Istomin’s first meeting with Nixon was quite disconcerting. It took place in 1958 at the Casals Festival in Puerto Rico. Since 1952, Nixon had been Eisenhower’s vice-president. He landed with his official plane at San Juan Airport, after a very agitated tour in South America, where he had had to face violent student demonstrations in Lima and especially in Carácas. Istomin went together with Henry Raymont, the distinguished journalist, to greet him. He was stunned to find out that Nixon was not interested in hearing either Casals or any other great musician of the festival, but that he had only come to hear his friend Chu-Chu, the distinguished Puerto Rican pianist Jesús MarÍa Sanromá, who was also taking part in the festival.

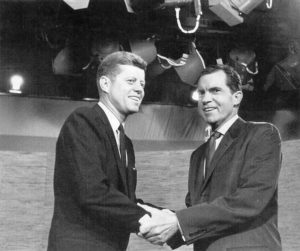

In 1960, Istomin had passionately supported Kennedy against Nixon, even in the post-concert receptions, and this brought him reproaches from his management and resulted in him never being re-invited to some Republican strongholds. After a long time in the political wilderness, Nixon was nominated as the Republican candidate for the Presidential election of 1968. At that time, Istomin was still more involved in supporting the Democrat candidate, Hubert Humphrey, to whom he was quite close, both as a man and as a politician. Under difficult circumstances, he assumed leadership of the Arts and Letters Committee for Humphrey.

The war in Vietnam was front and center of the debates. Peace negotiations had begun in Paris in May 1968 and turned out to be positive in late October. Johnson had decided to stop bombing and the North Vietnamese had agreed that a South Vietnamese delegation take part in the discussions. The success of the negotiations would have certainly meant a victory for Humphrey and the Democratic camp in the impending elections, but Nixon, probably assisted by Henry Kissinger, sabotaged the process by persuading the South Vietnamese president, General Nguyễn Văn Thiệu, not to appear. Nixon had convinced Thiệu that a Republican America would be much more favorable to him than a Democratic one. It was treason of the highest interests of his country, confirmed by the phone tapping of his discussions with his closest advisors. This allowed Nixon to be elected very narrowly. With Nixon and Kissinger in power, the war continued for five years, and for two more years with only the Vietnamese. This additional time was accountable for several hundreds of thousands of deaths.

In 1972, when Nixon ran again for the Presidential election with a new secret plan to make peace in Vietnam, It was clear in Istomin’s mind that Nixon was absolutely not to be trusted. For the first and only time in his life, he did not exercise his right to vote, as he thought that George McGovern, the candidate the Democratic Party had preferred to Humphrey, was demagogic and unreliable.