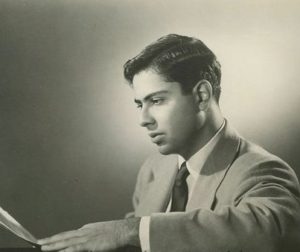

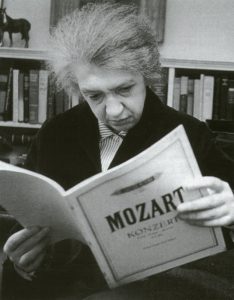

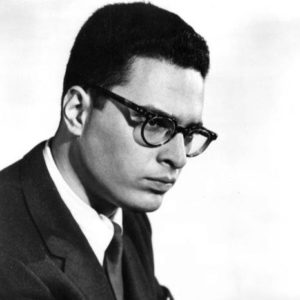

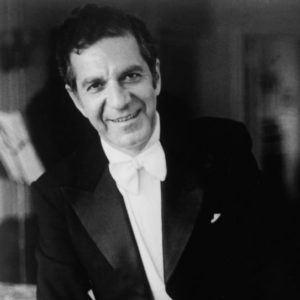

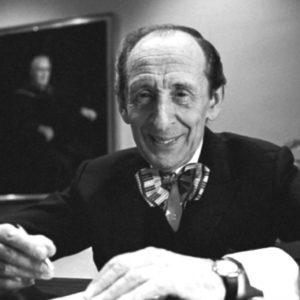

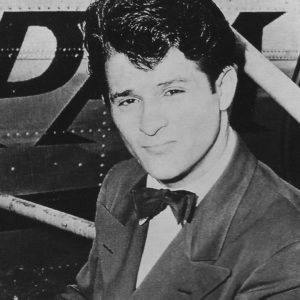

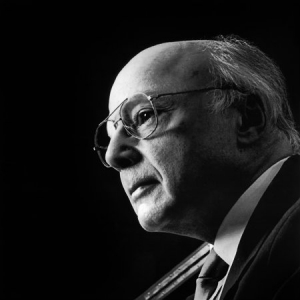

Eugene Istomin belonged to an extraordinary generation of pianists who were born in America from the early 20s to the mid-30s : William Kapell (1922), Eugene Istomin (1925), Julius Katchen (1926), Seymour Lipkin (1927), Leon Fleisher , Gary Graffmann, Jacob Lateiner and Byron Janis (1928), Charles Rosen (1930), John Browning (1933), and Van Cliburn (1935).

To what can we attribute such an explosion of talent, when there had been no American pianist of great fame since Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869)? The main reason was due to the emigration caused by the Russian Revolution and subsequently, to the rise of Nazism. It brought outstanding pianists to America (Rachmaninoff, Horowitz, Schnabel, Serkin…) who served as role models and teachers. American orchestras benefited from the arrival of great European conductors like Toscanini, Walter, Szell, Ormandy, Reiner, and Koussevitzky. Emigration had also brought many Russian and Jewish families who were interested in classical music. They were potential listeners and ensured that their children received a serious musical education. All these factors contributed intensively to the spectacular development of musical life in America.

In December 1957, Time Magazine reported this situation in a paragraph entitled Artistic Holdup: “Pianists Graffman, Istomin and Fleisher currently stand together on a musical plateau, well above most of their contemporaries and within climbing distance in another 15 or 20 years of the eminence occupied by the Rubinsteins and Horowitzes. In artistic maturity, they are probably farther advanced than these looming figures were at their age. ‘We were a very lucky generation,” says Istomin. “During the war, so many of the great musicians came to the States. When I heard men like Rubinstein, Artur Schnabel, Horowitz or Bruno Walter, I felt as though artistically I had robbed the National City Bank of New York.”

Strangely enough, competitive spirit, which seems quite inevitable in such an environment, was avoided by all these young pianists. They felt their main purpose was their own musical achievement and thought that there was room for everybody in the musical world. It was natural to help each other, listening to and criticizing one another, as well as sharing their doubts, discoveries and supports. According to Fleisher, Istomin “encouraged all of us to grow and opened doors that would have otherwise been closed”. Thus was born an association which reminds one irresistibly of Schumann’s Davidsbündler: the OYAPs (Outstanding Young American Pianists). In addition to Istomin, its mainstays were William Kapell, Leon Fleisher and Gary Graffman, with whom his relationships were warmly fraternal.

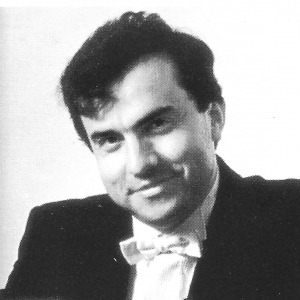

The attention and affection he gave to his colleagues went far beyond this small circle, as John Browning attested: « Eugene is, along with his tremendous gifts, an extraordinarily thoughtful friend and colleague. He always concerns himself with the welfare of others – their needs and problems – and he is always searching for ways to improve the status of the musician and the music world.”

This solicitude was not limited to his contemporaries and friends. In 1956, he arranged Clara Haskil’s entire tour in the United States, taking care of everything (engagements, travel arrangements, concert pianos), leaving his apartment at her disposal, showing her New York and introducing her to his musician friends. He was always willing to support young musicians by giving them advice and helping them to obtain engagements. Among them were Pommier, Tocco, Zukerman, Ax and Bronfman.

Beyond his genuine generosity and friendship, which made him quite impervious to envy, Istomin worried only about his own demand for perfection. Claude Frank spelt it out for James Gollin: “However good a performance was, Eugene should have played better… For a good reason, because his comparison was not with other pianists, it was with God.”

This fantastic generation, which promised to be so successful, was ultimately marked by a dark destiny. Some of them died tragically at an early age: William Kapell at 31 in a plane crash; Julius Katchen at 43 from cancer. There were dramatic disabilities: for Leon Fleisher and Gary Graffman, paralysis of the right hand, or in Byron Janis’ case, arthritis. There was Van Cliburn’s burnout. The careers of several brilliant pianists (Jacob Lateiner, Seymour Lipkin, John Browning, Claude Frank) were sacrificed on the altar of marketing. The number of their concerts slowly but inexorably decreased, while they were at the peak of their artistry, because American managers were eager to present new names from Europe or other continents.

Within this group, Istomin held a unique place. He managed to miraculously escape serious injuries and never interrupted his career, despite undergoing surgery seven times. He had been wise enough to leave behind the finger-breaking concertos by Rachmaninoff and Tchaïkovsky early on. He escaped burnout by nurturing his mind with other passions besides music. His career did suffer from the death or retirement of the great conductors who supported him (Szell, Reiner, Munch and Paray) as well as from his clash with Columbia Records, but he continued to perform extensively until the mid-90s. The only frustration he had to overcome was that his concerts with major orchestras or in most prestigious venues gradually decreased, but as Emanuel Ax concludes: “His artistry and words of wisdom are parts of the life of so many of his colleagues, and he will always remain in the annals of the great pianists”.

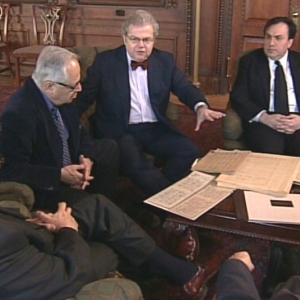

This chapter is a broad overview of the fruitful relationships Istomin established with all the pianists he had met, and who had been his teachers, his role models, friends, colleagues, or his disciples. In addition, there is the story of the OYAPs and an account of the exciting Great Conversations in Music chaired by Eugene Istomin at the Library of Congress and for which he had gathered a dream team of pianists: Emanuel Ax, Yefim Bronfman, Leon Fleisher, Gary Graffman, and Charles Rosen.