Eugene Istomin used to say: “If you can play Mozart, you can play the entire repertoire”.

When asked to speak about Beethoven or Schumann, Istomin could talk forever. About Schubert and Chopin, he would have to search for words – but regarding Mozart, he often could not find any. He could only enlighten the way he played certain passages by referring to some of the opera arias. For him, Mozart was self-evident and embodied the very essence of music, making it impossible to explain him with words. He could not be copied or imitated. Istomin remarked that every great pianist who wrote cadenzas for Mozart’s concertos attempted in vain to write them in the style of the composer, and had to resort to composing them in the style of Beethoven. Mozart held a very important place in Istomin’s career.

The Concertos

In addition to the Concerto for 2 Pianos which he played only on special occasions (with Serkin, Fleisher and Pommier), his repertoire included five Mozart concertos.

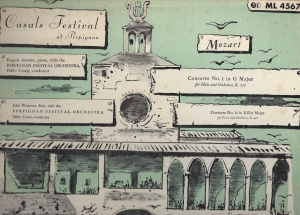

The Concerto No. 14 in E flat major, K. 449 was the first concerto he performed. It was in Boston in the spring of 1943 with a youth orchestra. He subsequently played it frequently with Adolf Busch during their first tour in 1944, in alternation with the Bach Concerto BWV 1052. When he was invited to the second Prades Festival in 1951 (which actually took place in Perpignan), Istomin was also asked to play and record the Concerto K. 449 with Casals. There were five other Mozart concertos during the festival, with a dream cast: Clara Haskil in the K. 459, Myra Hess K. 271, Mieczyslaw Horszowski K. 595, Yvonne Lefébure K. 466 and Rudolf Serkin in the K. 488. The Perpignan daily newspaper L’Indépendant reported that Istomin received tremendous acclaim and was obliged to make endless curtain calls! Howard Taubman, the New York Times special correspondent, was captivated by Istomin’s “restrained, subtle and joyous reading of the piano part in the E flat Concerto.” On July 29 he wrote about Istomin: “His growth in the past few years, as proved by his share in the evenings of Beethoven trios and his work as a soloist in Mozart’s E flat Concerto K. 449 has been astonishing… he is on the way to becoming one of our major pianists.”

The Concerto No. 14 in E flat major, K. 449 was the first concerto he performed. It was in Boston in the spring of 1943 with a youth orchestra. He subsequently played it frequently with Adolf Busch during their first tour in 1944, in alternation with the Bach Concerto BWV 1052. When he was invited to the second Prades Festival in 1951 (which actually took place in Perpignan), Istomin was also asked to play and record the Concerto K. 449 with Casals. There were five other Mozart concertos during the festival, with a dream cast: Clara Haskil in the K. 459, Myra Hess K. 271, Mieczyslaw Horszowski K. 595, Yvonne Lefébure K. 466 and Rudolf Serkin in the K. 488. The Perpignan daily newspaper L’Indépendant reported that Istomin received tremendous acclaim and was obliged to make endless curtain calls! Howard Taubman, the New York Times special correspondent, was captivated by Istomin’s “restrained, subtle and joyous reading of the piano part in the E flat Concerto.” On July 29 he wrote about Istomin: “His growth in the past few years, as proved by his share in the evenings of Beethoven trios and his work as a soloist in Mozart’s E flat Concerto K. 449 has been astonishing… he is on the way to becoming one of our major pianists.”

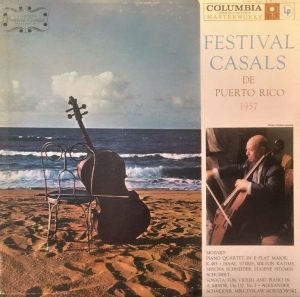

In 1945, during his second tour with Busch, Istomin added two new concertos by Mozart: No. 12 in A major K. 414, which he played very rarely afterward, and No. 9 in E flat major, the K. 271, which he kept in his repertoire until the very end of his career and which remained his personal favourite. He was so frightened by the K. 271 that he postponed his first performance several times until Busch ultimately refused to change the program yet again and pushed him onstage! Istomin considered it to be the most difficult concerto of all, both technically and musically. In spite of its early composition, it unveils all the depths of Mozart’s imagination and soul. Istomin was especially moved by the slow movement, the achingly poignant Andantino. He was amazed by the incredible imagination of the finale, which has no equivalent in any later concerto, and by the omnipresence of the piano from beginning to end, with the feeling that the piano is Mozart himself. For Istomin, performing this concerto was a very unique combination of stress and enjoyment! He performed it under great conductors with very different personalities: George Szell, Leopold Stokowski, Alexander Schneider, Fritz Reiner, Georg Solti… but he deeply regretted that the scheduled performance and recording with Casals at the 1957 Puerto Rico Festival was cancelled, due to Casals’ heart attack. The main document of Istomin playing this concerto is a video made by French Television in 1972, with Alexander Schneider and the Chamber Orchestra of the ORTF.

Istomin performed the Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491 for the first time in 1962, under Milton Katims at the Seattle World Fair. When asked by Richard Freed about this concerto, Istomin noted that “the whole of K. 491 is related to ‘wrong notes’. In the outer movements, minor scales turn major and return to minor, and in general Mozart enjoys the play of the minor second, as well as his extension at the fifth that Beethoven liked to point out – here a half-step higher, there a half step lower…” Istomin also mentioned how amazed he was by the end of the boldly dramatic first movement which “waltzes to a close.” The cadenza he played in the first movement included contributions from Claude Frank, Leopold Mannes and himself.

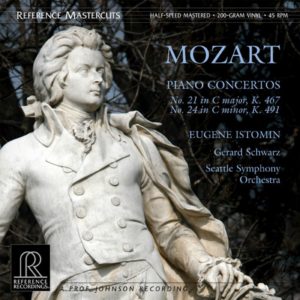

As for the Concerto No. 21 in C major, K. 467, Istomin tackled it in 1976 and it henceforth became the Mozart concerto he performed most often. He told Richard Freed that “a characteristic feature of this masterpiece is the use of clichés to make miracles. There is a sense of personal renewal here – something you know is going to happen, and when it does it is deliciously surprising, fresh, eternal…”. He wrote a cadenza for the first movement but later on, he played an amalgam of his own and Badura-Skoda’s. He used Lillian Kallir’s cadenza for the finale. Istomin recorded these two concertos in 1995 with Gerard Schwarz and the Seattle Symphony in only one session.

As for the Concerto No. 21 in C major, K. 467, Istomin tackled it in 1976 and it henceforth became the Mozart concerto he performed most often. He told Richard Freed that “a characteristic feature of this masterpiece is the use of clichés to make miracles. There is a sense of personal renewal here – something you know is going to happen, and when it does it is deliciously surprising, fresh, eternal…”. He wrote a cadenza for the first movement but later on, he played an amalgam of his own and Badura-Skoda’s. He used Lillian Kallir’s cadenza for the finale. Istomin recorded these two concertos in 1995 with Gerard Schwarz and the Seattle Symphony in only one session.

Istomin had often thought about other concertos. The program flyer of the 1953 Prades Festival announced that he was to play the Mozart Concerto No. 25 K. 503 under Casals. He had even written a cadenza (which Fleisher would eventually use and arrange for himself), but in the end, he did not feel ready and asked Casals to play Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto instead. Istomin also dreamed of playing the Concerto No. 23 in A Major but never tackled it, without being able to explain why. However, he ruled out playing certain concertos which, in his mind, “belonged” to pianists whom he admired and loved: No. 17 K. 451 was Kapell’s, No. 19 K. 459 and No. 20 K. 466 Haskil’s, No. 22 K. 488 Serkin’s, and No. 27 K. 595 Horszowski’s.

Chamber music and solo piano

Unfortunately, the Trios are not among the peaks of Mozart’s work, and most of them are not appropriate for performance in large concert halls. Cortot, Thibaud and Casals only performed the Trio K. 542 (twice) and the Trio K. 564 (once). Istomin, Stern and Rose chose a more brilliant one, the Trio in B flat major, K. 502. Its piano part is more like a concerto, even if the strings do have occasional opportunities to shine. They played it often from 1975 and recorded it for Columbia. However, the tape was unexpectedly lost, and the only remaining document is a video recording.

As for Mozart’s two piano quartets, K. 478 in G minor and K. 493 in E flat major, Istomin considered them to be true masterpieces, worthy of the greatest concertos composed at the same time. Unfortunately, piano quartets are very difficult to schedule during regular seasons, as they require a festival or other special circumstances in order to bring the musicians together and allow them time to rehearse. Istomin performed each of them about ten times, especially at the Puerto Rico and Israel festivals, with prestigious colleagues like the Budapest Quartet, Stern, Rose or Schneider, as well as with talented young musicians in Marlboro and Evian.

Most great pianists are reluctant to perform Mozart’s works for piano solo. Istomin was not, and he frequently performed the K. 394 and K. 397 Fantasies, the Rondo K. 485 and three Sonatas. The first one he performed in the late 40s was the Sonata in C K. 330. From 1950 this was replaced by the Sonata in D K. 576, which he liked immensely and found diabolically difficult: it was so easy to rush in the fast outer movements, making it extremely challenging to remain in control! According to Istomin, its three movements seemed to paint a portrait of Mozart as a musician and as a man: the perfect structure and counterpoint of the first movement, the tenderness and melancholy in the Adagio, and the exuberance of the Finale. Disregarding the openly dramatic sonatas (K. 310 and K. 457), he became fond of the unpretentious early Sonata in G major K. 283, which he programmed regularly from 1989, revelling in its charm and freshness and in its inventive pianistic technique with left hand octaves and brilliant crossed-hand passagework.

Interviews by Bernard Meillat in 1987, 1991, and 1997

Music

Mozart, Concerto No. 9 in E flat major K. 271. Eugene Istomin, ORTF Chamber Orchestra, Alexander Schneider. Live recording at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on January 28, 1972

.

Mozart, Quartet for Piano and Strings in E flat major K. 493. Eugene Istomin, piano. Aaron Serofsky, violin. Dov Scheidlin, viola. Eric Gaenslen, cello (students of the Juilliard School). Evian, May 31, 1992