Eugene Istomin is regarded as a great interpreter of Brahms, at least as much as of Beethoven. He played almost every chamber music work of Brahms, but performed only one of his two concertos and a few solo pieces.

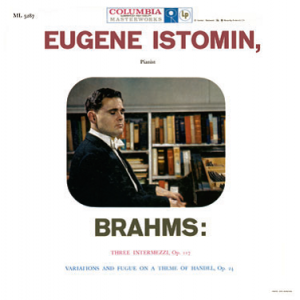

He did not particularly care for the three early Piano Sonatas, considering that they were more a product of perspiration rather than inspiration. He enjoyed playing the Ballades and the last piano pieces (Opus 116 to 119), but he did not consider them to be suitable for the concert hall, but instead, intimate works which should be played only for oneself. He used to quote Brahms: “They are the lullabies of my suffering”; “Even only one listener is too many”! In March 1957, he agreed to record the complete Intermezzi Opus 117 according to David Oppenheim’s suggestion. His recording of the Handel Variations had originally been issued in 1951 on a 10 inch LP, a format which was no longer fashionable. This filler was made in order to allow a reissuing of both works on a 12 inch LP. In the early seventies, Istomin included a Ballade and a few Klavierstücke in his recitals, but he soon abandoned performing them.

He did not particularly care for the three early Piano Sonatas, considering that they were more a product of perspiration rather than inspiration. He enjoyed playing the Ballades and the last piano pieces (Opus 116 to 119), but he did not consider them to be suitable for the concert hall, but instead, intimate works which should be played only for oneself. He used to quote Brahms: “They are the lullabies of my suffering”; “Even only one listener is too many”! In March 1957, he agreed to record the complete Intermezzi Opus 117 according to David Oppenheim’s suggestion. His recording of the Handel Variations had originally been issued in 1951 on a 10 inch LP, a format which was no longer fashionable. This filler was made in order to allow a reissuing of both works on a 12 inch LP. In the early seventies, Istomin included a Ballade and a few Klavierstücke in his recitals, but he soon abandoned performing them.

Handel Variations Opus 24

Istomin heard the Handel Variations for the first time when Rudolf Serkin played them at Carnegie Hall in 1938, when he had just begun his studies with him at the Curtis Institute, and felt an instant affinity for the piece. Istomin performed it many times in the late forties and early fifties with such great success that Columbia proposed that he record it. A few years later Bruno Walter was so impressed by listening to this performance that he agreed to make a recording of the Schumann Concerto, whereas in the past he had always refused to record piano concertos (the only exception was the Emperor Concerto with Gieseking in 1934 and Serkin in 1941). Istomin took up the Handel Variations again in the seventies and recorded them for French Television in 1974.

Istomin heard the Handel Variations for the first time when Rudolf Serkin played them at Carnegie Hall in 1938, when he had just begun his studies with him at the Curtis Institute, and felt an instant affinity for the piece. Istomin performed it many times in the late forties and early fifties with such great success that Columbia proposed that he record it. A few years later Bruno Walter was so impressed by listening to this performance that he agreed to make a recording of the Schumann Concerto, whereas in the past he had always refused to record piano concertos (the only exception was the Emperor Concerto with Gieseking in 1934 and Serkin in 1941). Istomin took up the Handel Variations again in the seventies and recorded them for French Television in 1974.

Piano Concerto No. 1

It is strange that Istomin never performed it. He thought of playing it at various times, all the more so as Ormandy had urged him to perform it, but he never took the final step. It is possible that the shadow of Serkin still loomed over this work, since the first contact had been quite traumatic. Istomin told Stephen Lehmann and Marion Faber, Serkin’s biographers: “I’d been to the Philharmonic to hear him play the Brahms First Piano Concerto with Barbirolli and basking in the pride of now being his pupil decided to learn it for myself. When I came to him for the first lesson with the opening movement more or less “ready”, there were a lot of mislearned notes. He picked up a chair and held it up as if to smash it over my head, because he was so outraged with some of the things that I did. He shouted: ‘Aren’t you ashamed of yourself for treating such a masterpiece this way?’!”

Fifty years later, Istomin still wondered whether the trauma of this reprimand (he was only 14 years at that time) had created the feeling that he could never meet the requirements of this concerto – but he also mentioned other reasons for not playing it. In addition to Serkin, some of Istomin’s closest friends were its outstanding champions: Kapell, Fleisher and Graffman. Moreover, Istomin was convinced that he had much more to communicate in the Second Concerto.

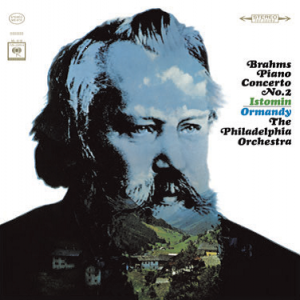

Piano Concerto No. 2

“When I won the Leventritt Competition in 1943, the prize consisted of a concert with the New York Philharmonic, at Carnegie Hall. Arthur Rodzinski, who was its musical director at that time, asked me which concerto I would like to play. I answered: the Brahms Second. For Rodzinski, as well as for all musicians of that epoch, this concerto was one which they considered should only be approached as a mature artist, and I was not yet 18! He didn’t turn me down, but suggested instead that I come and play it during a rehearsal. He sat in an empty Carnegie Hall, leaving the orchestra in the care of his assistant, who was none other than Leonard Bernstein. He was convinced by my playing, so on Sunday the 21st of November 1943, I made my debut with the New York Philharmonic under Arthur Rodzinski in the Brahms Second Concerto. The concert was broadcast by CBS from coast to coast – 8 million listeners. In a few minutes every person interested in classical music knew my name. I had terrible stage fright, which got even worse when I sat down at the piano and realized that it was not the one I had chosen. At the end, I was aware that I hadn’t played very well, even if, paradoxically, hearing the cello solo misplayed in the Andante had given me back some confidence. Serkin was very severe and Bernstein told me: ‘Eugene! What a shame you didn’t play it the way we knew you could!’

“When I won the Leventritt Competition in 1943, the prize consisted of a concert with the New York Philharmonic, at Carnegie Hall. Arthur Rodzinski, who was its musical director at that time, asked me which concerto I would like to play. I answered: the Brahms Second. For Rodzinski, as well as for all musicians of that epoch, this concerto was one which they considered should only be approached as a mature artist, and I was not yet 18! He didn’t turn me down, but suggested instead that I come and play it during a rehearsal. He sat in an empty Carnegie Hall, leaving the orchestra in the care of his assistant, who was none other than Leonard Bernstein. He was convinced by my playing, so on Sunday the 21st of November 1943, I made my debut with the New York Philharmonic under Arthur Rodzinski in the Brahms Second Concerto. The concert was broadcast by CBS from coast to coast – 8 million listeners. In a few minutes every person interested in classical music knew my name. I had terrible stage fright, which got even worse when I sat down at the piano and realized that it was not the one I had chosen. At the end, I was aware that I hadn’t played very well, even if, paradoxically, hearing the cello solo misplayed in the Andante had given me back some confidence. Serkin was very severe and Bernstein told me: ‘Eugene! What a shame you didn’t play it the way we knew you could!’

Nevertheless, my performance was very well received by the public and the critics. What went straight to my heart were the congratulations and encouragement I received from Adolf Busch, who was to engage me for two great tours with his chamber orchestra, and from Bronislaw Huberman. Huberman had played the Brahms Violin Concerto when he was 13, and Brahms was so moved that he dedicated a photo to the young violinist with this inscription: ‘In fond memory from your overjoyed and thankful listener’. Huberman told me in turn: ‘Young man, I played the Brahms Violin Concerto for Brahms himself, and I can assure you that tonight he would have been very happy!”

Istomin continued to perform the Brahms Second Concerto for 45 years, abandoning it for a few years in the seventies, and playing it again often in the eighties, the last time with his friend Mstislav Rostropovitch in 1988. “This concerto never ceased to fascinate me. Among all the piano concertos, it is the one which is the most demanding of the pianist and the musician, and which requires the largest spectrum of emotions and of technical abilities. And it is the concerto which gives the most satisfaction… when you can attain your own expectations!”

Interview with Bernard Meillat, 1987

Chamber Music

For Istomin, a large part of Brahms’ masterpieces are found in his works of so-called “chamber music”. But he underlined that the expression “chamber music” did not make sense, as no musician played it in a salon anymore, and that “ensemble concert music” would be a much more accurate term. He pointed out that these works by Brahms have the same form, the same quality of inspiration and the same ambition as the symphonies. In Brahms’ time, his trios were much more popular than his solo piano works! Of course, this observation about “chamber music” applies equally to Mozart, Beethoven, and all the great composers!

Istomin performed the complete Brahms concert ensemble music, with the exception of the Horn Trio Op. 40 and Piano Quartet Op. 60. This means seven sonatas (with violin, cello, viola or clarinet), four trios, two piano quartets, and the Piano Quintet. He also accompanied Brahms songs on several occasions, the most memorable of them being in 1975 in Puerto Rico where he performed the Lieder Op. 91 with Maureen Forrester and Zukerman. His best-loved works were the Violin Sonata No. 1, the Cello Sonata No. 1 and the Trio Op. 8.

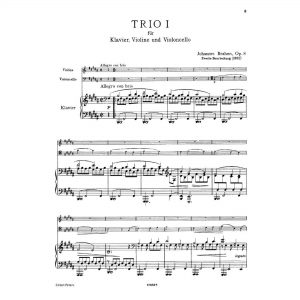

The Trio in B Major, Opus 8

In 1987, John Tibbetts held a very interesting interview with Istomin in which he asked him about this Trio. Istomin was able to give free rein to his love for Brahms in general, and for this work in particular. Tibbetts first asked him what he thought of the revision made in 1888, 34 years after the first version. Brahms trimmed the melodic material, simplified the oversized structure and reduced the duration by one third. Istomin fully approved of this revision, even saying that it could have been reduced even more! But he claims that, as it is, it was one of the towering masterpieces of the 19th century.

“The con brio indication of the first movement is surprising, because the atmosphere is rather majestic. It should not be forgotten that Brahms’ indications do not have the same meaning as they do for other composers. For example, he indicates Vivace for the first movement of his Violin Sonata in G, although it is music of such nobility and serenity! In this case, Vivace actually means, ‘in happiness and bliss’. Certainly, there is brio in the first movement of the Trio Opus 8, and even a lot of it, but it only appears in the development. Then there is a truly irresistible burst of romantic passion. It’s incredibly captivating music. It has the privilege of great works -they totally involve us and we cannot resist letting ourselves be carried away!”

“Brahms didn’t change anything in the Scherzo – he left it as it was, and he was right to do this. It’s a somewhat demonic or, more accurately, ghostly scherzo. The trio makes a striking contrast, with its broad and noble song which is like his body and head, like his entire person. His music sounds just like him!’

“The third movement is one of the peaks of all music, an Everest. It is some of the noblest and most serene music which one can imagine. It is also a less problematic movement! Each musician can feel free to pursue his heights of ecstasy and his quest for the sublime. Good musicians don’t have problems getting along in this movement. We can all sing away, and play away. Of course, we give the foreground to the instrument which is entrusted with the melody! You adjust yourself, and when you “accompany”, you make sure to highlight the harmonies in a way which encourages your partner to sing more intensely, which contributes towards moving the listeners even more. In this movement, there is a perfect balance which allows each instrument to express itself. For the violinist and the cellist, there are very tricky and exciting solos, technically and musically. But, of course, the piano has at least half of the music – we shouldn’t forget that the piano has twice as much to play. The piano is Brahms!”

“The third movement is one of the peaks of all music, an Everest. It is some of the noblest and most serene music which one can imagine. It is also a less problematic movement! Each musician can feel free to pursue his heights of ecstasy and his quest for the sublime. Good musicians don’t have problems getting along in this movement. We can all sing away, and play away. Of course, we give the foreground to the instrument which is entrusted with the melody! You adjust yourself, and when you “accompany”, you make sure to highlight the harmonies in a way which encourages your partner to sing more intensely, which contributes towards moving the listeners even more. In this movement, there is a perfect balance which allows each instrument to express itself. For the violinist and the cellist, there are very tricky and exciting solos, technically and musically. But, of course, the piano has at least half of the music – we shouldn’t forget that the piano has twice as much to play. The piano is Brahms!”

“The fourth movement is a kind of macabre dance in 3/4 in B minor, full of both grace and a ghostly atmosphere. It begins in the pale and cold light of G major. Then it explodes with apocalyptic, cataclysmic violence, with the piano running wild. The middle section provides a respite, with a theme that is both majestic and passionate, but it’s easy to understand that drama is inevitable. It’s not like in Beethoven, where goodness and willpower eventually triumph. The story ends badly, and the hero ends up at the bottom of the river or ravine. It’s really something very special to experience for a performer!”

“The first time I heard this Trio was the recording by Rubinstein, Heifetz and Feuermann when I was very young. Obviously, it’s much too fast, but it’s still beautiful because they’re great artists. I played this Trio many times with Stern and Rose. The last time was in 1982 for a concert in tribute to Abe Fortas, the former Supreme Court judge, who was a dear friend and who had died a few weeks earlier. I also have very special memories with Casals. With him, the cello solo of the third movement was something incredible, an indescribable emotion. The singing of his cello remains forever engraved on my heart. Stern also played it with Casals, and actually Casals was always a presence in our Trio when we played this work, when we played any work.”

“When I played Brahms with Casals in the early years, I bickered with him a little about the tempos, which I often wanted to take faster. Later, I realized that he was right. Brahms’ music needs to take its time in order to live – you don’t gain anything by rushing when it’s not necessary. Last summer, in Marlboro, I was very happy to pass on this experience to talented young musicians by playing this Trio together with them.”

Documents

Brahms. Concerto No. 2 in B flat major Op. 83, first movement (Allegro ma non troppo). Eugene Istomin, Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy. Recorded by Columbia in February 1965.

.

Brahms. Variations on a Theme by Handel Op. 24. Eugene Istomin. Studio recording in 1974.

.

Brahms. Piano Quartet No. 2 in A major Op. 26, the first two movements. Eugene Istomin, piano. Members of the Budapest Quartet (Joseph Roisman, violin; Boris Kroyt, viola; Mischa Schneider, cello. Live recording at the Library of Congress on November 7, 1958.

.

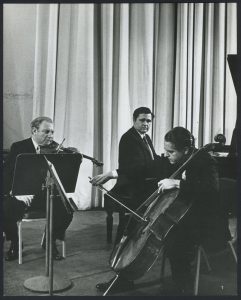

Brahms. Trio No. 2 in C major Op. 87. Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern, Leonard Rose. Filmed by the French Television in 1974.