PERFORMING

During his career of nearly sixty years, Eugene Istomin gave more than four thousand concerts. Despite the stage fright that invaded him each time, playing concerts always remained at the center of his career and life: “Piano music is best performed and heard in the context for which it was written – the concert hall. Studio recordings, for all their virtues, don’t capture the sweat, the soul of music-making.”

“Before each concert, I say to myself that this may be the last time I’ll ever play. I may die. As the days and years go by, it becomes more and more true and I gain greater tranquility within myself.” Istomin often let himself be drawn into huge tours and a whirlwind of concert activity. The more often he played, the less nervous he was. The worst ordeal for him was to resume performing after a period of inactivity, so he had long since abandoned taking a holiday or even the shortest of sabbaticals. At the end of the 1950s, he was giving nearly 120 concerts a year.

A deliberately limited repertoire

It was not only from a desire to play only works in which he felt he had something truly personal to say that Istomin limited his repertoire in concerto and recital. It is also because of his need for perfection and the habit he had of playing often in public from an early age. He had started his career “the old-fashioned way”, touring extensively with Busch, where he alternated playing three concertos throughout the tour of nearly fifty concerts. He quickly embarked on long tours, and remained accustomed to building his programs around the main pillars of his repertoire, making minimal changes to them over the course of a season and only adding or removing a few pieces, according to the organizers’ requests or political needs (he always played works by contemporary American composers when he was on an official tour sponsored by the State Department).

It was not only from a desire to play only works in which he felt he had something truly personal to say that Istomin limited his repertoire in concerto and recital. It is also because of his need for perfection and the habit he had of playing often in public from an early age. He had started his career “the old-fashioned way”, touring extensively with Busch, where he alternated playing three concertos throughout the tour of nearly fifty concerts. He quickly embarked on long tours, and remained accustomed to building his programs around the main pillars of his repertoire, making minimal changes to them over the course of a season and only adding or removing a few pieces, according to the organizers’ requests or political needs (he always played works by contemporary American composers when he was on an official tour sponsored by the State Department).

This permanence of the same works in his concerts naturally gave him a feeling of security. He had less to fear from memory lapses or treacherous spots in recently learned or rarely performed works. This allowed him to give free rein to his inspiration and to devote himself solely to music, as long as the instrument did not perturb him. In the last part of his career, he managed this by playing as often as possible on his own pianos, as Horowitz and Serkin used to do. On the other hand, he categorically rejected the idea of playing a recital – for him the most difficult but also the most accomplished and exciting form of a pianist’s activity – with the score, and was shocked to hear that Richter was doing so.

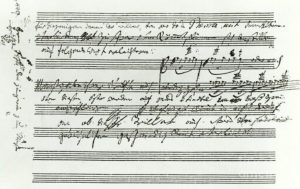

Beethoven’s notes of advice for performers of the Waldstein Sonata, a work which Istomin played in concert at least 500 times!

This limitation of the repertoire could, however, have led to a feeling of lassitude, but Istomin did not think so: “Every professional has to face the problem of boredom if he plays the same piece over and over. I really believe that I play a concerto better the seventh or eighth time in one season than the first.” Istomin never had the feeling of a routine, continually deepening his understanding and always discovering something new. In an interview with Bruce Duffie, John Browning reported on an observation from Serkin: “I have been playing this piece for forty years and it is only now that I see where the top of the phrase is! And you think, ‘How deaf can you get?’ I think things get easier when you become less self-centered. This brings us directly to the message.” A feeling which Istomin would certainly have shared.

It is nevertheless true that this limited repertoire was detrimental to his career. His recital program was not renewed often enough to encourage the organizers to invite him again. As for his choice of concertos, he either offered some of the most famous ones, or works that no orchestra wanted (Kirchner, Szymanowski, Rachmaninoff 4).

A musician is not an actor!

In a 1968 interview with John Garabedian, Eugene Istomin said: “A pianist must be an actor, an architect, an acrobat, a preacher, and a poet.” However, he gradually renounced the term actor, or at least considered himself to be a narrator who would only use his voice. The message had to emerge only from the music itself.

At the beginning of his career, Istomin’s playing was quite spectacular, as can be seen in the film of the Schumann Concerto at the Casals Festival in Puerto Rico in 1959. There were no histrionics in his attitude, but his face was expressive and the gestures very communicative. Over the years, he would tend towards even greater soberness. His ideal had become Rachmaninoff’s austerity: “His face looked like a Buddhist mask. At the keyboard, he didn’t move. I remember his playing, how he looked when he did that”. “He was still absolutely impassive, like Jascha Heifetz. The fire, the terrific passion came from the sound and not from his face! It was all happening under the surface. Nowadays players visibly show how they feel, Rachmaninoff would be horrified.”

This refusal of demonstrative playing and the desire to be entirely devoted to pure musical expression was particularly noticeable from the 1970s onwards. All the Chicago critics were struck by this at his May 1971 recital. Thomas Willis stated in the Chicago Tribune that Istomin was “a welcome antidote to the histrionics that affect so many of the fire and brimstone technicians who surround him.” In an interview with Robert Jacobson, he describes himself as an heir to the virtuosos of the nineteenth century: “Basically, my feelings about music are what are described as romantic. I’m an intellectual, not an exhibitionist in the superficial sense of the word… For me, the glamour and patina are in the actual making of the music, not in the appearances. In that sense, I think that I like to practice this deception, because what I do musically is intended to be extremely dramatic, emotional, involved and passionate – yet the exterior I like to give is that the person playing is simply a vessel for this thing to happen, not an actor. The acting is taking place through the notes.”

The refusal of easy success

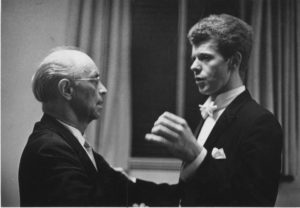

Serkin’s greatest fear was that Istomin would be ruined by success! This concern was all the greater because success had come very early and the risk could not be ignored. Winning two prestigious competitions in a row, and making his debut first with the Philadelphia Orchestra and then with the New York Philharmonic in the same week would have been enough to turn anyone’s head.

If Serkin was often right in thinking that his student was not working enough, he was wrong in imagining that applause would sway his musical ambition. On the contrary, even the opposite happened. When Istomin played the Rachmaninoff Third Concerto for Serkin, his teacher complimented him (which rarely happened) and encouraged him to perform it in concert. Istomin played it with great success in Chicago in 1944, but immediately abandoned it. He intended to devote himself primarily to the greatest composers: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, Chopin and Brahms.

Even before his twentieth birthday, Istomin, who asserted that he was a musical libertine in his youthful years, had adopted his teacher’s Jansenism in terms of repertoire. When by chance he attacked a bravura piece, such as Chopin’s Polonaise “Héroïque”, he exalted its dramatic tension rather than its virtuosity, even depriving his public of fireworks.

This reluctance to succeed went much further than the rejection of gratuitous virtuosity or a demonstrative style at the keyboard. He realized very early on in his early childhood that playing the piano attracted attention, affection and admiration. It could very quickly become an exercise of seduction, fascinating indeed, but at the same time dangerous and potentially immoral. He decided to devote himself first and foremost to his musical ideal rather than to conquering the public, telling Robert Jacobson: “I don’t seek, or I no longer seek to be loved.” When John Gruen asked him in 1971 why he was not considered more as a star, he replied: “Wild public popularity… this is something I am very dubious about. I haven’t courted it in the early stage of my public life. I think you have to want to be wildly loved and wildly applauded. You have to do things to make this happen. I’ve always been repelled by that from the very start, because my tendency was always to get to the substance rather than to the appearance of music.”

This reluctance to succeed went much further than the rejection of gratuitous virtuosity or a demonstrative style at the keyboard. He realized very early on in his early childhood that playing the piano attracted attention, affection and admiration. It could very quickly become an exercise of seduction, fascinating indeed, but at the same time dangerous and potentially immoral. He decided to devote himself first and foremost to his musical ideal rather than to conquering the public, telling Robert Jacobson: “I don’t seek, or I no longer seek to be loved.” When John Gruen asked him in 1971 why he was not considered more as a star, he replied: “Wild public popularity… this is something I am very dubious about. I haven’t courted it in the early stage of my public life. I think you have to want to be wildly loved and wildly applauded. You have to do things to make this happen. I’ve always been repelled by that from the very start, because my tendency was always to get to the substance rather than to the appearance of music.”

Istomin knew what he would have to do in order to trigger public hysteria and media curiosity: to stage his playing, technically and emotionally, with exaggerated gestures and grimaces, program a few pieces capable of arousing thunderous applause, indulge in numerous encores, and thank the audience with hand on his heart. A good publicity agent would have helped to create an attractive image of glamour or non-conformity, on or off-stage,

Not only did Istomin refuse these compromises, which would have given him the impression of prostituting himself by making music the instrument of his success – he did the exact opposite. An example of this was his refusal to give more than two encores. He chose an introspective piece as the second encore, announcing before playing that he would be taking his leave with this piece. In so doing, he cut short the effusiveness and applause of spectators who were hoping for more encores. In the same way, he was reluctant to play an encore after a concerto, finding it almost inappropriate to occupy the stage alone in the middle of an orchestral concert.

More than a lack of charisma, which some have regretted, it was a deliberate approach which proved to be very damaging in terms of career. During the May 1971 recital mentioned above, Bernard Jacobson expressed his disappointment at the strange functioning of the American musical world in the Chicago Daily News: “If cabotinage was the benchmark measure of artistic merit, it could almost be understood that Istomin has not played with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in seven seasons, although he had once been a frequent guest, or that his recital in the Orchestra’s main hall was the first he had given here.”

Performing: a combination of happiness and suffering!

For Istomin, giving concerts was a matter of course. From a very young age, he knew that this would be his life, nearly a divine mission. Of course, the idealized vision of the easy life of a virtuoso soaring unconcernedly from one triumph to the next, quickly came up against reality. He discovered that music was not only an art, but also a business, and that the making of a career depended a great deal on the critics. In both these areas, artistic competence and honesty were rarely guaranteed. Istomin also became aware of his responsibility towards the public, other musicians – and even more so, composers. “The prospect of the perfect performance leads me on. (…) The work itself is very important to humanity. One has a responsibility as a person who has been given – through no fault of his own – a gift. To walk away from that while I still have the capacity for growth – that would be the greatest failure.” This sense of responsibility generates stage fright, a suffering that is almost impossible to get rid of.

For Istomin, giving concerts was a matter of course. From a very young age, he knew that this would be his life, nearly a divine mission. Of course, the idealized vision of the easy life of a virtuoso soaring unconcernedly from one triumph to the next, quickly came up against reality. He discovered that music was not only an art, but also a business, and that the making of a career depended a great deal on the critics. In both these areas, artistic competence and honesty were rarely guaranteed. Istomin also became aware of his responsibility towards the public, other musicians – and even more so, composers. “The prospect of the perfect performance leads me on. (…) The work itself is very important to humanity. One has a responsibility as a person who has been given – through no fault of his own – a gift. To walk away from that while I still have the capacity for growth – that would be the greatest failure.” This sense of responsibility generates stage fright, a suffering that is almost impossible to get rid of.

It was not success which Istomin was looking for when performing – he was even afraid of having too great a success, which only the composer deserved! What he wanted was to share the musical truth: “My first ambition is to speak, to communicate the truth, as well as I can, in the music I am playing. After a performance that’s really been what I wanted it to be, I feel a wonderful light sense of having spent myself, having fulfilled myself. The moment of truth is the doing.”

Documents

Istomin paid a great deal of attention to the first piece on his recital programs. He wanted to start with something which would allow him to release his excess adrenaline without causing too much stress. For many years, the little Haydn Sonata in A major Hob.XVI:12 was the ideal work for him to begin the concert smoothly. This recording was made in 1969 at the Stratford Festival.

.

In the early 70s, Istomin used to start his recitals with an underrated piece by Beethoven, the Fantasy in G minor Op. 77 which he carried over into his all-Beethoven programs in the late 80s and early 90s. This live recording was made at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on October 31, 1991.

.

Mendelssohn. Song Without Words Op. 62 No. 1 was Istomin’s favorite encore in the latter years of his career. This document was filmed in Martigny during the Montreux Festival 1989. As he nearly always did, he announces the piece and says (in French) that with it, he will be taking his leave of the audience.

.