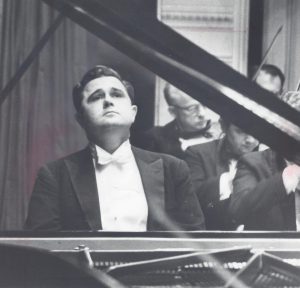

“An artist of decided reticence, and even mystery. Solitary, serious, and of a brooding Beethovenesque disposition”. This is how James Gruen opened his long portrait of Istomin in the New York Times on November 22, 1971. The resemblance of Istomin to Beethoven struck many of his interviewers and people he met. This familiarity did not stop at appearances. Both shared the refusal to compromise and an irrepressible need to say what they thought and to revolt against injustice, regardless of the subsequent consequences. Beethoven was the composer with whom Istomin most readily identified, touched by the combination of strength and vulnerability he also felt within himself. Beethoven’s music helped Istomin to maintain his faith in humanity despite the tragedies and disappointments of the 20th century. Istomin’s career traced a long journey together with Beethoven’s works. This article follows his path, documented by interviews which he gave in 1987 and 1991. It successively brings up the concertos (in the sequence in which he approached them), followed by the works for piano solo and chamber music.

The Fourth Piano Concerto

“This concerto is among the richest nutrients for the spirit, mind and soul. For me, it is one of the absolute masterpieces of human creation. It belongs to the five or six peaks in the entire history of art, all disciplines included. It is the concerto I have played most often throughout my career, perhaps five hundred times. It is also the one in which I have the strongest feeling that I have something very personal to say.

Of course, there is the Promethean cadenza of the first movement, which is a fantastic challenge for the pianist, one of the highest achievements of all piano music. But there is also the incredible Andante with its deeply intense dialogue between the piano and the orchestra. The other Beethoven concertos can be played with a good conductor, but for this one you need a great one, with whom you can really get along. Otherwise it can be very frustrating. I had many difficult experiences!

For some people, there is an allegory or parable, with at least some programmatic intentions in this movement. The most common idea is the story of Orpheus and Eurydice. The piano plays the sublime song of Orpheus, while the orchestra plays the role of the raging Furies. Finally, the Furies are subdued by this plaintive sad thing, which overcomes everything. I doubt there is really any programmatic intention in Beethoven’s mind. I don’t pay attention to that. I am too busy being the music itself and concerning myself with the problems of execution. This movement is beyond any explanation. I don’t develop an artistic concept when I play it, I only try to give life to the music! This movement is so special that I think I don’t want to say anything about it. I had the privilege all my life of having played it and I hope to continue to play it and have those moments.”

”About the cadenza of the first movement, something funny happened to me in Lyon when I played this concerto with Paul Paray in 1950. A critic wrote that I was a typical American pianist, with steel fingers and a way of playing the piano like a typewriter, without any musical sensitivity. And he added: ‘But where did he find this incredible cadenza? There are limits to bad taste!’ I had of course played Beethoven’s original cadenza. This review, which I have kept, gave all my friends lots to laugh about.”

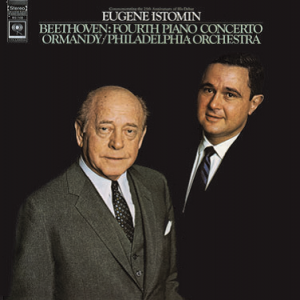

In 1968, Eugene Istomin celebrated the 25th anniversary of his debut. He had chosen Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto for the main events of this celebration. He was to perform it with many orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic under Bernstein and the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Mehta. A recording was scheduled at Carnegie Hall with the Casals Festival Orchestra under Casals. Unfortunately, Casals was so exhausted after the Festival that he had to cancel. Columbia would eventually reschedule the recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy on December 15, 1968. Istomin had performed this concerto with them so many times since 1953 that a single session was enough. The recording went quickly and well, and was released five weeks later. Nevertheless, not having recorded this concerto under Casals would forever be one of Istomin’s greatest regrets.

In 1968, Eugene Istomin celebrated the 25th anniversary of his debut. He had chosen Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto for the main events of this celebration. He was to perform it with many orchestras, including the New York Philharmonic under Bernstein and the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Mehta. A recording was scheduled at Carnegie Hall with the Casals Festival Orchestra under Casals. Unfortunately, Casals was so exhausted after the Festival that he had to cancel. Columbia would eventually reschedule the recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy on December 15, 1968. Istomin had performed this concerto with them so many times since 1953 that a single session was enough. The recording went quickly and well, and was released five weeks later. Nevertheless, not having recorded this concerto under Casals would forever be one of Istomin’s greatest regrets.

In addition to the 1968 official recording, there are about twenty live recordings of this concerto, from 1944 to 1991.

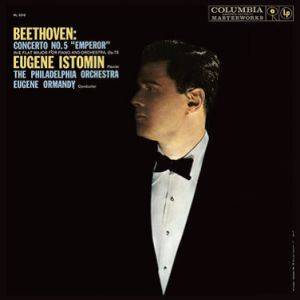

The Fifth Concerto “Emperor”

Istomin performed the Emperor Concerto for the first time in October 1946 at Carnegie Hall with the New York Philharmonic under the direction of Arthur Rodzinski. He was met with a tremendous reception from the audience and a very positive review from the New York Times which pointed out his progress: “a growth both of intellectual perception and technical pianism”. Istomin continued to play this concerto on a regular basis until the very end of his career.

Columbia had arranged to give Serkin priority in the German repertoire, especially for Beethoven and Brahms. However, Istomin’s great success with his performances of the Emperor, especially in 1957 with the New York Philharmonic under Mitropoulos, convinced David Oppenheim that it was worth asking him to record it too.

Unfortunately, in March 1958, when most of the other companies were already systematically recording in stereo, Columbia was just getting started with this new technology. The LP, made with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Ormandy, met with great critical acclaim. Only the mono version could be released, as the stereo sound was not technically acceptable. The result was that the LP did not remain available very long and was never reissued.

Unfortunately, in March 1958, when most of the other companies were already systematically recording in stereo, Columbia was just getting started with this new technology. The LP, made with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Ormandy, met with great critical acclaim. Only the mono version could be released, as the stereo sound was not technically acceptable. The result was that the LP did not remain available very long and was never reissued.

Columbia had suggested that Istomin re-record the Emperor Concerto in stereo in 1961, but the replacement of David Oppenheim by Schuyler Chapin at the head of the Artists and Repertoire department ended in conflict, and all of Istomin’s recordings were cancelled. A concert that Istomin gave in Warsaw with the Polish National Philharmonic under his friend Jerzy Semkow was issued on LP in 1976 on the label Muza. There are also about ten live performances which have been recorded, including some outstanding ones with Mitropoulos in 1957, Munch in 1958, and Ormandy in 1983.

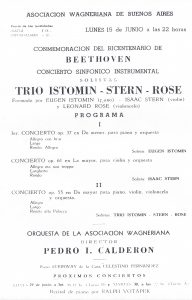

The Triple Concerto

“The first time Isaac Stern, Leonard Rose and I played this concerto was at Carnegie Hall in 1962, under the direction of Alfred Wallenstein. The career of our trio had just begun the previous year in Israel and London. We subsequently played it at least fifty times, very often in marathon concerts with three successive concertos. We ended with the Triple, after Rose and Stern had played the Brahms Double and I had performed a concerto by Beethoven, Mozart or Chopin. The last time we played it was also at Carnegie Hall, with Slava Rostropovitch, in 1977. It is a really difficult work, for the cello in the first place because the high register is very much in demand. It must be said that it is a strange score, rather scrappy, which is also rather uncomfortable for the piano and the violin. Musically, it is not very easy to make it cohesive, both between the soloists and between the soloists and the orchestra. In 1966, we performed it in Cleveland under George Szell. At the first rehearsal, after our successive entries, Szell stopped and asked us with his dry humor: ‘Gentlemen, which of your three tempos should I follow?’ Beyond these difficulties, it is a concerto which always goes over well with the audience, because there are magnificent themes, and very spectacular moments, especially the very virtuoso coda of the last movement!”

Besides the official recording with Ormandy, there are at least three live recordings, including the concert under Szell in Cleveland (1966), which was issued by Doremi and the concert under Casals at Puerto Rico in 1970, which was also filmed.

The Third Concerto

Istomin added Beethoven’s Third Concerto to his repertoire almost twenty years after the Fourth and the Fifth. He broke it in during the summer festivals of 1965, with Ozawa in Ravinia and Leinsdorf in Tanglewood. He continued to perform it regularly, but never as frequently as the two others. The critics soon realized the originality of his interpretation. After a concert with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Ormandy, in February 1966, Irving Lowens remarked: “He chose to concentrate on the lyrically expressive aspects of the concerto rather than on its strong masculinity – a perfectly valid and in many ways convincing interpretation. What was lacking in excitement was compensated for by poetry. There was a degree of elegance in Istomin’s playing that was really uncommon.” Even Harold Schonberg, generally so negative and condescending towards Istomin, wrote after a concert at Carnegie hall in September 1968 that it was a “romantic performance with a point of view, and that is better than the conformity with which so many pianists approach this piece.” Istomin had indeed chosen not to oppose the two themes of the first movement, the first being very energetic and the second more cantabile, as nearly all pianists were used to doing, but instead played them in a kind of poetic continuity.

There is no official recording of the concerto by Istomin, only an unreleased recording made in 2000 in Budapest under Jean-Bernard Pommier, and a few live recordings, including a very beautiful one with Mehta in 1980.

The solo piano works

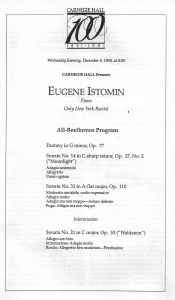

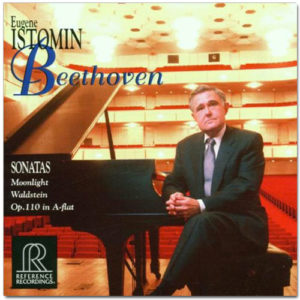

At the turn of the 1990s, Istomin was playing an all-Beethoven program everywhere: the Fantasy in G minor Op. 77, Moonlight Sonata Op. 27 No. 2, Sonata Op. 110, and the Waldstein Sonata. He presented it in these terms.

“Beethoven was fond of his Fantasy in G minor and played it often, but strangely enough, it remains unloved. Some say that it’s ‘bad’ Beethoven, but I don’t think so. In it, we find a lot of his own personality – his fierce temperament, and his great sense of humor, which was not always very refined. It’s like a joke built on scales! First of all, there is a kind of long phrase that is constantly interrupted by scales going up and down. There are collages of ideas and then, in the middle, the arrival of a theme very close to the principal theme of the slow movement of the Emperor Concerto (which dates from the same period), followed by seven variations. At the end, the scales come back. They go down and up again, and finally meet each other – and this ends the work humorously and in a good mood. It’s unique! This fantasy may look clumsy, but it is very endearing. I start the program with it because it unleashes the adrenaline. It’s a kind of catharsis of energy. Then you feel calmer and you can play more introverted music. I like to create a very strong contrast after this Fantasy, by playing immediately afterwards Beethoven’s most atmospheric work, the Moonlight Sonata.

The Sonata Opus 110 further confirms the positive spirit of this great genius who has gone through suffering and resignation. In the first movement there is a tenderness and an affectionate sweetness which is almost unique in all his work. Then there is the drama, the infinitely painful voice of the slow movement and, finally, the rebirth – the phoenix reborn from the ashes and the spirit which eventually triumphs, perhaps even after death. As in all of Beethoven’s late works, the intellectual and mathematical construction plays a prominent role. The subject of the fugue is exactly the same as the theme of the first movement, and the same intervals can be found in the inverted subject of the second fugue which ends the sonata. This unity, this immense arch of construction is so amazing, so incredible. The slow movement, which precedes the first fugue, reminds me of some passages from the St Matthew Passion, or of one of the most poignant works by Mozart, the third movement of the Quintet in G minor K. 516, with the same downward course of the minor scale.

I have played the Sonata No. 21, the ‘Waldstein’ since my very first recital in New York in 1944. Ever since then, I have played it hundreds of times. I hope I have improved. It can touch everyone and has a direct impact on the public. It is one of Beethoven’s greatest achievements. It is a very positive work, which stands for, as he often does, the triumph of the mind and of human will. It is probably one of his works which most impetuously affirms this conviction. That is why it is in C major. There are so many repeated notes, just like an obsession, exactly as in the Fifth Symphony. He is stating to us his absolute conviction that reason, goodwill, and generosity are genuine qualities of humanity, and that they help to overcome adversity. He affirms his faith that the oppressed will triumph and free themselves, like in Fidelio. We are induced to believe in the victory of the human spirit, even if history and the present time constantly prove that this is not true.”

“I had listened to Serkin playing the Sonata No. 24 in F sharp major Opus 78 in a recital and I worked on it with him. I put it sometimes in my programs, but I soon felt that this sonata was too intimate to be performed in big halls. It seems as though Beethoven composed this only for himself and his dedicatee, Therese von Brunswick. There is such tenderness in the first movement! I like to quote Hans von Bülow about its first bars: ‘Beethoven would be immortal even if he had written only these four bars’. As for the final, it is certainly short, but it is monstrously difficult!”

“I had listened to Serkin playing the Sonata No. 24 in F sharp major Opus 78 in a recital and I worked on it with him. I put it sometimes in my programs, but I soon felt that this sonata was too intimate to be performed in big halls. It seems as though Beethoven composed this only for himself and his dedicatee, Therese von Brunswick. There is such tenderness in the first movement! I like to quote Hans von Bülow about its first bars: ‘Beethoven would be immortal even if he had written only these four bars’. As for the final, it is certainly short, but it is monstrously difficult!”

In 1959 and 1960, Istomin recorded two complete sonatas for Columbia (No. 21 and No. 24) and the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata. These recordings were released only in 2015 by Sony. In 1991, when he was currently playing his all-Beethoven recitals, he recorded the Sonatas 14, 21 and 31, which were published by Reference Recordings in 1996.

Chamber Music

Beethoven’s chamber music was an essential part of Istomin’s repertoire at all stages of his career. It constitutes more than a third of his discography.

The first attempts date back to his years at the Curtis Institute, with a few other students like the violinist Nathan Goldstein. He had had the great privilege of spending two whole summers on holiday with the Busch family, in 1944 in Kiawatin and in 1945 in Brattleboro. It was there that he discovered and played all the Beethoven and Brahms violin sonatas with Adolf Busch, and the trios when Hermann Busch joined them. It was a wonderful experience!

The next adventure happened to be the complete Beethoven Violin Sonatas which, at the initiative of Mrs. Leventritt, Istomin performed with Alexander Schneider in the fall of 1949. The first rehearsals were quite stormy. Istomin was so steeped in the great Germanic tradition of Busch that he found Schneider’s playing too schmaltzy, lacking both the rigor and the tension which Busch brought to them. Istomin and Schneider eventually got along quite well and the three series of concerts, in New York, Chicago and Harvard University, were successful. Schneider was satisfied enough to invite Istomin to take part in the first Prades Festival in 1950. The next year, Istomin and Schneider joined Casals to perform and record five Beethoven Trios in Perpignan.

In Prades, Istomin often played the Beethoven Cello Sonatas and Trios with Casals, either privately (especially in 1950 when he spent the full summer there) or in concert. In 1954, Istomin was the artistic director of the Festival, which was entirely dedicated to the chamber music works of Beethoven. They performed together four trios, the Variations WoO 46 and two sonatas (including a fantastic Sonata Op. 5 No. 2 which was recorded by the French Radio and issued on a pirate CD). In 1958, they joined in Puerto Rico for a very moving Sonata Op. 69. Their last Beethoven performance together was in 1965 at Prades Festival (Handel Variations and Sonata Op. 5 No. 1).

Beethoven was also at the heart of the Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio’s history. It culminated in the unprecedented challenge to perform the complete chamber music with piano, in four series of eight concerts (in Switzerland, Paris, London and New York). This was one of the most highlighted events during the Beethoven Bicentennial year celebrations. The recording of the complete works of Beethoven for piano trio, released by Columbia in early 1971, won numerous prizes, including a Grammy Award.

The recording of the complete violin and cello sonatas was also planned. Four sonatas had been recorded in 1969 but Istomin, in serious conflict with Columbia, decided to interrupt it. Out of friendship for Stern, he completed the recording of the Violin Sonatas in 1982 and 1983, without even signing a contract with Columbia. After the Trio was disbanded, Istomin rarely played Beethoven’s chamber music, except in Evian, where there was a fabulous Archduke Trio in 1990, with Stern and Rostropovich.

The Beethoven works which ultimately Istomin never played.

Istomin had always thought he would play all the Beethoven concertos, waiting for the right occasion to tackle the first two. The Second was a specialty of two of his closest friends, Fleisher and Kapell. He felt it would be unfair to challenge them in this rarely programmed concerto. Nevertheless, in October 1954, the Cleveland Orchestra announced that Istomin would perform it. Perhaps because he did not feel ready, the program was changed, and he played the Fourth.

In the late 60s, Istomin hoped to be entrusted by Columbia to record the complete Concertos for the Beethoven Year. The project was under discussion but was eventually abandoned. Columbia decided to promote Serkin’s recordings, despite their age and the fact that they had been made with two different conductors and orchestras. In the mid-90s, there was also Vozlinsky’s idea that Istomin perform the complete series with the Orchestre de Paris conducted by Sawallisch. However, Vozlinsky eventually hired Radu Lupu.

The small number of piano sonatas performed by Istomin is even more surprising. There were at least two reasons for this. First, his extremely busy concert schedule and many diverse interests (in politics, art, literature and even baseball) left him little time to prepare new works. Secondly, his demand for truth, sincerity and perfection was even higher for Beethoven than for any other composer! During his studies at the Curtis, Serkin contributed a great deal towards making him aware of the immense responsibility of performing Beethoven. Serkin’s comments were sometimes traumatic, to such an extent that Istomin renounced playing certain sonatas he had studied with him (like the Pathétique and Op. 54). Serkin’s silences could be even more daunting. In the spring of 1940, Istomin played the Appassionata at a Curtis student recital. Bernstein was overwhelmed with enthusiasm, but Serkin did not say a single word. Istomin clearly understood, perhaps mistakenly, that he had not been up to the task! He would never again play it in concert. Nevertheless, he did give master classes on it and his playing of some passages was proof that the score was still in his heart and fingers.

Notes

All quotations of Istomin are from interviews with Bernard Meillat (in 1987, about the concertos, and 1991, about the solo piano works).

Music

Here are some rare live recordings of two famous Beethoven works (the Waldstein Sonata and the Fourth Concerto) which were at the core of Istomin’s repertoire throughout his career, followed by two much lesser-known works (the Piano Quartet Op. 16 bis and the Fantasy Op. 77).

Beethoven, Sonata No. 21 in C major, Op. 53 “Waldstein”. Eugene Istomin. Live recording at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on October 30, 1991.

.

Beethoven. Concerto No. 4 in G major Op. 58, first movement. Eugene Istomin, Warsaw National Philharmonic. Paul Kletzki. Recorded live in Montreux on September 10, 1963 (the two last movements of this outstanding performance are available in the article dedicated to Paul Kletzki).

.

Beethoven, Piano Quartet in E flat major Op. 16 bis. Eugene Istomin and members of the Budapest Quartet (Joseph Roisman, violin; Boris Kroyt, viola; Mischa Schneider, cello). Live recording at the Library of Congress on November 7, 1958.

.

Beethoven. Fantasy in G minor Op. 77. Eugene Istomin. Recital at Montreux Festival, September 29, 1989.