“Rachmaninoff was made of steel and gold : steel in his arms, gold in his heart. I can never think of this majestic being without tears in my eyes, for I not only admired him as a supreme artist, but I loved him as a man”. This is what Josef Hofmann wrote two years after the composer’s death.

“Rachmaninoff was made of steel and gold : steel in his arms, gold in his heart. I can never think of this majestic being without tears in my eyes, for I not only admired him as a supreme artist, but I loved him as a man”. This is what Josef Hofmann wrote two years after the composer’s death.

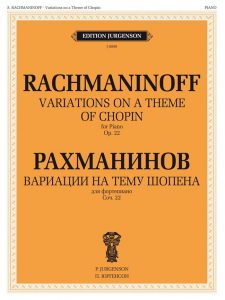

Istomin shared this admiration and affection to the highest degree. For him, Rachmaninoff was always an exemplary model, and an inaccessible ideal. He was the pianist and composer whom Istomin felt he understood most deeply, the one whose case he pleaded with the most eloquence. And yet he did not play his works that often, prematurely abandoning the Third and Fourth Concertos after a few successful performances, or giving up in extremis his plans to perform the Chopin Variations in public, which he had been preparing for three years. There were undoubtedly objective reasons- but the main one, largely subjective, was that for him Rachmaninoff was a symbol of absolute perfection – and he was very anxious to be up to the challenge. The fear of having to deal with a mediocre piano that would make the task even more difficult, or of being accompanied by an unprepared orchestra or a mediocre conductor – was so great that he ultimately renounced playing these works.

The many interviews in which Istomin spoke about Rachmaninoff (with John Tibbets, Robert Jacobson, David Dubal, James Gollin, Birgitta Dahlin, Antoine Livio, Bernard Meillat) complement each other and form a rich collection of memories and reflections. It is presented below.

Rachmaninoff the pianist

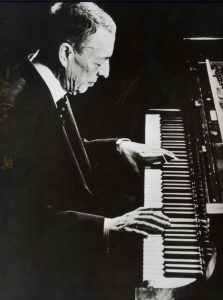

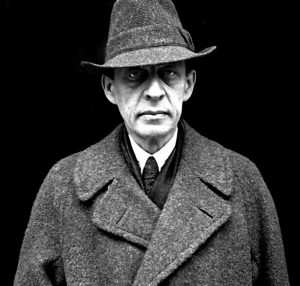

“Rachmaninoff is undoubtedly the greatest pianist I have ever heard. He had an irresistible, compelling eloquence, which came from his sound and the depth of feeling he conveyed. His face looked like a Buddhist mask, but what came out of the piano was both intoxicating and upsetting. I kept alive in me the memory of his playing, his presence on the stage, this incredible combination of power and speed, like a tiger. What came out of the piano was gold, and made your heart melt.”

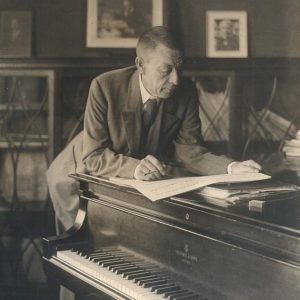

“He did not move at all at the keyboard. He was so big, so large that the keyboard looked like a chessboard. He could jump from one end to the other. For example, there is the cadenza of the first movement of the Third Concerto with its huge leaps, and also one particular variation of the Chopin Variations, a great work rarely played, jumping back and forth. I remember his playing, how he looked when he did that, he was still absolutely impassive, like Jascha Heifetz. The fire and the terrific passion came out of the sound and not from his face! It was all happening under the surface. Nowadays the players visualize how they feel, Rachmaninoff would be horrified.”

“His fingers were like quicksilver, with such rapidity, expressiveness and incisiveness! He had a great sense of dynamics, with small accents, little electric shocks. It was rather light playing, without crashing chords. He had enormous hands, but his finger work was very light and accented. There was a kind of impetus, and a sense of building up and drive. The tone was of such a gorgeous beauty, with such a subtlety of phrasing. It was more than incredible virtuosity. There was an overpowering eloquence that came from his tone and the depth of feeling he projected. And you know, he played very fast, terribly fast at times – sometimes too fast!”

“His fingers were like quicksilver, with such rapidity, expressiveness and incisiveness! He had a great sense of dynamics, with small accents, little electric shocks. It was rather light playing, without crashing chords. He had enormous hands, but his finger work was very light and accented. There was a kind of impetus, and a sense of building up and drive. The tone was of such a gorgeous beauty, with such a subtlety of phrasing. It was more than incredible virtuosity. There was an overpowering eloquence that came from his tone and the depth of feeling he projected. And you know, he played very fast, terribly fast at times – sometimes too fast!”

Rachmaninoff in concert

“Subsequently I heard him a dozen times, including his last concert in Philadelphia and in New York in 1942. The very last time, I was sitting onstage at the Philadelphia Academy of Music with my teacher, Rudolf Serkin, the two of us in back of Rachmaninoff. He was to die the next year.

“Subsequently I heard him a dozen times, including his last concert in Philadelphia and in New York in 1942. The very last time, I was sitting onstage at the Philadelphia Academy of Music with my teacher, Rudolf Serkin, the two of us in back of Rachmaninoff. He was to die the next year.

I mainly heard him play his own works, but his performances of other music were always masterful, even of Mozart and Beethoven. I heard him play Mozart’s Sonata K. 331, with the Turkish March, and three Beethoven sonatas: Opus 111, the Tempest, and Opus 90 in E major. They were interpretations of a great composer who has the privilege of dealing with other composers’ works! He could take liberties in Chopin and Schumann that I would not dare take. But I have no right to judge! Rachmaninoff actually played everything as though it were Rachmaninoff.”

Rachmaninoff’s personality

“He had this dark sad expression. He was ill and the situation in the world, the problems in Russia, the war in Europe, all contributed to make him depressed. The way modernism in art and music was developing affected him. I have the feeling that he knew he was being overtaken by events, by developments.

“He had this dark sad expression. He was ill and the situation in the world, the problems in Russia, the war in Europe, all contributed to make him depressed. The way modernism in art and music was developing affected him. I have the feeling that he knew he was being overtaken by events, by developments.

He needed to earn money, so he had to practice and give concerts, even though he would have liked to spend more time composing. He suffered a lot from stage fright. And at the end of his concerts, he knew that people would not let him go until he played the C sharp minor Prelude, which infuriated him. He condescended to play it, but he grew to despise this piece.

His inspiration was giving signs of drying up. His last works, the Fourth Concerto and the Symphonic Dances, two marvelous works, were pilloried, taken very lightly, and treated very badly. I remember Serkin telling me that Rachmaninoff told him that his music was regarded as cheap stuff, cheap trash. He personally did not think so, but he knew that many musicians thought that way. Yes, he was sad, somber, melancholic, and impassible – but I know from his friends and family that he was also extremely tender and gentle, and that he liked to laugh a lot.”

His inspiration was giving signs of drying up. His last works, the Fourth Concerto and the Symphonic Dances, two marvelous works, were pilloried, taken very lightly, and treated very badly. I remember Serkin telling me that Rachmaninoff told him that his music was regarded as cheap stuff, cheap trash. He personally did not think so, but he knew that many musicians thought that way. Yes, he was sad, somber, melancholic, and impassible – but I know from his friends and family that he was also extremely tender and gentle, and that he liked to laugh a lot.”

Anecdote with Horowitz and Cortot

“I remember a rather naughty anecdote Horowitz told me. One day he called Horowitz on the phone, (he used to call him Gorowitz, because Russians pronounce the H like that): ‘Come over immediately, I have something I want you to hear’. Horowitz dropped everything and ran over to Rachmaninoff’s. When he arrived, Rachmaninoff said: “Sit down for a minute!”, and he put on a recording of Alfred Cortot playing some Chopin, a ballade. There were so many wrong notes, so many mistakes! The old boy was slapping his thighs and roaring with laughter, making so much fun of Cortot’s wrong notes, while exclaiming ‘But can you believe it? Can you believe it?’ Beyond the sense of humor, it reveals also Rachmaninoff’s concern for perfection. Today, we don’t even have to play well – we just paste in the correct notes in place of the wrong ones. It is a totally unreal, artificial, fake, phony thing. But in the twenties and thirties, you had to play up to four and a half minutes at a time and you couldn’t do anything about the notes you missed, you could only choose the takes. Rachmaninoff was an incredibly accurate player, as was Jascha Heifetz for example.”

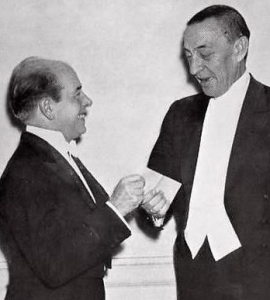

Rachmaninoff and Ormandy

In an interview with John Tibbetts, Istomin related a delightful anecdote that Ormandy had confided to him: “I can’t resist telling you a story about Ormandy playing the Paganini Rhapsody with Rachmaninoff, one of the early times they collaborated when Ormandy was still in Minneapolis. When they got to the fast variation, Rachmaninoff got completely lost. He started racing up and down the keyboard in 16th notes. What Ormandy, the young conductor, told me was, ‘I could see my life going out, the way a drowning man dies. This is the end of me; they’ll run me out of town for getting Rachmaninoff mixed up.’ After the performance Ormandy didn’t know what to do with himself. He stayed in his dressing-room, until he heard a knock on the door. [Imitating Rachmaninoff’s deep bass voice], ‘I’m sorry, Mr. Ormandy’.”

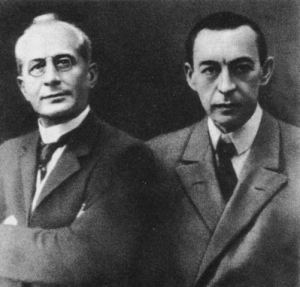

Rachmaninoff and Siloti

“Siloti always considered Rachmaninoff to be one of his protégés, and did not refrain from openly criticizing him. One day, he was seated in a box at one of Rachmaninoff’s concerts at Carnegie Hall with, I believe, his friend Alexander Greiner, who was head of Steinway Concerts and Artists. At one point, while Rachmaninoff was playing a Beethoven sonata, Siloti leaned over to Greiner and whispered in his ear: ‘He knows I’m here. Why didn’t he ask me?’ – meaning that he was playing it all wrong! Naturally, this story made its way back to Rachmaninoff, who complained: ‘And to think that I have to continue giving him free tickets to my concerts!’ It is a funny anecdote, but of course they remained very close until the end.”

Istomin auditioned for Rachmaninoff in 1932 and forgot all about it!

When he was seven, Istomin went to play for Rachmaninoff. Kyriena Siloti had taken him, and he played one of the little Beethoven Sonatas from Op. 49. Rachmaninoff treated him very kindly, kissing him on the forehead and obviously happy with what he had heard. He complimented the young pianist, but then asked Kyriena Siloti: “Are you giving him technique?” He probably thought it was absolutely necessary from that age to be already spending long hours practicing scales and all kinds of exercises.

Strangely enough, Istomin had buried this event deep in his subconscious, probably because he felt so guilty for having left Siloti so suddenly. Forty years later, when Kyriena unexpectedly reminded him about it, all his memories came flooding back – the West End apartment, his face, the way he looked… Aside from this almost unbelievable memory lapse, what amazed Istomin the most was that in retrospect, he felt that he hadn’t been frightened at all: “A few years later, I would have been paralyzed, unable to play a note for this musical giant!”

Performing Rachmaninoff

“For playing Rachmaninoff, you need to sing a lot, to sing Russian, sentimental and passionate, heart-stopping songs, which express feelings about romance, about sadness, about passionate longing. You also need fingers like golden steel, with feather lightness. And you have to be a terrific player! There are quite a lot of terrific players, but there are very few who can touch our guts and heart.”

“There is a pianism specific to Rachmaninoff, a virtuosity strewn with accents which resemble sparks. I can play Beethoven and Mozart any time. For Chopin and Debussy, if I haven’t played them in a long time, I need a few hours. For Rachmaninoff, I need at least a week to re-adapt.”

“Rachmaninoff was a great Romantic, the quintessence of Romanticism. By Romantic I do not mean exaggerated sentimentality or distorting the bar lines, etc. Rachmaninoff didn’t do that, he played very straightforwardly. He tended to play his works much faster than anyone else today, partly because of the excitement, the nervousness from stage fright, and adrenaline, but also because he felt a kind of impulse, the need to mix this excitement with the tunefulness of his music. Today most pianists play his works too slowly and sentimentally.”

The Second Concerto

“I am very proud of my recording of Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto. I even think it is perhaps the best recording of this piece. It’s very immodest to say that, but I mean it. My career began as a Beethoven and Brahms specialist. I was a student of Rudolf Serkin. I made my first tours with Adolf Busch playing Bach and Mozart. I had completely put aside my Russian roots. As a youngster I didn’t want the easy success that the Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff or Prokofiev concertos brought. William Kapell, Gary Graffman and Byron Janis followed this road, but I didn’t – I was much too pretentious and snobbish. I also thought it was easy to play these Russian concertos. In fact, as I was preparing them, I realized that it wasn’t that easy!”

“When I decided to record the Rachmaninoff Second, I asked Vladimir Horowitz to let me use his piano, the famous CD 18 that Steinway reserved exclusively for him. Horowitz was not performing at that time; it was during one of his two phases of hibernation. He was kind enough to accept! I am very proud he lent me his piano, something he had never done for anyone else. Oddly, he had never performed this concerto and wasn’t even thinking of doing so in the future. Maybe he thought that I was the right pianist for making a modern reference recording of this work. Horowitz had used this piano for many recordings, like the Tchaikovsky and the Brahms concertos with Toscanini. It was especially brilliant in the upper range, and had enormous power in the bass notes. It was the ideal instrument for playing Rachmaninoff. The key dip was incredibly shallow, which allows for very quick playing and subtle accenting. The power of the fortissimos and the dynamic range were exceptional. It was a tricky instrument which required absolute control. I fell in love with this piano and ended up buying it many years later.”

“When I decided to record the Rachmaninoff Second, I asked Vladimir Horowitz to let me use his piano, the famous CD 18 that Steinway reserved exclusively for him. Horowitz was not performing at that time; it was during one of his two phases of hibernation. He was kind enough to accept! I am very proud he lent me his piano, something he had never done for anyone else. Oddly, he had never performed this concerto and wasn’t even thinking of doing so in the future. Maybe he thought that I was the right pianist for making a modern reference recording of this work. Horowitz had used this piano for many recordings, like the Tchaikovsky and the Brahms concertos with Toscanini. It was especially brilliant in the upper range, and had enormous power in the bass notes. It was the ideal instrument for playing Rachmaninoff. The key dip was incredibly shallow, which allows for very quick playing and subtle accenting. The power of the fortissimos and the dynamic range were exceptional. It was a tricky instrument which required absolute control. I fell in love with this piano and ended up buying it many years later.”

“I was very moved to make this record with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Ormandy. I had heard Rachmaninoff play his own concertos with them several times when I was studying at the Curtis Institute. He loved the musicians of the Philadelphia Orchestra, to the point of dedicating his Symphonic Dances to them, as well as to Ormandy. It was a great success. Two hundred thousand copies were sold, and my fellow pianists continue to tell me about it. It’s amazing it’s never been reissued. It was made in mono just before the arrival of stereo. I was supposed to do it again in stereo in the spring of 1961 when I was playing it again in Philadelphia with Ormandy, but that was cancelled because I clashed with the management of Columbia.”

“I am often asked about the chords at the beginning of the concerto: ‘How can you break these chords and produce such a sound?’ Rachmaninoff’s hands were so big that he didn’t need to break the chords. He could stretch an octave and a half. I had to break them because my hands are not that big! And to think that Rachmaninoff wrote his Third Concerto for Josef Hofmann, who couldn’t play it since his hands were too small – he could just barely play an octave. There are only a few pianists with huge hands, like Van Cliburn, who don’t have to break the chords in the Second Concerto. In the end, it’s not so important. The main point is the sound of these chords. I could hear them resonating in my head and in my heart, and my hands found the way to achieve it!”

The Third Concerto

Istomin performed Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto for the first and last time, on March 12 and 13, 1944. It was with the Chicago Symphony under its then music director, Désiré Defauw. He was 18 years old and had fallen in love with the concerto. He had even played it for Serkin, who was very impressed. The concerts were very well received. The audience cheered him repeatedly and let him go only after he played a Chopin Nocturne as an encore. And yet, he would never play that concerto again! When asked why, he didn’t really have a clear explanation: “Maybe I had the feeling that I had an excessive success. I didn’t think I had played that well. And then I went on tour with Busch, playing more than forty concerts of Mozart and Bach. That was my ideal, it was to these composers that I had to devote myself.”

The Fourth Concerto

In the early 1980s, Istomin became fond of Rachmaninoff’s Fourth Concerto. He had once heard the composer play it in Philadelphia. The work had been pulled to pieces when it was premiered. Critics spoke of a debacle, a “monument of boredom, length, banality and toc”, one of them daring to write that “Mrs. Cécile Chaminade might safely have perpetrated it on her third glass of vodka”. Two revisions were not enough to improve its reputation. When he came to record it with Rachmaninoff at the piano, Jack Pfeiffer, the artistic director of RCA refused to pay for any rehearsal time and the recording was the first run-through with the orchestra!

In the early 1980s, Istomin became fond of Rachmaninoff’s Fourth Concerto. He had once heard the composer play it in Philadelphia. The work had been pulled to pieces when it was premiered. Critics spoke of a debacle, a “monument of boredom, length, banality and toc”, one of them daring to write that “Mrs. Cécile Chaminade might safely have perpetrated it on her third glass of vodka”. Two revisions were not enough to improve its reputation. When he came to record it with Rachmaninoff at the piano, Jack Pfeiffer, the artistic director of RCA refused to pay for any rehearsal time and the recording was the first run-through with the orchestra!

Istomin recognized that it contained a mix of Rachmaninoff’s Russian soul and American culture. Such an association touched him deeply because, as the son of a Russian émigré, he had experienced and felt the same things. But for many musicians and music lovers, this concerto was an indigestible hodgepodge – music for nightclubs. Istomin agreed but added: “Nightclub music, yes, but sublime!” Istomin did not hold nightclub music in contempt, and even loved Frank Sinatra.

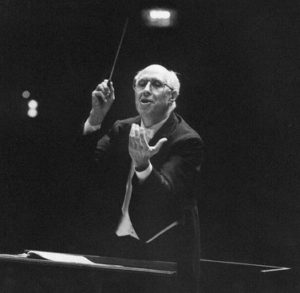

Istomin first performed Rachmaninoff’s Fourth Concerto in September 1983 with the National Symphony under the direction of Mstislav Rostropovich. Who better than Slava could understand this music and be attentive to his soloist and friend? The reception from the audience and critics was very warm. Joseph McLellan reported enthusiastically in the Washington Post: “Rostropovich and the National Symphony and Eugene Istomin gave Rachmaninoff’s Fourth Piano Concerto the performance of a lifetime. Istomin’s solo performance was a revelation… Rostropovich’s interpretation was both thoughtful and powerful – a bit understated at the beginning while he was seeking an ideal balance with the soloist, but quite powerful and assured thereafter. Istomin emphasized the American elements in the music more than any performer I have heard, without disguising its essentially Russian soul, and it was most effective.”

Istomin played it again a few weeks later with the Rochester Philharmonic. It happened to be more difficult because there was not enough time to rehearse. On the first evening, there were a few lapses and hesitations in the orchestra. The next day, thanks to David Zinman’s dedication and expertise, everything worked perfectly.

Istomin would have liked to continue to play and even record this concerto which was so close to his heart. He admired the recording made by Michelangeli in 1957, but thought that his own version would be quite different, and most likely, more idiomatic! However, orchestras and conductors were very reluctant to program an unfamiliar work which required extensive rehearsal and would not attract concert-goers. In the following seasons, there were very few proposals, none of which provided sufficient guarantees about the orchestra level, the conductor or the allotted rehearsal time. Istomin could not bear the idea of giving botched performances of this concerto, and eventually removed it from his repertoire.

Istomin would have liked to continue to play and even record this concerto which was so close to his heart. He admired the recording made by Michelangeli in 1957, but thought that his own version would be quite different, and most likely, more idiomatic! However, orchestras and conductors were very reluctant to program an unfamiliar work which required extensive rehearsal and would not attract concert-goers. In the following seasons, there were very few proposals, none of which provided sufficient guarantees about the orchestra level, the conductor or the allotted rehearsal time. Istomin could not bear the idea of giving botched performances of this concerto, and eventually removed it from his repertoire.

The solo works

Apart from the late 1940s, when he combined Chopin and Rachmaninoff preludes in his recital programs, Istomin did not perform solo piano works by Rachmaninoff. The only exception was Rachmaninoff’s transcription of one of his songs, Daisies, which he occasionally played as an encore. In 1974, Horowitz played Rachmaninoff’s Variations on a Theme by Chopin, telling him: “This is a work for you!” In the autumn of 1977, after two years of preparation, Istomin declared himself to be ready. He began talking about the work to journalists. In an interview for the Swedish Radio, he spoke about his fascination with these Variations: “an absolute masterpiece, of extreme difficulty, the ultimate in piano virtuosity, which is so rarely played because of its extreme difficulty. And you must have a piano which responds perfectly. If not, you can expect to suffer a great deal!” When he proposed the Chopin Variations in his recital program for the following season, most of the organizers asked to make a change and to play genuine Chopin rather than the Rachmaninoff Variations. Rather than performing them only occasionally on temperamental pianos, he preferred to give up.

Apart from the late 1940s, when he combined Chopin and Rachmaninoff preludes in his recital programs, Istomin did not perform solo piano works by Rachmaninoff. The only exception was Rachmaninoff’s transcription of one of his songs, Daisies, which he occasionally played as an encore. In 1974, Horowitz played Rachmaninoff’s Variations on a Theme by Chopin, telling him: “This is a work for you!” In the autumn of 1977, after two years of preparation, Istomin declared himself to be ready. He began talking about the work to journalists. In an interview for the Swedish Radio, he spoke about his fascination with these Variations: “an absolute masterpiece, of extreme difficulty, the ultimate in piano virtuosity, which is so rarely played because of its extreme difficulty. And you must have a piano which responds perfectly. If not, you can expect to suffer a great deal!” When he proposed the Chopin Variations in his recital program for the following season, most of the organizers asked to make a change and to play genuine Chopin rather than the Rachmaninoff Variations. Rather than performing them only occasionally on temperamental pianos, he preferred to give up.

In the late 1980s, before embarking on the adventure of extensive tours, with his own pianos transported in a specially-adapted truck, Istomin decided to radically renew his recital programs. One of the new programs, carefully assembled, ended with four pieces by Rachmaninoff: the Prelude Op. 32 No. 7, the Oriental Sketch, Tchaikovsky’s Lullaby (arrangement of the song Op. 16 No. 1), which is the last work Rachmaninoff worked on, and the Etude-Tableau Op. 39 No. 9. He played this program a hundred times and recorded it on a CD which was published by the French label Adda in 1987.

For his own pleasure, and also as a barometer of his pianistic form, he loved to play Rachmaninoff’s transcription of Bach’s Third Partita for Solo Violin, in particular the Prelude. He played it frequently at home, and on occasion as an encore.

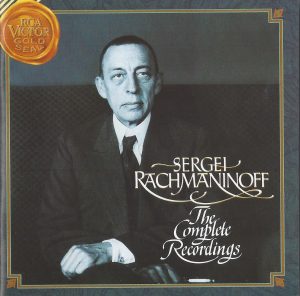

A plea for Rachmaninoff’s recordings

“It is a shame that musicians and music lovers are not more familiar with the recordings Rachmaninoff made of his own music, including as a conductor. Radio stations no longer broadcast them because the sound would be too old. Who wouldn’t be interested in hearing a great composer play his own music? Especially since he plays it better than anyone else! At the very least, it should serve as a model! Every time I played his works, it was him, along with my memories of his concerts and his recordings, which were my model, inspiration, and my ideal.”

“It is a shame that musicians and music lovers are not more familiar with the recordings Rachmaninoff made of his own music, including as a conductor. Radio stations no longer broadcast them because the sound would be too old. Who wouldn’t be interested in hearing a great composer play his own music? Especially since he plays it better than anyone else! At the very least, it should serve as a model! Every time I played his works, it was him, along with my memories of his concerts and his recordings, which were my model, inspiration, and my ideal.”

Music

Rachmaninoff. Concerto No. 2 in C minor Op. 18, third movement. Eugene Istomin, Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy. Recorded for Columbia on April 8, 1956

.

Bach – Rachmaninoff. Prelude from the Partita No. 3 for Solo Violin. Sergei Rachmaninoff, recorded in February 1942. (For his own pleasure, and also as a barometer of his pianistic form, Istomin loved to play this piece, which he occasionally performed as an encore)