Serving his country was a long-term obsession of Eugene Istomin. On Serkin’s advice, he took part in two competitions in order to avoid ruining his career on the battlefields of World War II – and won both of them. Serkin expected that these successes would help him to be exempted from military service, or to be assigned to the Morale Division in charge of entertaining the soldiers. Istomin had accepted this way of evading the war as an obligation of his destiny as an artist, but it turned out to be useless, since a heart arrhythmia was detected during his physical examination and would have justified an exemption anyway. Nevertheless, Istomin continued to feel indebted to his country and to all those who suffered or were killed. Adding further to this debt, he was grateful to the country which had welcomed his parents in exile and which had allowed him to become an artist.

Moreover, Istomin was convinced early on that the battles of the Cold War had to be won not only with guns but also by means of communication, especially in the field of culture. It was obvious to him that music, which is by nature a universal language, might play an important part in the international strategies. He campaigned for several decades to persuade the American governments to send their best soldiers to the cultural front, and personnally volunteered for any mission the State Department would entrust him with.

First missions

After a trial run in Iceland in February 1956, he accomplished his first long mission between April and June: fifty concerts in Japan, Hong Kong, Manilla, Saigon, Singapore, and Colombo. Time Magazine reported on it on August 6, 1956 in a short article entitled Musical Ambassador and sub-titled Paying a Debt: “They’re suspicious of us culturally’, he says, referring to people he met on his ANTA tour of the Far East. ‘But at that same time they’re pathetically anxious to hear what we have to offer’. In Japan in particular, Istomin found that audiences were attracted by the openness and spontaneity of Western music.” The article ended with a question about his schedule and missions: “When he would settle down to a calmer life? ‘Not for several more years’, replied Istomin. He was booked for concert tours through 1959. ‘It’s a duty,’ he said. ‘The technical demands of radio, television and the movies and the accumulated knowledge of the European artists have produced a generation of American musicians with superb technical equipment and promising artistry. We have an obligation to pass that on to other parts of the world. It’s a way of paying back what we’ve borrowed.”

In the fall of 1956, a Columbia newsletter sent to sales representatives and to record dealers highlighted Istomin’s constant touring: “Live Wire is the only expression that describes EUGENE ISTOMIN who – in the past five years – has played more concerts, traveled more miles, gotten more rave reviews from critics the world over – than any other living pianist. He is truly America’s A-1 Goodwill Ambassador – and wherever he has played – FAR EAST, EUROPE, SOUTH AMERICA, & AMERICA – he has created new fans and won for his native country growing respect and admiration as a cultural force in the world!”

Kennedy, the time of great expectations

When Kennedy entered the White House, Istomin and many artists and intellectuals hoped that cultural communication would finally be acknowledged as a weapon of choice. On this field, as mirrored in space exploration, the United States trailed far behind the USSR. The Soviets excelled in using their great musicians. In 1955, Oistrakh and Gilels’ tours in America were a spectacular demonstration. Sol Hurok, the famous impresario, who was very astute in promoting stars and sensationalizing events, reached an agreement with Gosconcert, the concert agency of the Soviet Union. Hurok accepted exorbitant fees for Soviet artists ($10,000 per concert). This represented an important income, all the more so since the artists received only one or two percent of the fee. A fantastic publicity campaign was mounted to prepare the American critics and audiences to be suitably ecstatic about the upcoming performances. In 1960, for Sviatoslav Richter, the audience was nearly hysterical. A laconic sentence from Gilels, which he perhaps never pronounced, was largely spread about: “If you think I am good, wait until you hear Richter!” The point that Richter had to wait until he was 45 years old before being authorized to perform in the West led audiences to believe that he was not an obedient Soviet citizen who dealt with the KGB. It even made him likeable. Everyone in New York rushed to listen to Richter’s recitals at Carnegie Hall. The reception was incredible, with rapturous applause and unrestrained praise, though Richter himself thought that he had not played well. Columbia issued the live recordings of his recitals as quickly as possible, and even without permission. Richter fought to stop the sales and to prohibit later editions.

The Soviet Union sent only outstanding artists and did it deliberately, in the right place and at the right time, so that it was reported all over the world. For instance, Rostropovich went to Cuba in 1961, at the time of the missile crisis. The photos showing the famous cellist playing for the workmen in a tobacco factory or in a sugar cane plantation were seen by millions over five continents. The superb propaganda affirmed the cultural achievement of the Soviet regime and its will to make culture accessible to everyone, everywhere. For their cultural exchanges, the American authorities had been sending mostly second or third-rate ensembles for a long time, like the Roger Wagner Chorale or the Illinois University Symphony Orchestra. The State Department would need to change its mind when seeing the enormous impact of a few events: Isaac Stern’s tour of USSR in 1955, Van Cliburn’s triumph at the Tchaikovsky competition in 1958, or Bernstein’s concerts with the New York Philharmonic in Leningrad, Moscow and Kiev in 1959. It was high time to set up a consistent policy which would establish the United States as a great country of culture and which would win over the hearts and minds of supposedly hostile populations. For that purpose, the ideal means was music, provided the best performers would be sent.

Istomin listened to Kennedy’s exhortation: “My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

Full of enthusiasm after meeting Kennedy at the White House in May 1962, when he had performed with Stern and Rose, Istomin intensified his approach. He was received by Dean Rusk, the Secretary of State, who proved to be very interested in his plan. Not only was Istomin entirely at the disposal of his country, but he assured Rusk that his most distinguished colleagues would also offer their services. The State Department would only need to meet the travel and accommodation expenses and thank them with a small reception or a letter from the President. Istomin had no doubt that such missions, which would allow them to be in touch with and to empathize with the youth and the elites of a country, would be far less expensive and more efficient than the grants given by the CIA to largely unreliable opposition groups.

Istomin’s ideas needed time to gain ground in the maze of the American administration. Time Magazine announced the Return of the Gentle Persuaders, on September 6, 1963: “Only the gloomiest philistine would question the spirit of the State Department’s cultural exchange program—its value is eloquently stated in pictures of Leonard Bernstein drawing admiring crowds in Moscow and Louis Armstrong flashing teeth and trumpet for fascinated Africans. Yet last year the program was suspended for a thorough reappraisal, and after six months of hearings, it was clear that the program’s practices had not always lived up to its promises. Last week, with a new and far better charter, the “reconstituted” program was under way again as the first of 14 music and dance groups selected. Most of the musicians are paid union scale and soloists usually work for less than their concert fee. Last spring Pianist Eugene Istomin volunteered a free month of his time for a four-nation tour that was among the year’s most successful. This year Ellington is donating his time for the price of his telephone bill; hip to the Duke’s grand manner, the State Department has wisely limited him to $100 worth of calls a day.”

On the other side of the Iron Curtain

In April 1963, Istomin spent two and a half weeks in Bulgaria, an experience similar to a novel by John Le Carré. He was met with hostility by the Bulgarian authorities, who tried by every means possible to derail his tour. Fortunately, he could rely on the strong support of the US ambassador, Eugenie Anderson. He was finally able to overcome all the obstacles (bad pianos, last-minute change of conductors, and various traps) and achieved a triumphant success. After Bulgaria, Istomin stopped over in three capitals of the Middle-East: Ankara, Tehran (where he had already gone two years earlier, with Isaac Stern) and Kabul. He wrote a complete report of his tour, full of relevant remarks and suggestions. He regretted that the administration did not pay more attention to his tour, in spite of the very positive feedback from the ambassadors who greeted him in Sofia and in Ankara. There was only a note in Department of States’ Newsletter (N° 26, June 1963) entitled “Sofia Cheers an American Artist”, and sub-titled “Excerpted from a recent address from Lucius D. Battle, Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs”. It detailed his musical and diplomatic adventure in Bulgaria and quoted the words of the Ambassador in Ankara: “Mr. Istomin’s visit had a definite political importance, quite apart from its artistic value.”

After Kennedy’s assassination and his replacement by Johnson at the White House, the expectation of an ambitious cultural policy faded. Dean Rusk was still Secretary of State, but Johnson did not attach any importance to that kind of plan.

Istomin accomplished one last mission, previously scheduled, in the spring of 1965: five weeks in the Soviet Union and one week in Romania. It was quite a prestigious tour, including two concerts with the Leningrad Philharmonic, the best Soviet orchestra. The trip to his ancestral land proved to be a very special experience. He did everything to ensure he would not be considered as a Russian pianist. In Bulgaria, when his success was too obvious to be denied, the representatives explained that his name proved he was actually Russian! He refused to play any concertos by Tchaikovsky or Rachmaninoff, proposing only those by Beethoven and Brahms. In his recital programs, he chose works by his best-loved composers – Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert and Chopin – and added a Sonata by Igor Stravinsky, indeed a Russian composer, but one who had fled the Soviet regime. Stravinsky’s return three years earlier had been a tremendous success, which was highly embarrassing for the Soviet officials who had fiercely critized his music for so long.

Vietnam and the time of disillusion

Despite the reduction in his diplomatic activity, Istomin was not discouraged. He insisted on being given authorization to travel to Vietnam and perform there in 1966. The war had been escalating since the previous year and the number of American troops had increased from twenty thousand to two hundred thousand. At that moment, Istomin, like most of the American political community and the majority of the population, thought this war was justified and, in a sense, necessary. Following the domino theory, initiated by Truman, the communist drive on South Vietnam had to be halted to avoid the neighboring countries from falling one after the other into communism. Left unchecked, all Southeast Asia would soon be propelled to the communist side.

Some American intellectuals had begun to protest, and several demonstrations took place in the larger American cities. As for Istomin, he remained persuaded that this war was justified and that America would prevail. In order to show his support and realizing that it was also necessary to fight by means of culture and communication, he wanted to give concerts and to meet young musicians in Saigon. Ten years earlier, he had met students and teachers at the Saigon Conservatory, who spoke French and played works by Debussy, Fauré and Chabrier. They had since vanished. The city was in chaos. Istomin could not give any concerts, since safety conditions could not be ensured. Barry Zorthian, the spokesman of the American government in South-Vietnam, suggested he should go to Djakarta where he might be more helpful in defending America’s cause and image. A plane was chartered for his exclusive use, and he was treated royally. In Djakarta he played a recital at the residence of the ambassador, Marshall Green. At that time, he had no idea of what was brewing in Indonesia, the coup fomented by the CIA and the programmed assassination of five hundred thousand Indonesian communists.

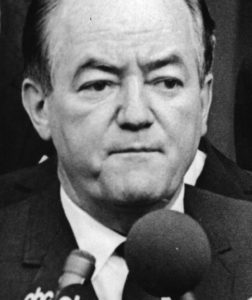

Both experiences fully discouraged Istomin from asking for or accepting other missions. When he learned about what was happening in Indonesia, he felt that he had been manipulated by the CIA. The coup in Greece the following year confirmed that the United States of America was no longer the idealistic, or even the realistic nation personified by Roosevelt or Kennedy. The CIA had become a state within a state, an uncontrollable institution with a formidable capacity to cause long-lasting harm. Its controversial director, Richard Helms, would later be given a two-year suspended sentence for lying. Istomin’s opinion about Vietnam changed after his visit. He became increasingly skeptical in spite of the triumphalist press releases, adopting Johnson’s famous sentence: “I don’t think anything can be as bad as losing, and I can’t see any way of winning.” During the presidential campaign of 1968, Istomin repeatedly urged his friend Hubert Humphrey to stand apart from Johnson’s policy and to declare his willingness to rapidly attain an acceptable peace agreement, which he probably did too late. . .

Last missions

In the years that followed, Istomin agreed to only a few occasional collaborations, like the inauguration of Manila’s Cultural Center in 1969 (at that time Marcos was not yet the despicable dictator he would later become), or the concert at the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal in 1976, a country which had recently freed itself from dictatorship.

It was not until 1979 that Istomin approached the State Department again. The circumstances were exceptional: the peace treaty between Israel and Egypt had been ratified on March 26 in Washington. A few weeks later, Istomin was to give concerts in Jerusalem to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Israel’s admission to the United Nations. He proposed to go first to Cairo and to give a recital and some masterclasses. The State Department and the Egyptian authorities were delighted to accept, and the visit was a great success. He was subsequently given the privilege of being the first artist to be allowed to travel directly from Cairo to Jerusalem. His initiative had a considerable impact in Egypt and in Israel, but did not attract the attention of the American media.

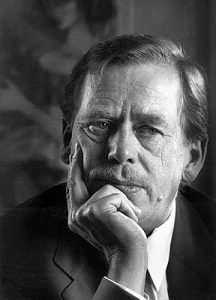

Istomin’s last diplomatic mission was his participation in the Budapest Cultural Forum in 1985. The forum was a gathering of prestigious representatives from the thirty-five countries who had signed the Helsinki Accords. It lasted six weeks, and was meant to confirm the end of the Cold War and launch a more constructive international cooperation. In addition to Istomin, the American delegation included distinguished personalities like the playwright Edward Albee, the architect Peter Blake, the choreographer Trisha Brown and the film producer George Stevens. The purpose of the Forum was to debate about the “creation, dissemination and co-operation, including the promotion and expansion of contacts and exchanges in the different fields of culture.” The discussions were quite positive at first, but then continued in a very conflictual atmosphere, reminiscent of the tensest moments of the Cold War. The Forum was scheduled to close with a joint press conference, but eventually the Soviet and American delegations each arranged their own. Kirichenko, head of the Soviet delegation, blamed the Western countries for having deliberately sabotaged the final press conference. Another Soviet official, Ivanov, accused the United States of physical and cultural genocide, racism and antisemitism, and of disregarding an enormous problem of illiteracy. He went on to charge the West of merchandising culture and of trying to introduce pornography, sexual perversion and chaos in the communist countries. Walter Stoessel, head of the American delegation, answered by recalling Gorbachev’s statement in the recent Geneva conference: “Let us stop saying stupid things to each other!” Istomin followed the discussions attentively. With the help of Edward Albee, he tried in vain to convince the Czech communist delegation to lift the ban on Catastrophe, the play which Samuel Beckett had dedicated to Václav Havel when he was in jail. Istomin went home convinced that despite some signs of liberalization, orthodox Communist ideology would continue to dominate for many years to come.