The years between 1979 and 1986 marked a significant collaboration with the major publishing house HBJ (Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovitch), which provided Istomin with an unexpected and very exciting opportunity to put his passion for books into action.

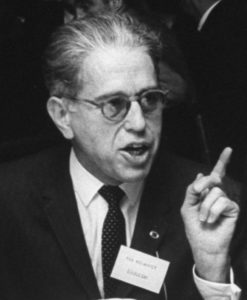

Kenneth McCormick, first experiences in the publishing world.

Istomin had already been close to another outstanding publisher, Doubleday’s editor-in-chief Kenneth McCormick. Capable of both faithfully retaining great writers and discovering new talents, McCormick had published the three best-selling books in America. He had also attracted prominent figures such as Presidents Truman and Eisenhower. McCormick perceived that, in addition to the spectacular rise of his career, Istomin’s rich personality would give substance to a very exciting book. As it was inconceivable that Istomin write his own autobiography since he was continuously on tour, McCormick decided to provide him with a dictaphone. Istomin’s accounts would be transcribed and then edited by a writer, probably by Irving Stone who had written some very successful biographical novels, notably on Van Gogh and Michelangelo. Istomin was very reluctant, believing that at the age of 32 he was far too young to publish an autobiography. McCormick insisted and Istomin promised to try, but too busy with travel and concerts and annoyed by having to manipulate the tapes, he finally gave up. McCormick tried a second time in 1970. He wanted to report the unprecedented challenge that Istomin and his friends Stern and Rose had taken up for Beethoven’s bicentennial: to perform his complete chamber music with piano in a series of eight concerts. All the ingredients of an engaging book were there: the musical achievement, the most beloved composer of all classical music, the spectacular clash of egos between the members of the Trio, the varied human and political context (from Buenos Aires to New York, through Brazil, Puerto Rico, Israel, Switzerland, Paris and London), as well as the many humorous anecdotes. Once again, Istomin was forced to record onto a tape machine – and yet again it proved to be too complicated, even with the help of his page turner, Thornton Trapp.

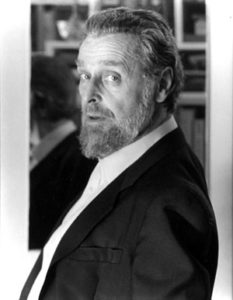

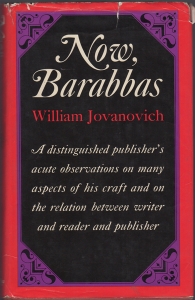

William Jovanovich

The adventure with Jovanovich was something completely different. One thing which Jovanovich had in common with McCormick was his ultra-fast ascent, but the two men were of quite different temperaments. Jovanovich, born in 1920 to a Montenegrin father who worked in the coal mines, and a Polish mother, arrived at school without speaking a word of English. He was able to enter the University of Colorado and received a scholarship to study English and American literature at Harvard. His studies were interrupted by the war, which he carried out as an officer in the Navy. He subsequently married, but due to a lack of funds, was unable to return to his university studies. He was hired by Harcourt & Brace as a textbook salesman. Seven years later, he became the company’s president. He increased the turnover of the modest publishing house from eight million dollars in 1954 to one billion three hundred million in 1990. .

A non-conformist who was fiercely independent and openly provocative, Jovanovich disrupted the quiet habits of the publishing world with his revolutionary ideas and competitive spirit. According to Rubin Pfeffer’s colorful phrase, quoted in the obituary of the New York Times, ”He stuck to his guns and did not jump on any bandwagon.” In 1970, he added his name to Harcourt and Brace, thus changing the company’s logo to HBJ. This ambition did not prevent Jovanovich from being deeply attached to the ideals of culture and education. Passionate about editing, he remained the personal editor of Hannah Arendt, Mary McCarthy and Diana Trilling despite his many occupations, as well as finding the time to write several books himself. Although extremely authoritarian, Jovanovich was also capable of trust. In 1961, he welcomed Kurt and Helen Wolff, whom Istomin had known in Busch’s circle, to HBJ and let them create a very prestigious publishing house under their own name, which would include renowned authors such as Günter Grass, Umberto Eco and Italo Calvino. .

A non-conformist who was fiercely independent and openly provocative, Jovanovich disrupted the quiet habits of the publishing world with his revolutionary ideas and competitive spirit. According to Rubin Pfeffer’s colorful phrase, quoted in the obituary of the New York Times, ”He stuck to his guns and did not jump on any bandwagon.” In 1970, he added his name to Harcourt and Brace, thus changing the company’s logo to HBJ. This ambition did not prevent Jovanovich from being deeply attached to the ideals of culture and education. Passionate about editing, he remained the personal editor of Hannah Arendt, Mary McCarthy and Diana Trilling despite his many occupations, as well as finding the time to write several books himself. Although extremely authoritarian, Jovanovich was also capable of trust. In 1961, he welcomed Kurt and Helen Wolff, whom Istomin had known in Busch’s circle, to HBJ and let them create a very prestigious publishing house under their own name, which would include renowned authors such as Günter Grass, Umberto Eco and Italo Calvino. .

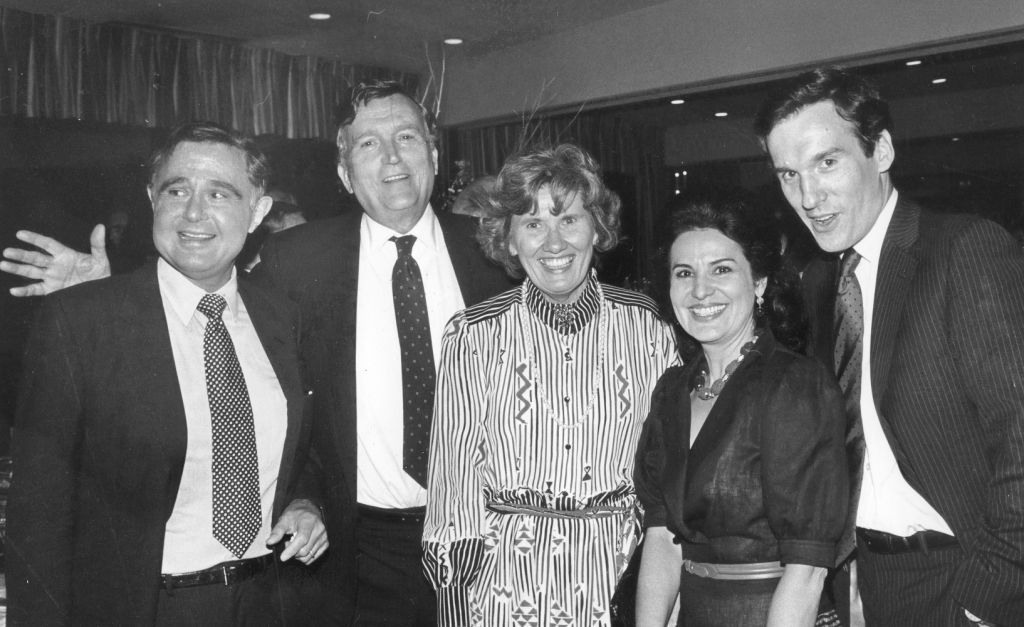

Marta and Eugene Istomin at HBJ

Towards the end of 1976, Jovanovich wanted to expand his Board of Directors, until then exclusively male, and was looking for a woman. The idea of approaching Marta Casals-Istomin was inspired by his wife, who had noticed the talent with which she managed the Puerto Rico Festival. The Jovanovichs invited the Istomins for dinner. Marta was convinced and agreed to join the Board. The collaboration went extremely well.

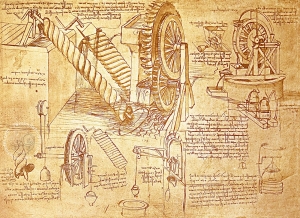

At the end of 1978, another dinner, this time at the Istomins’, would give an unexpected impulse to the already cordial relations between the two couples. Jovanovich discovered the richness of Istomin’s book collection, which proved that he was both a great lover of literature and a distinguished bibliophile. This resulted in a passionate discussion throughout the evening, at the end of which Jovanovich suggested that Istomin work for HBJ! He had just published a facsimile edition of the Codex Atlanticus, a fabulous collection of notes and drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, which was kept in the Ambrosian Library in Milan and remained inaccessible to amateurs: 1,119 leaves covering Leonardo da Vinci’s entire career from 1478 to 1519. The twelve volumes had been enthusiastically received around the world by wealthy connoisseurs. Jovanovich intended to continue and intensify the activity of his Johnson Reprint label. He was thinking of reissuing in facsimile the complete historical editions of some prominent English writers like Joseph Conrad. Istomin seemed to him the ideal person to supervise such projects.

A few days later, Istomin met Jovanovich and his team at HBJ’s offices. It was made clear that he would retain complete freedom to manage his time, and that this would not hinder his career as a pianist. Under these conditions, Istomin saw no reason to refuse such an exciting proposal. He was immediately appointed Advisor to the Chairman for Special Projects. He was given an office and an ideal assistant, Marie Arana, who was destined to have a wonderful career as a writer and critic. Marie Arana told James Gollin how Jovanovich portrayed Istomin, her future boss, whom she had not yet seen: “I don’t know anyone in the arts, in the fine arts, who is as engaged in the literary world as he is. He doesn’t care only about literary quality, but also about the physical quality of books. Bill was someone who really appreciated the smell of books and the feel of books and what leather is used, how rigid the spine is and what stamping is on it. It really impressed him that there was someone who not only understood literature, but also loved the art of the book!” .

Great editing projects

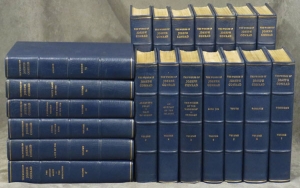

The first publication Istomin supervised was the 1921 Heinemann edition of Joseph Conrad’s complete works in twenty volumes. It was printed in London with the utmost care in 1980. A far more ambitious project was to follow: the fabulous collections of the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. Only a few paintings were sometimes lent for exhibitions in Western countries. Even the most enthusiastic amateurs who had made the trip to Leningrad could only see a very small part of the huge collections. One could only imagine the riches which, probably stored in poor conditions, were languishing in the reserve depots and cellars (nearly three million items). The project of presenting a nearly complete selection of the Hermitage treasures in a series of books made with the greatest care and the most modern technologies was incredibly exciting, even if it required considerable work and would be extremely costly.

For Jovanovich, it was obvious that Istomin was the only person capable of such a mission, through his understanding of the Russian soul and his mastery of the language, as well as his knowledge and passion for art and books. Istomin succeeded in bringing together a team of outstanding experts whose fields were perfectly complementary, as the collections ranged from the Renaissance to the Revolution of 1917: the Frenchman Pierre Rosenberg, then head of the painting department at the Louvre; the Englishman Philip Pouncey, a leading specialist in Italian Renaissance painting; the American Alan Shestack, director of the Yale University Art Gallery; and another American, Leo Steinberg, born in Moscow, who had changed the approach of art historians.

Istomin embarked on delicate negotiations with the Soviet authorities. Preliminary meetings were held in Paris, in particular to determine the amount of financial compensation provided by HBJ in exchange for authorizing the publication and granting exclusive rights. In October 1980, Istomin went to Leningrad with his artistic team to meet the curators of the Hermitage, and everything seemed to be going smoothly. Unfortunately, the political situation deteriorated. The Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December 1979 and diplomatic tensions continued to rise throughout 1980, with the United States even calling for a boycott of the Moscow Olympic Games. President Carter decided that this cultural and technological cooperation program with the Hermitage Museum should be cancelled. With a heavy heart, Jovanovich, Istomin and his staff were forced to give up.

These experiences strengthened the friendly ties between the Jovanovichs and the Istomins. The two couples often met in the villa that the Jovanovichs had recently acquired in Cap-à-l’Aigle, Quebec, on the banks of the St. Lawrence. When the Istomins left New York for Washington, as Marta had just taken over the artistic direction of the Kennedy Center, the Jovanovich’s apartment was almost always at their disposal as a pied-à-terre in New York.

Until 1986, Istomin worked on various facsimile editions. The last one was devoted to the Wessex edition of the collected works of Thomas Hardy, published in 24 volumes by Macmillan in 1913. Two hundred and fifty numbered copies were printed on handmade paper by the presses of the famous London printing house Curwen Press, and beautifully bound in dark goat leather. Other writers were contemplated but had to be abandoned. These publications were very expensive and HBJ was in a difficult financial situation, especially since the British press magnate, Robert Maxwell, had taken it into his head to lay hands on HBJ, proposing to buy it back for $2 billion. Jovanovich refused, but was subsequently obliged to embark on a recapitalization project which led him to incur very heavy debt, thus causing the company to go into a gradual decline. He finally left in 1990.

Istomin also contributed to other projects, particularly Galina Vishnevskaya’s memoirs. They were edited by Marie Arana and published by HBJ in 1984 under the title Galina: A Russian Story. Recounting her personal life, but also the many difficulties of Russian artists and intellectuals confronted with the Soviet regime, the book was a great success and was translated into many languages.

This article draws most of its information from James Gollin’s book: Pianist, a Biography of Eugene Istomin.