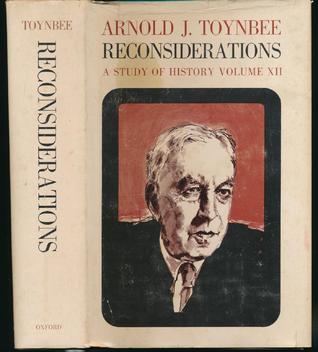

The tragic destiny of Greek civilization led Istomin to take an interest in the British historian Arnold Toynbee, who published the 12 volumes of A Study of History between 1934 and 1961. This extensive survey was presented as an analysis of the birth, development and decline of all civilizations. Toynbee theorized that each civilization is born from the need to meet challenges of various kinds: economic, technological or social. Its development can only be achieved through a creative minority that involves the entire population. As long as there are challenges to be met, civilization continues to develop, before declining inexorably of its own accord. Civilizations die by suicide, not by murder.

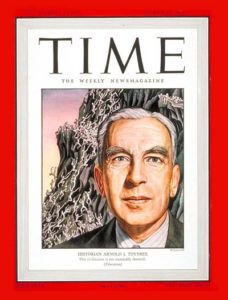

These theories are nowadays neglected, even if the current evolution of the world would seem to make them relevant again. Doesn’t Western civilization seem to be tempted by suicide? Toynbee seriously damaged his reputation and credibility by leaving his role as a historian to become involved in politics. His errors of appreciation of Hitler, changes of opinion on Israel and Palestine, and certain questionable positions on the USSR and the Cold War greatly harmed his image, but Toynbee was very trendy in the aftermath of World War II, especially in the USA. He was on the cover of Time Magazine in 1947 and his books became bestsellers. In France, it was more the philosophers who were interested in him, with historians blaming him for somewhat manipulating the facts to support his theories. Raymond Aron chaired a one-week symposium in Cerisy in 1958, which was entirely devoted to him and brought together leading philosophers and historians. More surprisingly, Gilles Deleuze, the creator of post-structuralism, quite often referred to him as a “lyrical historian” and valued his vision of civilizations.

These theories are nowadays neglected, even if the current evolution of the world would seem to make them relevant again. Doesn’t Western civilization seem to be tempted by suicide? Toynbee seriously damaged his reputation and credibility by leaving his role as a historian to become involved in politics. His errors of appreciation of Hitler, changes of opinion on Israel and Palestine, and certain questionable positions on the USSR and the Cold War greatly harmed his image, but Toynbee was very trendy in the aftermath of World War II, especially in the USA. He was on the cover of Time Magazine in 1947 and his books became bestsellers. In France, it was more the philosophers who were interested in him, with historians blaming him for somewhat manipulating the facts to support his theories. Raymond Aron chaired a one-week symposium in Cerisy in 1958, which was entirely devoted to him and brought together leading philosophers and historians. More surprisingly, Gilles Deleuze, the creator of post-structuralism, quite often referred to him as a “lyrical historian” and valued his vision of civilizations.

In 1959, Istomin used the opportunity of visiting in England for concerts to meet Toynbee and converse with him. They would meet again many times thereafter; in England when Eugene gave concerts and in America when Toynbee gave lectures. A deep friendship was established, sustained by often heated discussions, and continued until Toynbee’s death in 1975.

Toynbee contributed towards reinforcing Istomin’s pessimistic view of the evolution of Western civilization and its inexorable decline. Istomin became more and more convinced that the democratic system, to which he was so attached, was gradually losing its ideals and requirements. Citizens no longer felt the need to deal with challenges other than their own material ones. Creative minorities were no longer in a position to play their role. Democracy was becoming a race to the bottom.

For Istomin, it was clear that the ongoing evolution of our civilization was questioning the very existence of human beings: “Human kind is the elite of nature, and it seems to me that we are not progressing very well. I am responsible for this situation, we are all responsible. We are approaching a time when we are threatened either by the destruction of the planet or by a radical change in human nature. To preserve humanity, we should be deprived of our power of aggression. But if we take away our capacity for aggression, we also take away our capacity for creation! We will no longer be human beings – we will no longer be the elite of the planet. That’s what’s happening in art. Now we consider that everything is equal, Mozart and Elvis Presley, Pop Art and Rubens. This is the consequence of egalitarian revolutions. But we forget that even if there is democracy, political equality, each citizen has the duty to rise, humanly, as high as he can, to be in a way an elite.”

Here are some passages from the text Arnold Toynbee wrote in 1968 for the 25th anniversary of Eugene Istomin’s career.

“Eugene is a dedicated practitioner of his art, but he is a human being first, as all of us ought to be (though many of us are not), whatever vocation we happen to follow. Eugene’s capacity for friendship is one of his notable characteristics; the breadth of his interests is another. Whenever we meet, we rush into exchanging views about current world affairs, about history, about life. These conversations are usually lively. I have the impression that Eugene enjoys them as much as I do. As it happens, we do not see at all eye to eye on some of the most controversial international issues of our time, and we declare our conflicting opinions frankly and sometimes combatively. We can afford to differ on impersonal questions because we are quite sure of our personal relations with each other.”

Toynbee also mentioned the importance of his Russian roots and how America and music made him a citizen of the world.

“The experience of being a refugee is a crucial test of character. If it does not break you, it may make you. I can think of several distinguished friends of mine, besides Eugene, who have in their family background, the experiences that Eugene and his family have. If you rise superior to the ordeal of being transplanted, you are likely to distinguish yourself in whatever may be your chosen walk of life.

For striking fresh roots, America is favorable soil. One of the sources of America’s greatness is that, generation after generation, she has given new hope and new openings to incomers from the Old World who, in their original homes, would not have had the chance that they have been given in America and that they have seized there by their own prowess. Eugene is a member of that long series of eminent citizens whom the United States has gained by her traditional hospitality. Eugene is staunchly American, but his case is one of those happy ones in which America’s gain is not his ancestral country’s loss; for music is a supra-national art. In our all too nationalistic-minded present-day world, musicians are members of the slowly growing company of world citizens. Musicians are welcome everywhere, so in all countries they find themselves at home.”