For Istomin, 1971 was the year of the Orient. In addition to the tour in Japan he made in early autumn, he was eager to realize his dream of playing in China, a country whose art and history he so deeply admired. His interest had been aroused by his friend Gary Graffman, a great specialist and passionate collector. However, this was not the only motivation for embarking on this adventure, which was rife with obstacles to overcome. Istomin was also deeply curious about the current state of this great country and he felt that it was of the utmost interest for the USA and China to draw closer. Indeed, since Sino-Soviet relations were very tense, an American-Chinese rapprochement would be a guarantee of balance and peace, with a reduction in Soviet influence. It seemed obvious to Istomin that music could play a crucial role in this process. What made the challenge even more exciting was that classical music had been banned by the 1966 Cultural Revolution and had not yet regained its place!

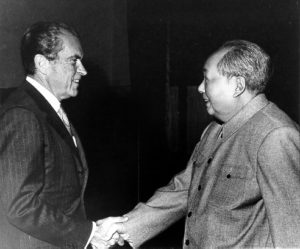

Istomin’s political goodwill, which had cooled somewhat since his unfortunate trip to Vietnam and Jakarta in 1967, sprang to life again when he realized that the situation was changing in China. In the spring of 1971, diplomatic relations between the United States and China were still cut off, and the Chinese government was still struggling to be admitted to the UN (this was finally obtained on October 26). But contacts were beginning to be established. The Nixon administration had made the first steps from 1969, which were interrupted by the American invasion of Cambodia in 1970. In December 1970, contacts had quietly resumed and were so promising that in April 1971 Nixon made a public statement of his desire to go to China. In July, Kissinger went there in secret to begin discussing important issues and to prepare for the President’s visit. When Istomin began his own efforts, no one would have dared to imagine the extraordinary success that Nixon’s trip would have in February 1972. It would be a major event in the history of the 20th century, cause a profound change in the world scene, and mark China’s first steps in the process of globalization.

In order to transmit his proposal to come and play for Chinese politicians and give concerts and master classes, Istomin was obliged to apply through countries which had already established official diplomatic relations with China. At that time, France was the country with closest ties to China. It had been the first major power to recognize the People’s Republic of China, as early as January 1964, and to establish extensive cultural exchanges. The most famous and respected French personality in China was André Malraux. His links to the Chinese Communist Party dated back to the 1920s, and the history of the Chinese revolution had been the source of inspiration for two of his greatest novels, The Conquerors and Man’s Hope. In the summer of 1965, Malraux, de Gaulle’s Minister of Culture, made an official visit to China and was received very amicably by Zhou Enlai and Mao Zedong. Istomin had met Malraux at the White House in May 1962 when he played with Stern and Rose, in celebration of the exhibition of the Mona Lisa at the National Gallery in Washington. He met him again in Paris, thanks to Jean-Bernard Pommier, and became friendly with the great writer. He found it easy to convince Malraux to personally intervene on his behalf with Zhou En-Lai. As for obtaining a visa, it was Hubert Humphrey who contacted the Secretary of State of Canada, a country which had already established diplomatic relations with China.

Everything seemed to be moving ahead smoothly, but negotiations dragged on and Istomin, bitterly disappointed, was forced to give up. He would never once travel to China. Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra were the first American musicians to be officially invited to China in 1973, after Nixon’s trip. However, it was Isaac Stern who took full advantage of the media coverage of the spectacular resurgence of classical music in China. He too had wanted to go there very early on, and in August 1971 had contacted Henry Kissinger, who dissuaded him from going. It was not until 1979 that he was able to make an extended tour of China, accompanied by a filmmaker. The result was the world-famous film From Mao to Mozart, which even won an Oscar.