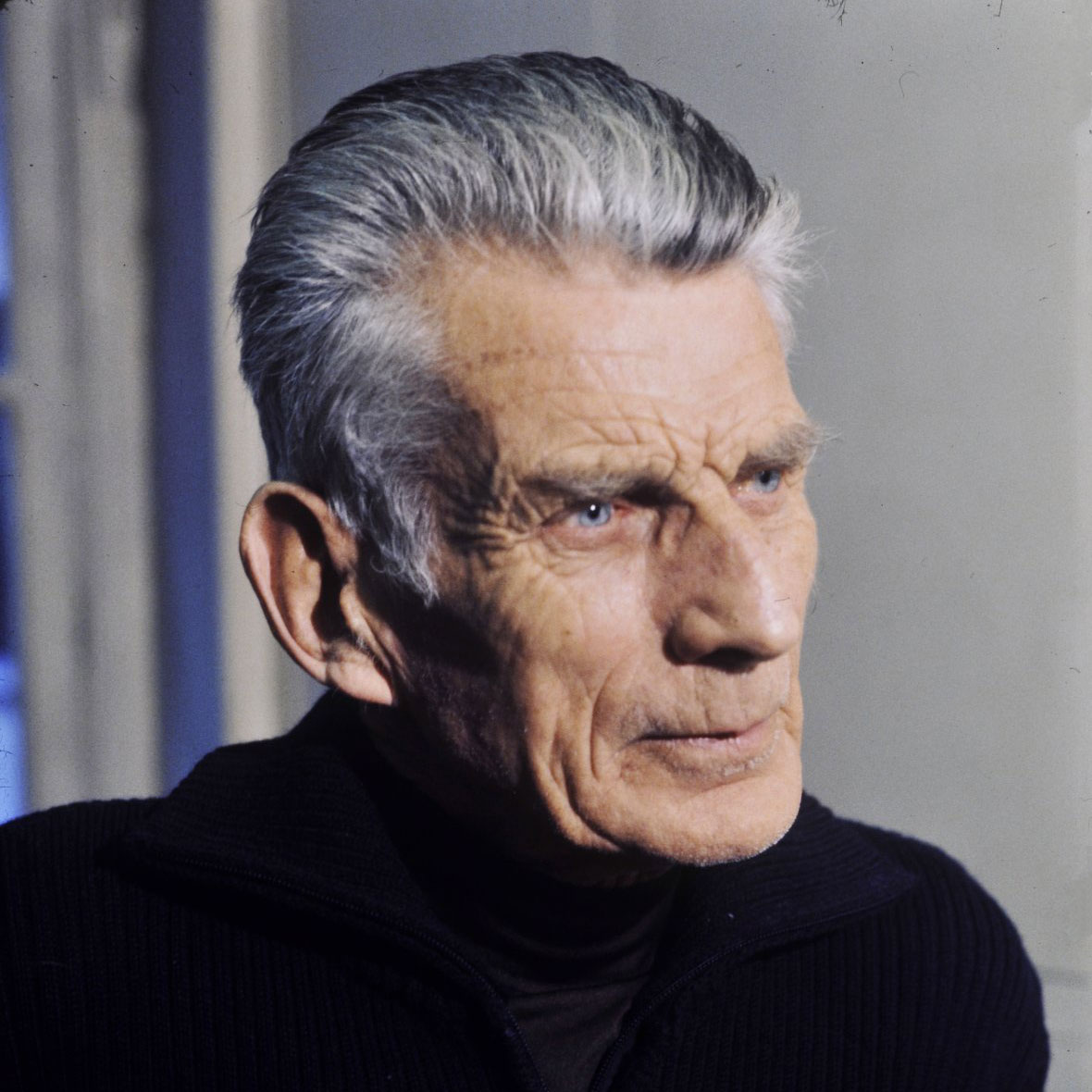

Strangely enough, Istomin was not tempted to enter in personal contact with writers, unlike painters. The only exception was Samuel Beckett, to whom he was introduced by his close friend Avigdor Arikha. Nevertheless, Istomin’s affection and admiration for Beckett were more for the person than for the writer who, in any case, was very secretive about his work.

Philosophy and science made up a significant part of Istomin’s reading. He had no scientific education, but had always been fascinated by mathematical and physical theories. Ned Rorem remembered him already being immersed in the Principia Mathematica by Whitehead and Russell when he was still a teenager. Later, he embarked on treatises on nuclear physics or astronomy, and read them as if they were poetic evocations of the origin of the world. In Istomin, there was always a confrontation between the temptation of nihilism and the aspiration for the existence of a divine presence.

His Library

Istomin’s library reflected the tremendous diversity of his readings. It included more than eight thousand volumes. The University of Maryland, to whom he bequeathed the collection, estimated its value at more than three million dollars. It contained nearly a thousand first editions, facsimile editions or manuscripts.

Istomin’s library reflected the tremendous diversity of his readings. It included more than eight thousand volumes. The University of Maryland, to whom he bequeathed the collection, estimated its value at more than three million dollars. It contained nearly a thousand first editions, facsimile editions or manuscripts.

Istomin needed to live among his books and his works of art. He was a true bibliophile. He delighted in visiting a bookshop, in buying and possessing a book, even in touching the binding and the paper. Original editions were invaluable to him, books with a rich history, which had been passed on with loving care from hand to hand over time. One of his greatest satisfactions as a book lover was his role as special advisor to William Jovanovich, the president of HBJ. Among other projects, he supervised the facsimile reprinting of some original historical editions, including the complete works of Joseph Conrad and Thomas Hardy.

The love for languages

The quality of linguistic style was an essential component of pleasure for Istomin, regardless of the language. English and American literature held first place for him, followed closely by French literature. Russian was his native language, which he spoke before he learned English. The Russian people with whom he talked were often surprised and even amazed, by his ease and finesse. He also liked to read Russian literature, but felt he had not mastered the language well enough to be able to make the most of its great prose and poetry. His knowledge of Italian (assimilated during his many tours in this country) and of Greek (a language he began to learn and which he would have loved to master) was not sufficient to allow him to read Dante and Plato in their original language. This was frustrating for him, even though he possessed several translations of their works.

Istomin also had a remarkable ability for writing, always managing to find the right tone, formula, or word. The self-interview entitled The World Series Sonata which he wrote in 1977 is a gem of style and humor. It was published by the New York Times and various newspapers in the States in October 1977, and can be read in its entirety on this website. Marta often relied on his expertise for the most delicate texts she had to write when she managed the Kennedy Center and the Manhattan School of Music. He was also capable of doing this in French, as he demonstrated by writing his own acceptance speech when he was awarded the Légion d’Honneur.

This love for languages also led him to learn slang, and to take an interest in particular expressions which were used only in certain regions, for example in the southern states of America.

Epilogue

When he became weakened by illness and was no longer able to read for long periods of time, Istomin listened to the complete recordings of a few great books. He particularly enjoyed hearing Flaubert’s Education sentimentale and his beloved Essais by Montaigne. Despite the span of three centuries, they were two uncompromising looks at the human condition, with a clear and elegant style which went directly to the essentials. The ideal of Istomin’s entire life!