As his musical ear had been awakened by listening to his parents’ singing, Istomin always found himself extremely attracted to stringed instruments, the closest to the human voice. When he mentioned the musicians who inspired him, he cited almost as many violinists and cellists as pianists. This is what he said about Heifetz: “In proportional terms, relatively speaking, it is as mysterious, as miraculous, as Mozart. Regarding performance, he is a genius, a prodigal son; he is the greatest instrumental miracle I have ever known – greater than any pianist! He had an enormous influence on me. It was almost an obsession for me during a certain period. It was as inspiring for me as the singers.”

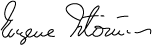

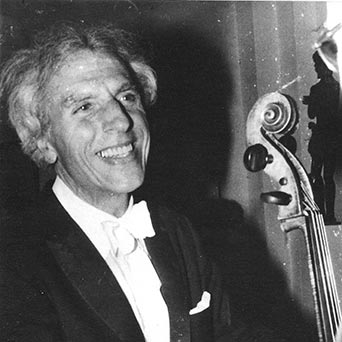

Istomin loved to accompany singers, and did so quite often at the Prades and Puerto Rico festivals, playing Schubert, Schumann and Brahms lieder. He even provided an impromptu accompaniment to Luciano Pavarotti and Renata Scotto at a private party. Above all, he took great pleasure in interacting with string instruments, in sonatas, trios, quartets or quintets. His dialogue with the strings could sometimes seem like a rivalry in the art of singing! Isaac Stern wrote in his memoirs, My First 79 Years: “Eugene had the most uncanny ability to make the piano sound as if he, too, had a bow, and a brilliant sense of the harmonic basis of any phrase, and a flexibility in phrasing that was as natural as using the bow for Lennie and me.” Jaime Laredo, who often played with him in different ensembles, said that no pianist “could match a string sound as well as Eugene”. Istomin was even tempted to move his finger on the piano key, as though he could produce a vibrato.

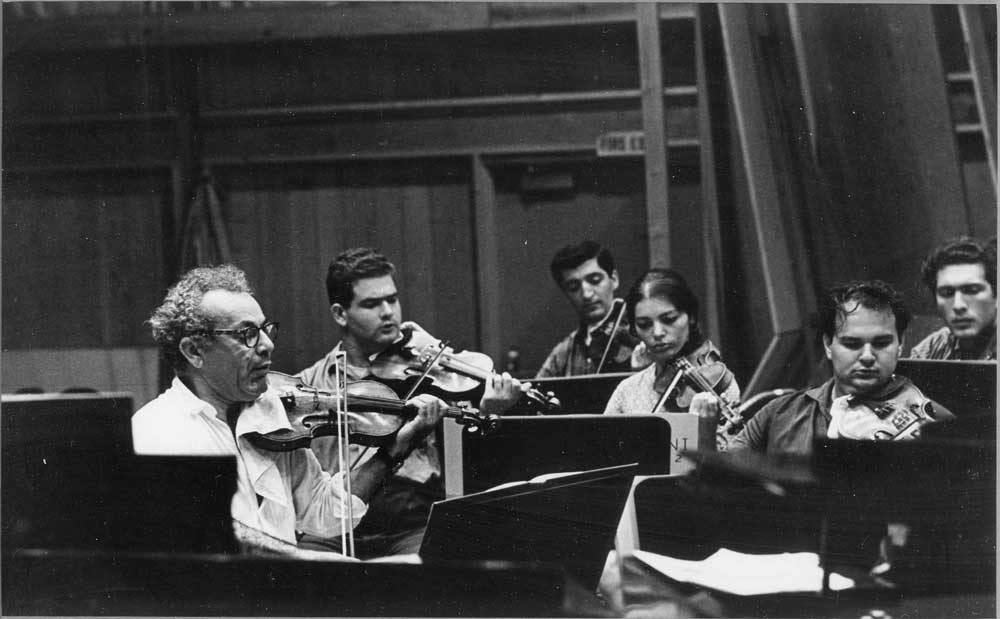

This rare ability earned him the appreciation and support of great violinists and cellists, not only among his contemporaries but also amongst his elders. Adolf Busch had championed him in the jury of the 1943 Leventritt Competition and immediately hired him as soloist for two major tours with the Busch Chamber Players. Pablo Casals immediately received him as one of the chosen few, and declared that if he had to resume his career, he would choose to play with Istomin. It was an amazing statement and a spectacular way to be anointed by the elite. Istomin thus became part of the small circle of great musicians who recognized and supported each other. It was these two musical giants who introduced him to chamber music.

Another great violinist was in attendance when Istomin made his debut with the New York Philharmonic: Bronislaw Huberman. In 1896, when he was just thirteen years old, Huberman played the Brahms Violin Concerto in the presence of the composer who, at first skeptical in front of such a young musician, finally gave way to enthusiasm. He copied out for him the first two bars of his concerto, with this dedication: “In fond memory from an overjoyed and thankful listener.” After hearing Istomin play the Brahms Second Concerto, Huberman told him in turn: “Young man, I played Brahms’ Violin Concerto for Brahms himself, and I can assure you that tonight he would have been very happy!”