Relations between Leonard Rose and Eugene Istomin were both musically and humanely complex. This matter is covered at length in the articles devoted to the legendary trio they formed together with Isaac Stern. Here are some additional elements on the events and ideas they shared, apart from the trio.

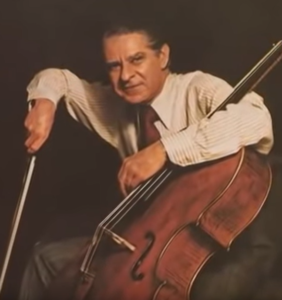

The obsession with perfection to the point of neurosis

In his autobiography, Isaac Stern gives this brief portrait of Leonard Rose: ‘’Lennie was a well-built, very good-looking man about five feet eight, and a driven neurotic. He was a very successful teacher, knowledgeable, patient, but he couldn’t get away from his nerves. He had to practice so many hours a morning, every morning. At four o’clock in the afternoon on the day of a concert, he had to have a steak and whatever came with it. No other food. Invariably, he was at the hall an hour before the concert, when he’d begin with a series of little exercises to warm up. But he always played through his nervousness, went right through it to the performance which was unfailingly brilliant.”

In The Pleasure Was Ours, the book of memories which she wrote together with her husband, Virginia Katims recalled that one day Rose was scheduled to play Schelomo with the Seattle Symphony but arrived late because the taxi driver got lost. He strongly urged them to move the Bloch piece to the second half, as he did not have enough time to warm up, but the conductor, Milton Katims, refused. When the first piece on the program came to an end, it was Rose’s turn to come on stage, but he was still practicing. He had to be searched for in his dressing room and was so distracted that he nearly went on stage without his jacket! Virginia Katims also remembered a very lively dinner at which Rose was laughing heartily at Milton’s jokes. When dessert was served, he suddenly stopped and said: ‘My God, I’m here having fun, while I have a concert tomorrow night!’ He immediately became serious again and soon took his leave. Istomin was also very serious and nervous before a concert, but he was clearly surpassed by Rose! .

Istomin held Rose in high esteem, writing to his friend Eugenie Anderson in 1963: “He is the greatest cellist of our time, whose only possible rival is Rostropovich”. Like all those who heard him, Istomin was very touched by the beauty of his sound, which was without doubt one of the most gorgeous in the history of the instrument.

When Rose played trios, his nervousness was rarely a problem, unlike in sonatas where he could be overwhelmed by adrenaline and speed up the tempo, especially in the final fugue of Beethoven’s Opus 102 No. 2. Istomin was compelled to follow him, while trying to hold back the tempo in order to avoid a disaster. This also happened occasionally in the Sonata Op. 5 No. 2, notably at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées where Rose precipitated the tempo of the Allegro molto of the first movement and Istomin refused to follow him! There were heated discussions backstage after the concert was over to find out who was responsible for the mishap!

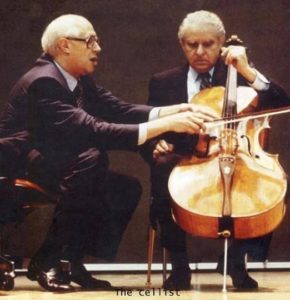

The shadow of Casals interposed itself between them whenever they performed duos. After having played for so long with Casals, it was difficult for Istomin to collaborate with any other cellist! He once told Thornton Trapp that when he played with Rose, their performances were invariably civilized and knowledgeable, but never ecstatic. As for Rose, he sensed Istomin’s reticence and felt even more acutely a rivalry with Casals, who is already an embarrassing reference for all cellists!

Rose and Casals

In the early 1980s, Leonard Rose came to the Prades Festival three years in a row. In 1982, he gave an interview to the French Television and reminisced about a visit to Casals: “I have forgotten the year. Casals was probably about 80 years old. I made the trip just to meet him. He absolutely loved my cello. He took it and played it, wonderfully. I was curious and asked him to play some movements from the Bach Suites. I was curious to see how he played them. I must say that since I was a little boy, Casals was my God. I had never heard him in concert when he was at his peak. By the time I heard him, he was already old. I knew a lot of his recordings. I wanted to be another Casals, which was obviously impossible because Casals was unique. Casals played the same role as Toscanini for conductors. Toscanini came at a time when conductors, especially German conductors, were taking absurd and unnecessary liberties with the scores, with the tempos, making useless ritardandos and changing the orchestrations. Toscanini came along and said: ‘No, we shouldn’t make these ritardandos.’ It so happens that I played with Toscanini. In 1938, it was my first job, as second cello of the NBC Orchestra. I think Casals played the same role for cellists. Casals was a modern cellist. He developed a completely new system of fingering. For example, one of Casals’ great desires was to use the glissandos only for musical reasons, and not for technical ones. He was particularly careful to phrase by avoiding all the glissandos that made no musical sense. He made it a point to play perfectly in tune. The question of intonation was central to him. It must be said that, before him, cellists played rather carelessly…”

It seems that Rose never told anybody about this visit, and his biographer, Steven Honigberg, did not mention it. There is no trace of it in Casals’ correspondence, nor in Marta Casals’ memory. One wonders whether this visit was more of a dream than a reality. What is certain is that Rose had the opportunity to spend time with Casals at the first Israel Festival and to talk with him as much as he wished. Casals was very friendly with him, in Israel and also in Puerto Rico when the Trio played the Beethoven Triple Concerto under his direction. Rose, who was always especially nervous when he performed this work, missed an entry at the dress rehearsal, but played very well at the concert. Casals’ compliments went straight to his heart.

Agreements and disagreements

Politically speaking, Rose and Istomin were very close. They were strong supporters of the Democratic Party in its defense of civil rights and social progress. They shared the same empathy for Kennedy, and Rose considered his meeting with him at the White House in 1962 to be one of the highlights of his life. Rose readily joined the Committee of Artists and Writers chaired by Istomin for supporting Hubert Humphrey in the 1968 presidential election.

Istomin and Rose met in New York in 1943. Rose had just joined the New York Philharmonic. At Istomin’s debut on November 22, 1943, he sat next to the principal cello, Joseph Schuster, and subsequently let his elder colleague play the famous solo in the Andante of Brahms’ Second Concerto. Rose became principal cellist the next year and participated in all the concerts Istomin gave with the New York Philharmonic until 1951: under Rodzinski (Beethoven 4 and 5, in 1944 and 1946), Szell (Chopin 2 in 1948) and Stokowski (Mozart K. 271 in 1949). Istomin and Rose also had many opportunities to play chamber music together informally in New York, as they were part of the same small group of musician friends.

The musical collaboration between Istomin and Rose was very smooth, as long as there was no need for words and their sense of intuition matched, but as soon as there was a discussion, it could become very heated. Istomin was always convinced of his musical ideas and not at all diplomatic in the way he expressed them. Rose, who drew upon his vast knowledge of the repertoire and his experience as a teacher, did not give in easily! Rose and Istomin gave very few duo concerts but they played sonatas in various chamber music programs, especially for the debut of the Trio in Ravinia and throughout the Beethoven year. The Brahms Second was one of their favorites, as Rose was particularly fond of the second movement which, according to him, was one of the peaks of Brahms’ music. It should be noted that Rose recorded the Brahms Sonatas in August 1982 with Istomin’s closest disciple, Jean-Bernard Pommier.

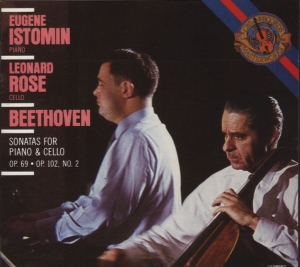

In 1970, Istomin’s decision to give up recording the Beethoven Cello Sonatas because of his conflict with Columbia was a tragedy for Rose. He considered this project as “the realization of a lifelong ambition”.

Generosity and resentment

This decision might have caused the Trio to break up if they had not already committed themselves to so many engagements during the Beethoven bicentennial year. The atmosphere of the first concerts, in May 1970, was very strained, with resentment from Stern and especially Rose still very strong. However, their musical complicity seemed almost intact and friendship prevailed. Rose showed great concern for Istomin when he suffered from back or dental problems, and even offered to page turn for the Kreutzer Sonata. Istomin would have been delighted to accept but he eventually refused, as he thought it might be detrimental for Rose’s public image.

The wound never healed, and even reopened in the early 1980s when Rose learned that Istomin and Stern were about to complete the recording of the Beethoven Violin Sonatas. He was angrier with Stern than with Istomin! Rose found it inconceivable that Stern would record these sonatas with Istomin after what had happened in 1970. To his mind, Stern should have recorded them with another pianist! He himself had thought of doing this with Van Cliburn but it proved to be impossible.

This resentment did not prevent him from demonstrating surges of friendship. When Istomin’s mother died in 1979, Rose wrote to him: “My dear Eugene, June told me the sad news about your mother this morning. After my mother died about five years ago, your letter meant so much to me. I don’t have the ability to write in such an exquisite manner but do hope I can convey my thoughts of warmth and love. Please know I send you an embrace and sincere sympathy. Xenia joins me in sending love to you and Marta. As ever, Lennie.” Rose sent another very moving message to Istomin in 1981: “I cannot resist writing you — Just listened to our C minor Mendelssohn — the overall performance is glowing, beautiful and spirited. It’s important to me to tell you how overwhelmed I was with your playing. The brilliant technical mastery and sensitive musical ideas were touching. Much love.”

These contradictions were typical of Rose. In the memoirs he intended to publish, he wrote that Istomin regarded Beethoven’s chamber music like piano concertos accompanied by strings and that he stubbornly insisted on playing with the piano lid fully opened, regardless of the acoustics of the hall and the sound of the piano. But a little further on, he asserted that the balance with the piano was almost always adequate. On one hand, Rose was very generous with his students, giving them confidence and allowing them to develop their own personality, but on the other hand he could be mean-spirited when they were inspired by another cellist or when their own careers took off. Rose suffered from never being recognized for his real value. He always felt as though he were competing with other cellists and was jealous of those who captured the attention of the media, especially Piatigorsky and later Rostropovich. He harbored a bitterness about this which, from time to time, invaded him beyond all reason.

In 1980, the Trio toured in January and February and was scheduled to give a series of concerts in Detroit in April, which Rose missed due to breaking his bow arm. The Trio was destined to meet again only for concerts in tribute to two personalities who had been very important in their lives: Supreme Court Judge Abe Fortas and President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Rose’s career was markedly in decline, but his activity as a teacher was intense and productive. In April 1984, he was diagnosed with the same leukemia that his first wife had not been able to overcome twenty years before. Istomin supported him as much he could in his fight, coming to see him every time he was in New York and frequently talking to him on the phone.

Leonard Rose died on November 16, 1984. Istomin participated in the concert organized by the Juilliard School in his honor on November 27, along with Stern, Lynn Harrell, Yo-Yo Ma, Itzhak Perlman and Michael Tree. Istomin hoped that the recording of the two Beethoven Sonatas they had made in 1969 would be released before Rose’s death. Stern tried to persuade Columbia, but the CD was not released until two years later and made only a brief appearance in the catalogue.

Recordings

1969, July. Beethoven, Sonata No. 3 in A major Op. 69, Sonata No. 5 in D major Op. 102 No. 2. CD CBS MK 42398

1961, December 3. London, BBC studios. Brahms, Sonata No. 2 in F major Op. 99.

.

A few concerts (apart from those of the Trio)

1961, March 3. Washington. Library of Congress. Beethoven, Sonata No. 2 in G minor Op. 5 No. 2, Sonata No. 3 in A major Op. 69, Sonata No. 5 in D major Op. 102 No. 2. Recorded concert.

1961, March 3. Washington. Library of Congress. Beethoven, Sonata No. 2 in G minor Op. 5 No. 2, Sonata No. 3 in A major Op. 69, Sonata No. 5 in D major Op. 102 No. 2. Recorded concert.

1969, July 22. Stratford (Canada). Beethoven. Sonata No. 5 in D major Op. 102 No. 2. Recorded concert.

1973, November 11. New York, Carnegie Hall. Brahms, Piano Quartet No. 2 in A major Op. 26, with Isaac Stern, violin and Jaime Laredo, viola.

1973, June 17. Puerto Rico. Mozart, Piano Quartet in G minor K. 478, with Isaac Stern, violin and Abraham Skernick, viola.

1975, June 19. Puerto Rico. Brahms. Sonata No. 1 in E minor Op. 38. Recorded concert. .

Music

Beethoven. Variations on “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen” WoO 46. Eugene Istomin, Leonard Rose. Live recording on October 8, 1970.

Audio Player.

Brahms. Sonata No. 2 in F major Op. 99, second and third movements (Adagio affettuoso and Allegro passionato). Eugene Istomin, Leonard Rose. Studio recording in December 1961.

Audio Player