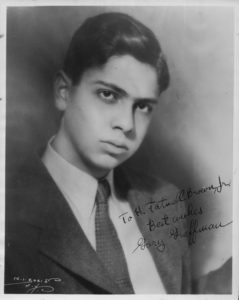

Gary Graffman feels that he already knew Eugene Istomin before he emerged from his mother’s womb. Their respective parents were part of the same group of Russian emigrants in New York. Although Gary was three years younger than Eugene, he entered the Curtis Institute four years earlier in 1935 at the age of seven. He enjoyed a unique privilege: Isabella Vengerova taught him not in Philadelphia, but at her apartment in New York, a few blocks from Gary’s home.

Gary Graffman feels that he already knew Eugene Istomin before he emerged from his mother’s womb. Their respective parents were part of the same group of Russian emigrants in New York. Although Gary was three years younger than Eugene, he entered the Curtis Institute four years earlier in 1935 at the age of seven. He enjoyed a unique privilege: Isabella Vengerova taught him not in Philadelphia, but at her apartment in New York, a few blocks from Gary’s home.

Gary Graffman played an involuntary role in the evolution of Istomin’s musical training. When Istomin’s father realized that young Gary was practicing six or seven hours a day while his own son was only expected to play for an hour and a half and spent the remainder of his time reading, going for walks or to the movies, or playing baseball, he decided to take him away from Siloti and sent him to the Mannes School of Music, and later on to the Curtis Institute.

In his delightful autobiography, I Really Should Be Practicing, Gary Graffman humorously recounts the fascination he felt for Istomin when he began his brilliant career in the fall of 1943: “I went to his concerts and absorbed everything I could (more, of course, than Vengerova wished). In my eyes, Eugene was already an established artist, and when he finally deigned to recognize me on an adult level, when I was about seventeen, I hung on to his every word. (…) When we were still in our teens, he would address me as ‘Young man’. He kept me artistically honest. Sometimes he was brutally uncompromising – but he was just as hard on himself. (…) I think it was mostly Eugene Istomin who convinced me, around the time I was finishing Curtis, that the wisest course was to become hyper-critical of oneself… Don’t just play. Think! Think!”

In his delightful autobiography, I Really Should Be Practicing, Gary Graffman humorously recounts the fascination he felt for Istomin when he began his brilliant career in the fall of 1943: “I went to his concerts and absorbed everything I could (more, of course, than Vengerova wished). In my eyes, Eugene was already an established artist, and when he finally deigned to recognize me on an adult level, when I was about seventeen, I hung on to his every word. (…) When we were still in our teens, he would address me as ‘Young man’. He kept me artistically honest. Sometimes he was brutally uncompromising – but he was just as hard on himself. (…) I think it was mostly Eugene Istomin who convinced me, around the time I was finishing Curtis, that the wisest course was to become hyper-critical of oneself… Don’t just play. Think! Think!”

This relationship of subordination quickly turned into a fraternal one, musically and humanely, when Gary Graffman decided to apply for the Leventritt Competition in 1947, four years after Istomin – and won, in an incredible scenario. For the preparation of the concertos, Graffman was privileged to have two exceptional pianists to accompany him on the second piano: Eugene Istomin and Leon Fleisher! Here is how he describes working with the first one: “An experienced colleague like Eugene could also make the things harder (and later, in real life, easier) by anticipating in his accompaniment some of the unexpected little things that often occur in certain places – little changes of tempo, for example, which are not marked, but which frequently seem to happen; and teaching little signals the soloist must be prepared to convey to the conductor at certain points with a subtle accent, a nod of the head or even a raised eyebrow. (Eugene was very good on eyebrows). ‘Be prepared’ was the message coming from him at the accompanying piano.” Fleisher was less openly critical, but his help was no less valuable because he was the one who accompanied Graffman during the competition. He did so well that at one point Szell suggested that he should be awarded the Prize, and he inherited the surname of Phleisher Philharmonic!

This relationship of subordination quickly turned into a fraternal one, musically and humanely, when Gary Graffman decided to apply for the Leventritt Competition in 1947, four years after Istomin – and won, in an incredible scenario. For the preparation of the concertos, Graffman was privileged to have two exceptional pianists to accompany him on the second piano: Eugene Istomin and Leon Fleisher! Here is how he describes working with the first one: “An experienced colleague like Eugene could also make the things harder (and later, in real life, easier) by anticipating in his accompaniment some of the unexpected little things that often occur in certain places – little changes of tempo, for example, which are not marked, but which frequently seem to happen; and teaching little signals the soloist must be prepared to convey to the conductor at certain points with a subtle accent, a nod of the head or even a raised eyebrow. (Eugene was very good on eyebrows). ‘Be prepared’ was the message coming from him at the accompanying piano.” Fleisher was less openly critical, but his help was no less valuable because he was the one who accompanied Graffman during the competition. He did so well that at one point Szell suggested that he should be awarded the Prize, and he inherited the surname of Phleisher Philharmonic!

Istomin could not accompany him during the auditions because he was part of the jury! After the first round, the judges decided to cancel the semi-finals and qualify only one applicant for the final: Gary Graffman, who was nevertheless obliged to prove that he deserved to receive the First Prize. He had to play for almost two hours. George Szell was the only one with reservations, but he finally gave in. Graffman was now a full member of the famous OYAPs, thus joining Istomin, Fleisher, Lateiner, and Kapell. Within this community, an additional complicity existed between Graffman and Istomin, as they were the only ones who spoke Russian – and this allowed them some asides which had the gift of infuriating the others!

Istomin could not accompany him during the auditions because he was part of the jury! After the first round, the judges decided to cancel the semi-finals and qualify only one applicant for the final: Gary Graffman, who was nevertheless obliged to prove that he deserved to receive the First Prize. He had to play for almost two hours. George Szell was the only one with reservations, but he finally gave in. Graffman was now a full member of the famous OYAPs, thus joining Istomin, Fleisher, Lateiner, and Kapell. Within this community, an additional complicity existed between Graffman and Istomin, as they were the only ones who spoke Russian – and this allowed them some asides which had the gift of infuriating the others!

Graffman and Istomin also shared a multitude of interests other than music. Graffman had initiated Istomin into the art and history of China to such an extent that Istomin had begun a collection of Chinese ceramics. In 1971, Istomin planned to give concerts and master classes in China, a project that he could not fulfil as the Nixon administration refused to grant him permission. When Graffman had to put his career on hold because his right hand would no longer respond, he gave free rein to his talent for writing and his passion for photography. Istomin was deeply unhappy to see his friend Gary Graffman, fifteen years after Leon Fleisher, lose the use of his right hand. He admired the strength of character with which Graffman overcame this drama and the fantastic pedagogical work he undertook, both as a teacher and also as director of the Curtis Institute.

Istomin and Graffman shared many adventures over the years. In the spring of 1950, Graffman was unexpectedly free. Someone had closed a car door on his fingers and he had lost a nail, which prevented him from playing the piano for some time. He was thus able to accompany Istomin to Marseille (where Istomin played Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto under Paray) and to Prades, where he spent two weeks of an unforgettable vacation. While there, he attended most of the rehearsals and concerts – and participated in all the parties! .

In the last twenty years of Istomin’s life, there were other numerous occasions. In 1986, when Istomin established the William Kapell Competition, Gary Graffman was naturally one of the jury members. The following year, when Istomin began his famous tours across the United States, escorted by a truck transporting his own pianos, Gary’s wife Naomi Graffman chronicled the event in an article which appeared in The New York Times Magazine. In November 1990, Graffman participated in the concert which Istomin had organized as a tribute to Alexander Siloti.

Graffman played in November 2000 in the private concert initiated by Rostropovich for Istomin’s 75th birthday. Of course, he also responded to Istomin’s invitation to participate in Great Conversations in Music at the Library of Congress in December 2001, talking in the company of prestigious colleagues like Leon Fleisher, Emanuel Ax, Charles Rosen and Yefim Bronfman. This lifelong friendship did not end at Istomin’s death in November 2003. Ten years later, when Sony took the initiative to reissue his complete recordings, Gary Graffman prompted producer Robert Russ to republish Eugene Istomin’s recordings as well, which was done in December 2015.

Graffman played in November 2000 in the private concert initiated by Rostropovich for Istomin’s 75th birthday. Of course, he also responded to Istomin’s invitation to participate in Great Conversations in Music at the Library of Congress in December 2001, talking in the company of prestigious colleagues like Leon Fleisher, Emanuel Ax, Charles Rosen and Yefim Bronfman. This lifelong friendship did not end at Istomin’s death in November 2003. Ten years later, when Sony took the initiative to reissue his complete recordings, Gary Graffman prompted producer Robert Russ to republish Eugene Istomin’s recordings as well, which was done in December 2015.

Document

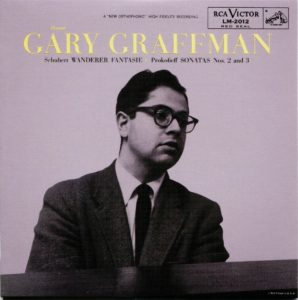

Gary Graffman plays Prokofiev’s Concerto No. 4 in 1990 in Moscow, with the Moscow Virtuosi under Vladimir Spivakov.