“I’ve performed more than three thousand concerts, and there hasn’t been a single one in which I haven’t suffered from stage fright. All great artists are nervous. Casals suffered from stage fright his whole life! I still remember the first concert at the Prades Festival in 1950. When he sat down to play the Bach First Suite for cello, I could see that his leg was trembling!”

In September 1979, Earl Lane, a prominent science journalist who worked for Newsday, published a report entitled “Stage Fright: The Artist’s Private Curse”, in which he interviewed outstanding musicians such as Eleanor Steber, Isaac Stern, Charles Rosen and Eugene Istomin. Rosen pointed out that the staging of the concert was established in the 19th century and that it had hardly changed during the subsequent one: ‘’The stifling air of the concert hall, the unnatural costume of the performers, the harsh lights – all this is meant to turn play into performance, into a dramatic art midway between melodrama and decathlon.“ Rosen stated that “tennis costume is obviously the only reasonable clothing for a pianist’’.

The discovery of stage fright

Stern said that only children (and those who are unconscious) do not experience stage fright. Istomin remembered that he played for Rachmaninoff when he was seven years old, and that he hadn’t even been nervous. Ten years later, he would have been paralyzed with fright!

Istomin believed that stage fright was “a kind of loss of innocence, a fall from grace: It is only when there is the prospect of possible disapproval or failure that stage fright appears.” He said that he first experienced it when he was nine years old: “I had the intuition that I was being tested. I didn’t really understand what was going on, but for the first time I asked myself: ‘Do you know the music?’. On that same afternoon, a young girl was playing the Fantaisie–Impromptu by Chopin. When she reached the end of the piece, she could not find her way to the last chord!” It was a very troubling incident for Istomin that he would remember all his life.

The trauma of his debut in New York

Another trauma was to play a significant role in the development of Istomin’s stage fright, that of his first concert with the New York Philharmonic. A few days earlier, his debut in Philadelphia had gone well, but in New York it was a different matter. It was quite daunting for a very young pianist to play at Carnegie Hall, especially since the concert was broadcast live throughout America. Istomin was overcome by intense stage fright, and the final blow came when he sat down at the keyboard and discovered that it was not the piano he had chosen. The one which had been assigned to him had a heavier mechanism and very smooth keys which the fingers could not grip well. Many years later, Istomin still wondered how he had managed to reach the end of the first movement of the Brahms Second Concerto! It was only in the third movement, the Andante, that he managed to regain his foothold. However, the audience was enthusiastic (despite five curtain calls, he did not dare to play an encore) and the criticism was benevolent. The post-concert was a whirlwind of contradictory emotions: compliments from Busch and Huberman and harsh judgment from Serkin. As the recording on acetates shows, the overall performance was good, even superb at times, but Istomin was aware that he had not lived up to what he and others (Leonard Bernstein, for example) expected. Most of all, he had felt a deep malaise and the vertigo of losing control over himself.

Stage fright had settled into the heart of his life and he never succeeded in ridding himself of it. The first five years of his career had taken him to the top but he was not happy. He suffered an identity crisis. At the same time, he was emerging from adolescence and beginning a career, in a rather hostile world (of managers and critics!) where he felt constantly judged. Even though he was successful, he experienced frustration, with the fear of not being able to give of his best on stage. He was on the verge of burnout and depression.

Istomin decided to take a six-month sabbatical in the spring and summer of 1948 (the only one of his entire career!) and left for France. Following in the footsteps of Hemingway, Fitzgerald, and countless musicians who came to study with Nadia Boulanger, he wanted to discover France. He knew the language without having ever really spoken it. Above all, he wanted to take a break, to escape and to feel free. He hoped that it would help him to find a sense of purpose in his life as a pianist, and to resume his career in a more positive spirit.

Stage fright and psychoanalysis

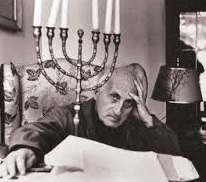

When he returned to New York, Istomin was still confused. Mrs. Leventritt, the great patron of musicians, was alarmed to see such a talented young pianist in this condition. She suggested psychoanalysis, asserting that it would certainly be beneficial and might help him to overcome his stage fright. In the late 1940s, psychoanalysis was very popular among American artists and intellectuals, especially musicians. Istomin’s situation made the idea perfectly logical. One could think that certain elements of his childhood played an important role in this obsession: the overprotectiveness of his mother and aunt, an only child raised far away from other children, a tendency developed very early on to escape into imaginary worlds. For Istomin, the spectacular and abrupt debut of his career came as a real shock, with the impression of having been thrown on stage like a lion into the arena, to be tested by the public and critics! It brought out the modesty he had felt very early on when he was surrounded by naked dancers in the dressing rooms of his parents’ cabaret, or when he refused to swim naked in the kindergarten pool. Istomin often said of a concert that it was like appearing naked on stage. He disliked pianists who showed their emotions by making faces and gesticulating. Emotions should arise only through the music! Istomin felt both the desire for and the fear of success, as it was inevitably superficial. In any case, he was not willing to make concessions to facilitate it, either by the choice of his repertoire or by his attitude on stage. He thought that much of his stage fright came from his sense of responsibility towards the composer, whose works had to be performed as faithfully as possible, as well as towards the gifts he had received and which he felt obliged to develop as far as possible.

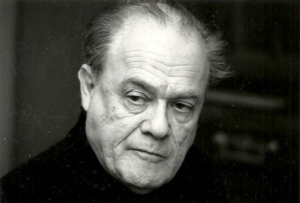

Although initially reticent, Istomin, accepted Mrs Leventritt’s advice, and began an analysis with Dr. Bychowski, a psychiatrist who had studied with Freud himself and had translated his Introduction to Psychoanalysis into Polish. Gustav Bychowski was a great intellectual with insatiable curiosity and had written countless books and articles on a wide range of topics, from Proust and his Mother to Dictators and Disciples from Caesar to Stalin. He had deviated from Freudian orthodoxy, and Istomin’s analysis was far from traditional! Bychowski made friends with his patient, not asking him for money, and inviting him to dinner, sometimes with other patients such as conductor Erich Leinsdorf. He no longer believed in the need for “transference” and instead used psychoanalysis as a means of learning about the human being. Although it failed to cure Istomin of his stage fright, this friendly relationship nevertheless allowed him to gain more insight into himself, to understand his stage fright better and to become aware that he would have to live with it until the end of his career. Giving concerts was his mission, and this was the price which had to be paid.

Istomin appreciated this experience enough to advise his friend William Kapell to consult Dr. Bychowski. To Istomin’s amazement, Kapell accepted and was satisfied with the first sessions, shortly before his tragic plane crash.

Manifestations of stage fright and ways to prevent them

Earl Lane reported that for Istomin ‘’the tension and physical requirements of performance often lead to perspiration which moistens his hands, causing his fingers to slip off the keys. When he is playing a piano with ivory keys, the problem is less severe, but when the keys are coated with plastic Istomin says the surface offers less grip. He has taken to brushing them lightly with steel wool to improve matters, and he uses a resin bag for his fingers.”

Nervousness and adrenaline rushes could also disturb the playing and cause wrong notes. Stage fright, which had probably affected musicians of all epochs, became much more intense with the appearance of the LP. Audiences expected the same perfection as on a record, and wrong notes became unacceptable. As a consequence, musicians were forced to give priority to control over inspiration. Istomin regretted this, but admitted that he too was a victim of the obsession with perfection, as were the vast majority of his colleagues.

Among the manifestations of stage fright, there is also the fear of memory lapses. Istomin hardly mentioned it and seemed to have never experienced any significant ones, but the possibility remained in his subconscious.

To mitigate the consequences of stage fright (possibly complicated by problems caused by a deficient instrument, poorly adjusted lighting or unfavorable acoustics), Istomin relied primarily on repeating passages, sometimes very slowly. He wanted to create a kind of automatism by conditioning his reflexes, which would bring him technical safety and allow him to give free rein to inspiration. The limitation of his repertoire, in concerto and especially in recital, met the same concern. In chamber music, there was no question of playing a work that was not perfectly prepared, even though he had the score in front of him.

Another way to reduce stage fright was for Istomin to stop performing as rarely as possible. From the mid-1950s to the early 1980s, his seasons almost always exceeded 100 concerts. Each time he resumed playing after a period of inactivity his stage fright seemed to reappear with more intensity!

Stage fright and competitiveness

Earl Lane left the conclusion of his article to Istomin, who explained that ‘’much of the real anxiety ascribed to stage fright probably results from the competitiveness in the world of classical music. ‘It took me most of my career to come to that realization’, Istomin said. ‘What bothered me, and what I resented, was being put into a situation where I’d be compared to others. Music is supposed to be an act of love. But what they were telling me was, ‘Go ahead and love, but we’ll tell you how you fit into the category of lovers.'” Asked why he continued to face this anxiety, Istomin answered: “The prospect of the perfect performance leads me on.”