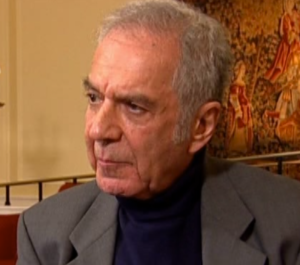

Claude Frank (1925-2014) was one of Istomin’s closest friends for half a century. They met in the fall of 1953, just after the death of Kapell, at Mrs. Leventritt’s, where Frank had come to give lessons to the very promising young pianist Richard Goode. Claude Frank had not really launched his career yet, although he was already 28 years old. The course of his life had been disrupted by the tragic events of history. Born in Nuremberg in 1925, he had to flee Germany because of the Nazis and began his studies in Paris at the Conservatoire in 1937. When France was defeated, he took refuge in Madrid and finally reached the United States in 1941 with part of his family. There he became a pupil of Schnabel, who had already noticed him in Europe. As a naturalized American, he was forced to interrupt his education in 1944 to join the Army. After the War, he also studied composition with Paul Dessau at Columbia University and conducting with Koussevitzky at Tanglewood. In 1947, his first New York recital was well received and followed by an engagement with the NBC Symphony, but his career developed only in the mid-50s after he entered the Leventritt Competition.

Claude Frank (1925-2014) was one of Istomin’s closest friends for half a century. They met in the fall of 1953, just after the death of Kapell, at Mrs. Leventritt’s, where Frank had come to give lessons to the very promising young pianist Richard Goode. Claude Frank had not really launched his career yet, although he was already 28 years old. The course of his life had been disrupted by the tragic events of history. Born in Nuremberg in 1925, he had to flee Germany because of the Nazis and began his studies in Paris at the Conservatoire in 1937. When France was defeated, he took refuge in Madrid and finally reached the United States in 1941 with part of his family. There he became a pupil of Schnabel, who had already noticed him in Europe. As a naturalized American, he was forced to interrupt his education in 1944 to join the Army. After the War, he also studied composition with Paul Dessau at Columbia University and conducting with Koussevitzky at Tanglewood. In 1947, his first New York recital was well received and followed by an engagement with the NBC Symphony, but his career developed only in the mid-50s after he entered the Leventritt Competition.

Istomin, who was on the jury, told the story in his own words: “He should have won, but he didn’t win it because he screwed up some passages in Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto. He was in the finals with John Browning and Van Cliburn. He should have prevailed over them, although both of them were terrific pianists. How could one not be impressed by Van’s flawless perfection in Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody, by his spectacular charisma and his huge hands and charm? The only way to forestall him would have been to be quite close to his technical perfection and to surpass him in terms of pure musicality, which was the ideal of the Leventritt Competition. Claude did not succeed. However, as a result of that, I talked with him and tried to help him, and we became very close.”

Istomin spared no effort towards pushing Claude Frank to reach the heights that his talent predicted. Frank told James Gollin that their relationship had long continued in the same spirit as during the competition: “He was a judge, I was a contestant, and somehow that never completely changed.” But Istomin put their relationship in another perspective: “I was, again, a kind of mentor to him. Not really, because I had a great respect for him. He was a very strong musician, trained by Schnabel in all those values of expressiveness and seeing the whole Gestalt of a work. Anyway, we had a great deal of respect for each other.”

In his memoirs, My Nine Lives, Leon Fleisher expresses his high esteem for Claude Frank (both of them were Schnabel’s students), but also his jealousy: “I admired him enormously. I thought he was a wonderful musician and pianist. But he was also my rival for the thing I wanted most in the world.” The “thing” was Marjorie Weitzner, a very attractive young artist with a passion for music, especially for lieder. Claude Frank and Leon Fleisher fought over her favors for a long time. She made them both languish and finally ended up marrying a Mr. Morris and working for her father, who was a prominent collector and art dealer.

In his memoirs, My Nine Lives, Leon Fleisher expresses his high esteem for Claude Frank (both of them were Schnabel’s students), but also his jealousy: “I admired him enormously. I thought he was a wonderful musician and pianist. But he was also my rival for the thing I wanted most in the world.” The “thing” was Marjorie Weitzner, a very attractive young artist with a passion for music, especially for lieder. Claude Frank and Leon Fleisher fought over her favors for a long time. She made them both languish and finally ended up marrying a Mr. Morris and working for her father, who was a prominent collector and art dealer.

The links between the OYAPS (Outstanding Young American Pianists association!) became less close in the 60s, due to their family obligations and the internationalization of their careers, but Claude Frank remained Istomin’s closest colleague. Their talks were not only about music, but also about many other issues, especially literature and politics. Both were voracious readers and could not fathom why so many musicians did not nurture their intelligence and sensitivity with other arts. Claude Frank shared Istomin’s enthusiasm after his meeting with Kennedy, and he encouraged his plans to convince the American government that culture, and especially music, was a very efficient weapon in diplomatic strategy and the struggle of influence against the Soviet Union.

The links between the OYAPS (Outstanding Young American Pianists association!) became less close in the 60s, due to their family obligations and the internationalization of their careers, but Claude Frank remained Istomin’s closest colleague. Their talks were not only about music, but also about many other issues, especially literature and politics. Both were voracious readers and could not fathom why so many musicians did not nurture their intelligence and sensitivity with other arts. Claude Frank shared Istomin’s enthusiasm after his meeting with Kennedy, and he encouraged his plans to convince the American government that culture, and especially music, was a very efficient weapon in diplomatic strategy and the struggle of influence against the Soviet Union.

Istomin was close to the whole Frank family. In 1959, he was Claude’s best man when he married Lilian Kallir in Marlboro. Claude and Lilian met each other briefly in Lisbon in 1941, when they were leaving for America. They had not exchanged a single word. They would meet again many years later, in Tanglewood, and would be married in Marlboro. In 1975, Claude and Lilian attended Istomin’s wedding with Marta Casals. They were still there in 2000, this time playing duets for Istomin’s 75th birthday celebration. .

Istomin wished that Claude Frank would have been better acknowledged as the immense soloist he was. Performing and recording the complete Beethoven Piano Sonatas in 1970 rendered Frank unanimous praise. One would have thought that his career would gain a new impetus, but the records were soon removed from the catalogue. Istomin considered that Frank had also suffered from his image as a “chamber musician”, being a member of the Boston Chamber Players and a regular partner of the greatest string quartets (Juilliard, Guarneri, Cleveland, Emerson, Tokyo…). Frank did not care that much and mostly wanted to play the music he liked, especially chamber music. He also formed two family ensembles, a piano duo with his wife Lilian Kallir, and a piano-violin duo with his daughter Pamela.

Istomin invited Claude and Pamela to take part in his Great Conversations about Chamber Music and virtuoso string playing at the Library of Congress. When he asked Claude which musicians remained references for him, his answer most likely did not come as a surprise to Istomin: “Casals and Szigeti! Musicians whose message goes beyond the notes…” As for the question of whether chamber music would be a separate field, Claude Frank answered with a quote from Serkin that Istomin would certainly not disown: “Chamber music? I don’t know what it is! I only know music.”

At Istomin’s funeral, Claude Frank spoke out and expressed his deep respect for the musician and his profound affection for the man: “There was no friend like Eugene. He helped many, many of his colleagues with conductors, with engagements, with musical ideas, with personal matters.”

Documents

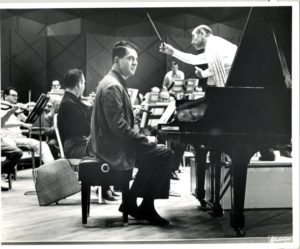

Mozart. Concerto No. 24 in C minor K. 491, first movement (Allegro). Claude Frank. New England Conservatory Orchestra. Leon Fleisher. An exceptional concert in homage to Artur Schnabel on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of his birth, which brought together two of his most eminent disciples. Recorded live on December 15, 1982 and issued on LP by Audiophon.

Audio Player.

Beethoven. Sonata No. 28 in A major op. 101, first movement. Claude Frank. Excerpt from the complete Sonatas published in 1970.

.

.