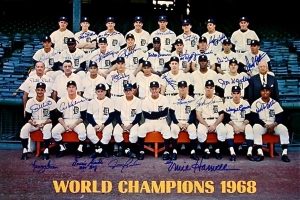

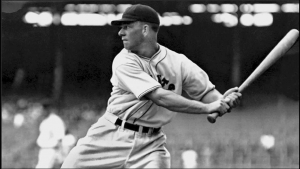

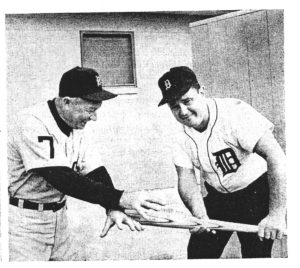

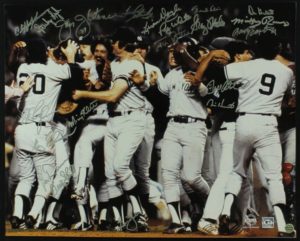

Istomin revealing the mysteries of the Schumann Concerto to players of the Detroit Tigers

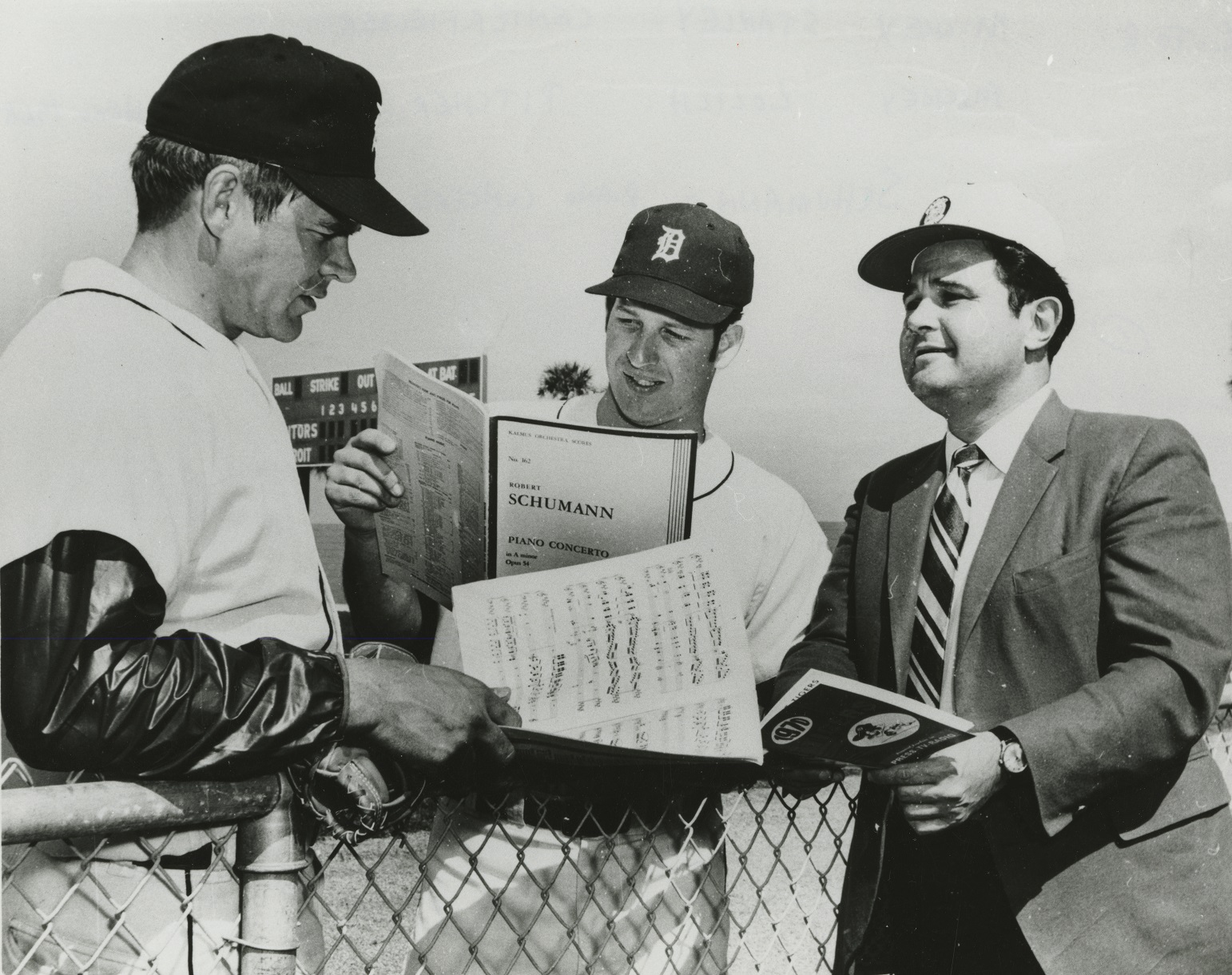

Istomin’s passion for baseball was largely echoed in the press. Current Biography said that “for a short time he was a bat boy for the Brooklyn Dodgers”. Time Magazine gave a less glorious account: “Brooklyn-born Eugene Istomin abandoned a boyhood ambition to play for the Dodgers (he served as their water boy during one spring training) in favor of a scholarship at Curtis, where he studied under Pianist Rudolf Serkin.” In 1968, the musicologist Frank Hruby interviewed him for the Cleveland Press and titled his article “Istomin – Philosopher, Pianist and Tiger Fan”. In The Bulletin dated September 21, 1980, James Felton wrote: “They call him ‘Fingers’ Istomin – the art expert and concert pianist. (…) Though he’s spent most of his life involved in art, he had such a mania for baseball that he once moved his piano to the Florida spring training for the Detroit Tigers, who nicknamed him ‘Fingers’.”

His passion for baseball started in early childhood. It allowed him to feel integrated with his peers, without which he might have remained confined in the gilded cage of being a child prodigy. In his own words, baseball was Istomin’s “passport to America”.

Thanks to Doc Greene, a journalist of The Detroit News, Istomin was allowed entrance into the impenetrable secrets of baseball. His mentor was Chuck Dressen, a baseball legend who ended his career as manager of the Detroit Tigers, the team he brought back from the lowest ranks to the top. Through him, Istomin soon learned the ropes of this extremely complex sport.

Whenever he could, he went to the stadium to see the games, and he tried to arrange his schedule each spring to visit the Florida training camp of the Detroit Tigers. The baseball world welcomed him as one of its family. He was considered a VIP and was graciously invited everywhere, even if few managers, and even fewer players, were interested in the piano.

His passion for this sport did not distract Istomin from his principles of humanism. He was shocked by the way the players were treated. They were like slaves – albeit well paid -but still slaves who were shamelessly exploited. When they were no longer profitable or less competitive due to age or injury, they were gotten rid of. They could also be sold to another franchise, even against their will. Istomin often protested against such methods and claimed that baseball would considerably benefit from more humane conduct: a higher commitment from the players, who would be more attached to their club, a better quality of playing thanks to a steadier squad, and greater loyalty from their fans.

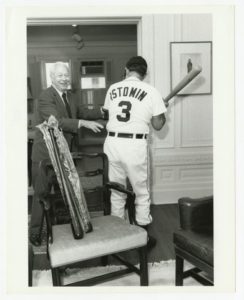

In 1987, when Istomin received the Paul Hume Award (named after the famous critic of the Washington Post), the Detroit Tigers presented him with a genuine Tigers’ uniform, tailor-made with his favorite number and his name on the back, and a personalized bat. He was also proposed an American League player’s contract, with an hourly wage of $3.87, for teaching the piano to the complete team!

When he could not go to the stadium, Istomin watched baseball on television, in his hotel room or at home. Emanuel Ax remembers that it was inconceivable to begin a class before the game had ended. Istomin admitted that if he had spent the thousands of hours he had been watching baseball at the piano instead, it would have allowed him to add a few Beethoven sonatas and Mozart concertos to his repertoire. He told James Gollin: “The only waste of time in my life was baseball”. But he harbored no regrets, because for him baseball was an absolute pleasure.

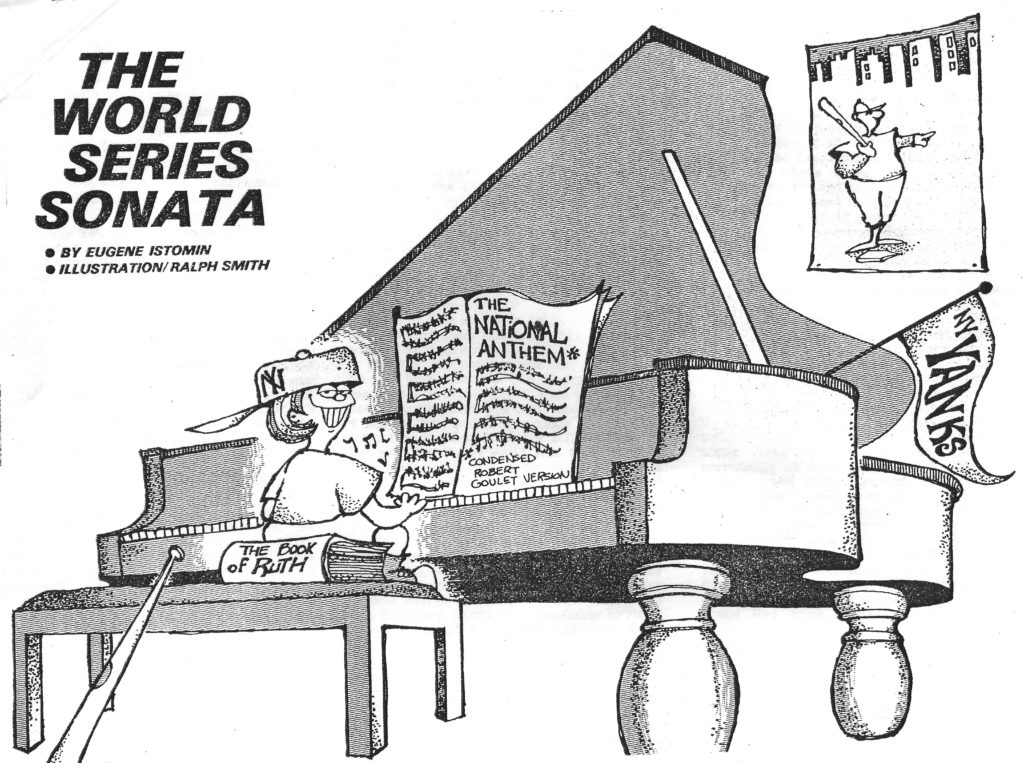

A funny self-interview of Istomin was published in various newspapers in October 1977. It was entitled either “The World Series Sonata” or “Prodigy Eugene Istomin was a normal kid, thanks to baseball”. There was a quote in large letters – “Istomin: Musician is no softy; he’s tougher than pro athlete”. It was signed Eugene Istomin, New York Times Service. In it, he recounted the full story of his passion for baseball. It is also a valuable record of his writing replete with humor and self-mockery, with a mischievous split personality between Istomin, the reasonable pianist, and Fingers, his alter-ego baseball fan, as inspired by Schumann’s Eusebius and Florestan!

Istomin: You are a well-known and, I’m told, respected musician. When and why did you become a baseball nut?

Fingers: My first piano teacher ordered me to become a normal kid.

I: Elucidate.

F: When I was six years old, my parents took me to play for Alexander Siloti, a magnificent, huge old Brahman Russian émigré musician who was a favorite pupil of Franz Liszt and Tschaikovsky; he was also the uncle and intimate of Sergei Rachmaninoff. I tapped out some “by ear” accompaniments to my mother’s singing of Russian songs. When we finished he got up and grabbed his left foot and wrapped it around his right ear, leering and bellowing: “And what do you think of this, my boy?” Then he said to my father: “Child prodigies are a bane, a crime against nature, and if you intend to exploit this boy, I will ask you to leave immediately”. My father quietly answered: “We are prepared to make every sacrifice except to exploit our son”. Siloti’s voice softened: “Then you will let the boy grow up as normally as possible under abnormal circumstances. The life of a concert pianist is grueling; he will need stamina, so I want him to take up sports. Let him play ball.” So that’s the way it was.

I: Your father was a race-horse owner in Russia and even bought and ran a horse named Petrograd at Aqueduct in the 1950’s. (He won). I take it baseball was not his thing. Who took you to your first major league baseball game?

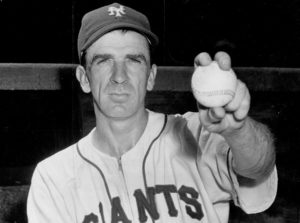

F: My uncle Elias, a bachelor and C.C.N.Y. graduate who loved books, girls and winning at anything. He invariably got tickets for all the big games. I saw the Giants murder the Dodgers in a double-header in 1933 – it was my first baseball spectacle. Later on, in 1939, I was at the All Star Game at the Polo Grounds when Carl Hubbell struck out Ruth, Gehrig, Foxx, Simmons and Cronin in a row. That September I watched the Giant-Cardinal double header when, late in the second game, Cardinal manager Frankie Frisch procrastinated, waiting for darkness before bringing in Dizzy Dean to stop the Giants and go on to win the pennant. A few days earlier, I had seen the Dean brothers, Paul and Diz, pitch back-to-back shutouts in a doubleheader against the Dodgers, 13 to 0, and 3 to 0, with Paul pitching a no hitter. It was the first of seven I have seen up to now.

I: The Giants won the pennant and championship in 1933. I take it you became a Giant fan.

F: God forbid; I became a Dodger fan. I knew the agony and the ecstasy. Real Dodger fans were spawned in the 30s, when the team spent the Depression in sixth and seventh place. When they started winning, it was the first successful revolution since 1776.

I: Wait a minute. Everyone knows you are a Detroit Tiger fanatic. Don’t you go every year to the Tiger spring training camp?

F: It’s obvious you don’t understand love, hate, obsession. One of my uncle Elias’ big games in 1934 was a Yankee-Tiger doubleheader. Already a confirmed Dodger fan, I had to like underdogs, which the Yankees were not. The Tigers could beat them; in fact, they managed to win three pennants between 1934 and 1940 during the Yankee imperial history. They are MY TEAM today.

I: Did you play baseball yourself? Did you dare?

F: I not only “dared” to play, but also spent hours and hours throwing baseballs and even tennis balls through a hoop to perfect my control. I pitched hundreds of Dodger victories against everybody except Detroit. Frisch, Mel Ott, Bill Terry, Ducky Medwich, Gabby Hartnett and other great hitters fell into their worst slumps against me. In real games in Central Park and Riverside Park I found hardball play generally less damaging to my hands than softball. By the way, piano playing is even harder on the fingers.

I: Never mind about the fingers, Fingers. It sounds as if you weren’t practicing much, except in left field.

F: So true. Every hour I was forced to practice the piano I could have been perfecting my hitting to the opposite field.

I: Did you intend to become a ballplayer?

F: Not at all. Siloti wanted me to have fun, so I had fun. I admit I got a bit carried away, but what’s wrong with watching Joe DiMaggio by day and hearing Rachmaninoff by night? I finally found time for practicing when I got to be about 13 years old – that was what old Siloti had planned all along.

I: But this addiction. How do you explain it?

F: I liked being a boy. Being good at sports gave me a cover to mask my being a “little genius”. It made me a regular boy with my pals. Through baseball I ceased being an émigré child and became an American kid.

I: How did you get into what is known, capitally, as the Sports World?

F: I am not in it, but I am a graciously invited guest. In 1964, Doc Greene, columnist on the Detroit News, and his wife asked me to be their house guest, so that I could get away from the rat race of the New York music scene. I would occasionally drop in at the Detroit Symphony concerts and drag soloists and conductors back to the Greenes’. One night, we gave a party for pianist Leon Fleisher and Sixten Ehrling, then conductor of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Doc decided to spring on me a real-life baseball character. He was 340 pound Red Jones, retired American League umpire, who had great wit and a dubious familiarity with the names of people in classical music. He promptly christened Fleisher “Lenny Baby”, Ehrling “Sixtoon” and me “Fingers”. It was love at first sight between Redsie and me. He didn’t laugh at my baseball comments, and I reveled in his every anecdote of diamond life, like the time he chased the entire Chicago White Sox team off the bench during a game with Boston.

I: Does Red Jones like music?

F: ‘’Turkey in the Straw”, “Come to Jesus”, the race-track bugle call.

I: What happened then?

F: Charley Dressen, the old Dodger, was managing the Detroit Tigers at the time. He had a penchant for the ponies. A master at ploys, he appointed Red Jones to place his bets. Charley, at once, took a shine to me. Off the field when Tiger business was over, he spoke about baseball only to me – what an education that was! He started taking me to dinner with Jim Campbell, the Tiger’s general manager, and through Charley and Jim, the whole Tiger organization, from owner John Fetzer down, became my family. Campbell remains doubtful about some trades I tried to get him to make. In the mid-60s I figured out a legal way to get Sandy Koufax without giving up anybody. This idea was considered radical and I was voted down. I retain the formula for this gambit for possible future use.

I: Judging from one of your photographs, you must have tried to sign Pablo Casals for Tigers. How did you railroad him into the pose?

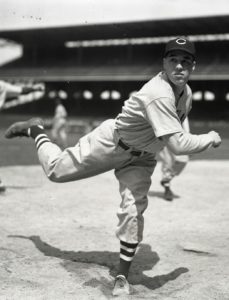

F: Casals was a fine tennis player and sports fan in general. He enjoyed watching baseball on television but kept saying, “Beautiful! I don’t understand anything.” Like most Europeans who prefer perpetual-motion sports, he found baseball rules harder to grasp than the theory of relativity. I could have straightened him out at his first ball game in 1901, which unfortunately preceded me by a year or two. As you can see, he was a natural hurler like me.

I: Your friends Lee McPhail and Frankie Frisch weren’t Tigers.

F: Lee McPhail, a concertgoer, who was general manager of the Yankees, finally gave up trying to lure me to them and, in despair, became the American League president. Meanwhile, I gave my approval for Ralph Houk to leave the Yankees and manage Detroit. Frankie Frisch was a baseball manager I could talk music with – at last. How he loved music! The 1968 World Series was a repeat of the 1934 Tiger-Gas House Gang Series. The seventh game in St. Louis had Bob Gibson pitching against Mickey Lolich. Where was Frisch? Sitting in an armchair next to me, supine, like a boxer before a fight, watching television in my apartment in New York. He had come to hear me play a Beethoven concerto that night with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. Like all class professionals, he hid his regret when the Tigers squeaked out their glorious 4-to-1 victory. “I’m glad for you, Eugene,” he said in his high-pitched voice. “Now go and play BEYOOTIFUL for the old Flash.”

I: Did you ever get Dressen to a concert of yours?

F: Yes, poor Charley went to two concerts in Detroit a couple of weeks before he died, but I’m sure this did not hasten his departure. I had prepared him for the rigors of music earlier by having a piano sent to the Tiger spring-training camp for my annual visit. There he heard me practicing often. Once I played a Chopin etude and he later reported to the general manager Jim Campbell, “The kid can really play it!” So you see, Frisch and Dressen, rough contentious men on the playing field, were softies underneath it all. So are the other sports people.

I: What do you mean? Aren’t musicians softies?

F: That’s what you think. They are 10 times tougher, more disciplined, and self-centered than professional athletes. Maybe they have to be.

I: Why? Isn’t the pursuit of excellence in all things basically the same?

F: In case you’ve forgotten, there is a difference between playing a Beethoven sonata and hitting a home run! A home run is a home run, the absolute maximum that a batter can do; no one can revise it, refute it, or change the effect of its impact, no matter how it was hit. A writer does not “review” a home run; he “reports” it. Right? Now what about the Beethoven sonata? Who gives an artist’s performance its precise value? The artist? Critics? Public? The arts have no scoring system – thank heaven. Everyone is an umpire and the toughest is the artist himself, if he is any good.

I: Uh, hunh. This is heavy stuff. Speaking again of Charley Dressen, where were you when Bobby Thomson hit his unreviewable home run?

F: I was sitting in Pablo Casals’ living room in Prades at the foot of the French Pyrenees listening to the U.S.A.F. radio broadcast. When the holocaust struck, I jumped out of my seat, and stood transfixed before the nonplussed Casals while Russ Hodges’s voice screamed over and over, “The Giants win the pennant”. “What happened, my boy?” said Casals.”A most catastrophic and magnificent thing”, I replied. A sporting event had reached the zenith of tragedy and sublimity, as in a great work of art. I learned to weep for winners as well as losers after that game.

I: What did Dressen tell you about it?

F: He said, “We got beat”.

I: Sounds like a loquacious musician.

F: It’s the sport’s version of Flaubert’s ‘le mot juste’.

I: What were manager Mayo Smith’s immortal words to you when Denny McLain, his ace pitcher, stubbed his toe and failed to win a single game for the Tigers down the stretch in 1967, costing the pennant?

F: “Maestro, what the hell I do now?” I answered, “Win it all next year”. He did.

I: And Dressen after this disaster?

F: Charley bounced back and won the next two pennants with a great Dodger club.

I: The Giants were an Inspired team in 1951.

F: Inspired is right, but the Dodgers were better and they blew It. I feel they were even a tiny bit better than the Stengel Yankees who had to go to seven games to beat them three out of four times during 1952 and 1956. Clutch performance is all important in big games; the Yankees have been past masters at that. It finally took Johnny Podres’s change-ups and an unlikely catch by Sandy Amoros on Yogi Berra in 1955 to win the World Series for the Dodger under Walt Alston. They have been hard to beat ever since.

I: Speaking of Dodgers, Yankees, Tigers and Fingers, what does your wife think of all these shenanigans?

F: Our wife, you mean (you lucky fellow). She loves baseball because she played and watched it as a child in Puerto Rico. Now she’s becoming a diamond egghead, what with all our friends in the game.

I: A beautiful egghead, I may add… What is the most artistic moment in a baseball game?

F: There are many. A Graig Nettles or Brooks Robinson making one of their patented miracles at third base. A Lou Brock or Maury Wills bunting their way on, then nipping a split-second on a wary pitcher’s motion and stealing another base. Or an Al Kaline cutting off an extra-base hit in the right field corner and rifling a perfect throw to third, catching a runner daring to come on from first. Or the Willie Mays masterpiece in center field. My favorite scene, though, is pitcher versus power hitter in the clutch. This a bloodless bullfight. All really good hitters love the fast ball, no matter what the velocity. Pitchers like Bob Feller and Nollan Ryan could surpass the speed of sound, but the DiMaggios and Rod Carews could see the stitches on an incoming fast ball. A pitcher’s only hope with that kind of hitter is to upset his timing with sneaky breaking stuff, but in precisely the right spot, otherwise it’s curtains again.

I: You mean the pitcher must try to make the perfect pitch in the moment of greatest danger, not just to overpower? Like the eloquently played but simple sounding Mozart phrase next to the crashing octaves of Liszt?

F: It’s harder to play Mozart when the adrenal is flowing than to rip off a fast fortissimo passage. It takes courage to thread the needle while the boat rocks between Scylla and Charybdis.

I: You’re mixing metaphors, but let me add that Hemingway called it grace under pressure.

F: A good example was in a Yankee-Detroit game, some years ago, in Tiger Stadium, a hitter’s ballpark. In the bottom of the ninth, with men on base, in a tight game, the great lefty Whitey Ford faced Willie Horton, a pretty formidable right-handed hitter. Whitey threw only three pitches. They were all slow breaking strikes and Horton never took the bat off his shoulder -blinking in disbelief. It was like Manolete on his knees with his back to the bull, three times in a row.

I: Ted Williams said that the single most difficult thing in sports was hitting a baseball off major league pitching.

F: Maybe, but when the heat is on, it is getting Ted Williams out that is the greater achievement. The clutch in Cincinnati is getting Joe Morgan or Pete Rose out when the game is at stake.

I: Many baseball people say that today’s athletes are bigger, stronger, and defensively more formidable than those of yesteryear because of emphasis on relief pitching and more efficient fielders’ gloves. Do you agree?

F: I don’t know, and no one ever will, but I shudder to think of trying to hit a ball through Marty (the Octopus) Marion of the Cardinals with the oversize glove of today – or Phil Rizzuto or Charlie Gehringer at second base in his prime. They would have reduced the necessity of four infielders to three, and the commissioner would have banned them. As for relief pitchers, the good and the bad hitters hit them just as well or poorly as the starters. Still, gloves and relief pitchers aside, no team I have ever seen has been as devastating as the New York Yankees of Joe McCarthy between 1936 and 1939. Some Stengel Yankees came close. If they had reliable pitching, the Cincinnati Reds would win today. McCarthy’s Yankees lost a total of three games in four successive World Series!

I: You sound like a luddyduddy music critic pining for piano playing’s golden era of the 1920’s. Since baseball was without black players, how can you say it was better than today?

F: Well, do you think piano playing has improved that much?, As for the exclusion of black and Lain-American players, just imagine what it would have been like, in the great old days, with them. What would baseball today be without them? The white ball players’ statistics would pale (ho,ho) next to the prewar boys. Eh, what?

I: What’s wrong with John Bench, Carl Yastrzemski, Steve Carlton, Don Sutton, et al.?

F: Listen, they are great. I love all players – even the .190 hitters – but once you name the limited number of superstars, I see far fewer reliable pros. Where are the Doc Cramers, Wally Moseses, the Joe and Terry Moores? They would be two-million-dollar ballplayers today. O.K., Johnny Bench is a genius, and Thurman Munson and Carlton Fisk are also top catchers. But are they better than Mickey Cochrane, Bill Dickey, Gabby Hartnett, Rick Ferrell, Spud Davis, Gus Mancuso, Ernie Lombardi, all in one era? Come on, it’s no contest. Greats are greats in every period. But today, I wish my friend Danny Kaye had the 1938 Newark farm club of the Yankees to start his new franchise in Seattle. They would be instant contenders.

I: Stop knocking expansion teams. I am rooting for them, especially Danny’s.

F: So am I, but a lot of kids with great talent are playing in the major leagues before they are ready. It’s like learning the piano concerto repertory as a youngster with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall. It’s great, I know, I did just that when I was a boy, but there is no substitute for experience, self-discipline, and practice, and more practice learning your art. Some kids in baseball are ruined by premature stardom just as they can be in the concert world. How many youngsters can be relied upon to lay down a sacrifice bunt? It’s healthier and more profitable for the team than striking out trying for nine home runs a year. The main point, even for the greatest, is “I can and must do better than the last time”. There is always a way. Both million-dollar ballplayers and musicians can have a tough time with the screwball of success. Catfish Hunter was the top pitcher for years at Oakland until he became a millionaire. On the other hand, Vladimir Horowitz has been the highest-paid pianist for 30 years and he still gets better. Few superstars in sports can match this.

I: Not many pianists either.

F: Never you mind! Catfish will return to form. If the Yankees give up on him, I’ll take him in Detroit.

I: That’s awfully nice of you. Athletes don’t have 30 years to develop.

F: Of course not, but aren’t we talking about people who start at the top getting better? The only alternative is to get worse. “My best yesterday is not enough today,” that’s what you have to feel.

I: Who in any profession says that?

F: That is what life is. Learning and trying to get the most out of yourself, what else is there?

I: This coming World Series promises to be exciting. The National League has dominated baseball for a long time. What will happen?

F: No one is going to win this one in four games, not like last year. It will probably go the limit. I think that the Yankees are the only American League team that can win over Philadelphia or Los Angeles, both powerful and balanced clubs. The Red Sox and Orioles, although inspired, were too thin, and Kansas City’s series inexperience would probably beat them.

I: Hang on! What makes you think that the Yankees will beat Kansas City in the playoff?

F: Listen, I know the odds. Kansas City probably has a 5-to-4 edge because they can play three out of five games at home -unlike last year, when Chris Chambliss’s bottom-of the-ninth, fifth-game homer saved the Yankees. This year, it could well be John Mayberry in the same spot in Kansas City. But what’s the point of this interview? You want an expert opinion? I pick the Yankees. The American League has the home team advantage this year with four out of the seven possible games. This is crucial if the series goes beyond five games.

I: You’re exaggerating the home team advantage, aren’t you?

F: Baseball is the only sport in which the “last shot” is the privilege by regulation of the home team. In any other contest, the edge is psychological. Here it is structural. What could be more telling?

I: The first pistol shot in a duel, perhaps?

F: Oh, la, la!

I: Get back to the Yankees.

F: Their pitching is deep and solid, their infield brilliant, the outfield is only fair defensively, especially without Paul Blair; but the catching is excellent. Offensively, however, this is a top ball club. I don’t think that anyone will keep Mickey Rivers off the bases as Cincinnati did last year. When the series returns to New York for the denouement, Nettles or Chambliss or Munson, Piniella, Reggie Jackson, or someone else will put a lump in the throat of the National League in the late innings. The lights will glare brilliantly over Yankee Stadium. Some 55,000 people will stand in anticipation of the electrifying moment. Paper will fall from the bleachers in the din. The aura of a baseball field in crisis – a festive fan of green and brown trembling with players and umpires coil-crouched in tension. I love that scene. How can anyone tire of such a moment? On the Tiger Stadium next year!

I: May I suggest we get back to the piano?

F: Both of us?

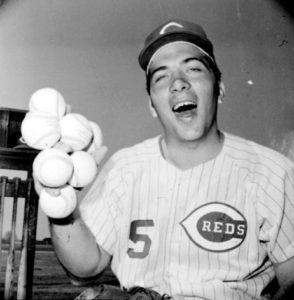

Joe DiMaggio