When Istomin’s parents became aware of their son’s exceptional musical abilities, they felt somewhat helpless. They were not musicians, had no connections in the music world, and had no money. George Istomin decided to appeal to the solidarity of the Russian exiles and requested an audience with Prince Serge Obolenski, who had been his fellow student at the Military Academy and his superior during the War. Obolenski promised to arrange a meeting with the legendary figure of Russian music, Alexander Siloti.

Siloti’s career and exile in the United States

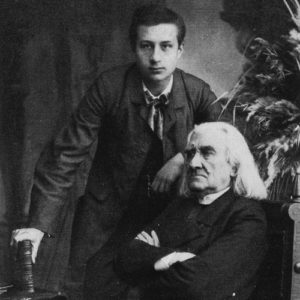

Siloti had been at one time Franz Liszt’s favorite student. He had studied composition with Tchaikovsky and orchestration with Rimsky-Korsakov, and had been the teacher of Sergei Rachmaninoff, who was his cousin. He was also the brother-in-law of the painter Leon Bakst and had married the daughter of Paul Tretyakov, the famous patron and art collector. Born in 1863, he had had a brilliant career as a pianist, spending ten years concertizing throughout Europe and touring the United States in 1898. Siloti later devoted his time to conducting. In 1903, he created the Siloti Concerts in St. Petersburg, thanks to his wife’s considerable fortune. Until 1917, the programming was a permanent festival, attracting the most prestigious soloists and conductors of that time: Ysaÿe, Casals, Chaliapin, Rachmaninoff, Auer, Enesco, Hofmann, Nikisch, Mengelberg, Weingartner… Contemporary music was well-represented with works by Debussy, Elgar, Sibelius, Mahler, Richard Strauss, Rimsky-Korsakov, Prokofiev, and Stravinsky. The Siloti Salon was the favorite meeting place for high society and the artistic avant-garde of musicians, painters, writers and theatre people.

After the Revolution, the Bolsheviks offered Siloti various responsibilities, including the direction of the Mariinsky Theatre, but the rampant instability, violence and misery made him decide to flee the country in 1919. After a disappointing move to England, he decided to go to the United States in 1922. He had given up conducting and resumed his career as pianist, but after a few tours, he played less and less often in public. One of his last concerts was with the New York Philharmonic under Toscanini in November 1930. He was still at the peak of his artistry and performed two works by Liszt (the Danse Macabre and the arrangement of Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy). He gave another recital at Carnegie Hall the next year but from then on, devoted himself mainly to teaching. He accepted a position at the Juilliard School in 1924, and held it until 1942, three years before his death. He also taught private students in his apartment at the Ansonia Hotel where – just as in the old days – he continued to receive all the artists of the Russian diaspora, including Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, Koussevitsky, and the daughter of Leon Tolstoy.

The hospitality of the Siloti family

At Prince Ovolensky’s request, Alexander Siloti welcomed Eugene Istomin and his parents with open arms by the end of 1931. He listened to the little boy accompanying his mother in Russian folk songs. That was enough to convince Siloti to take him as a student. His only requirement was that there should be no commercial exploitation of the young prodigy.

Kyriena, the only one of Siloti’s six children who had pursued a musical career, was in charge of teaching him theory and solfege, as well as the basics of piano technique. She also taught him to write Russian, speak French and say a few words in German. Alexander Siloti, for his part, often invited him to come and sit at the piano next to him, playing duets, inventing innumerable games, or recounting the history of music, which he illustrated at the keyboard. At times he also played the clown, sticking out his tongue and making faces, or contorting his legs behind his head! Istomin was treated like a grandson, with great affection and generosity, for six years. He often spent most of the day there, and occasionally he would spend the night as well.

The separation

In the spring of 1937, George Istomin became seriously concerned about his son’s education. He saw that Gary Graffman, the son of Russian emigrants whom he knew well, spent long hours at the piano. Eugene was three years older than Gary, yet Siloti only asked him to practice for an hour and a half a day. As time went by, this seemed even stranger to him. He wondered if Siloti, at 74, had perhaps lapsed into senility. It was said that he always set a place at the table for Liszt.

In order to leave Siloti and start looking for another teacher, Eugene’s father needed financial support. He appealed once again to the solidarity of Russian emigrants. Boris Sergievski, George Istomin’s comrade-in-arms in the Tsar’s Air Force, had become a brilliant test pilot. He offered $5,000 to allow young Eugene to pursue his musical studies.

In order to leave Siloti and start looking for another teacher, Eugene’s father needed financial support. He appealed once again to the solidarity of Russian emigrants. Boris Sergievski, George Istomin’s comrade-in-arms in the Tsar’s Air Force, had become a brilliant test pilot. He offered $5,000 to allow young Eugene to pursue his musical studies.

The separation from Siloti was cruel. George Istomin did his best to express his gratitude and tried to explain that it was time for his son to continue his education in a more formal setting. Alexander Siloti’s reaction was very noble. He gave Eugene a photo with a touching dedication, and wished him every success. However, in his heart of hearts, he was devastated because he was sure that Eugene was the great talent he had been expecting for so long, and that, under his tutelage, he would have become one of the greatest pianists of his day. It was also utterly heartbreaking to have this young boy who had become a part of their family taken away from them. Many years later, Kyriena admitted that she and her father had never forgiven Eugene’s parents.

In the past, when he was teaching Sergei Rachmaninoff, Siloti was a supporter of the traditional approach which involved long and tedious technical practice. However, personal experience caused him to change his mind. Kyriena Siloti was surprised to see that her father practiced much less than any other pianist and never stayed at the piano for more than half an hour at a time, saying that he was tired. She pointed out to him that she herself was not tired after half an hour! He replied: “It’s because you don’t practice, you only play”. By this time, he was persuaded that quality of practice was much more important than quantity. It was this conviction that drove his pedagogical approach and explained why he required Istomin to spend so little time at the piano. It would be fascinating to see what would have happened if Istomin had stayed on with Siloti!

Epilogue

Eugene loved Siloti, who was like a real grandfather to him. He only followed his father’s decisions, but he was aware of the drama that had taken place. He could not help feeling in some way responsible, and this led him to bury many memories in the depths of his subconscious which would resurface years later when talking with Kyriena. In the 70s, she casually mentioned their visiting Rachmaninoff forty years ago, and suddenly all the memories came flooding back. On a later visit, as Kyriena was approaching her 95th birthday, Istomin offered to organize a celebration. She refused but told him how much she would like something to be done to perpetuate her father’s memory. .

Istomin decided to organize a “benefit concert” to create a scholarship in Siloti’s name at Juilliard, where Siloti had taught for so long. The concert took place on November 5, 1990 at Juilliard, unfortunately after Kyriena’s death.  Istomin was able to mobilize several generations of great pianists linked to Russia: Shura Cherkassky, Alexander Slobodyanik, Alexander Toradze, Vladimir Feltsman, Gary Graffman, John Browning, and to arouse the interest of the media. Mstislav Rostropovich participated, playing a movement from the Rachmaninoff Cello Sonata (which Siloti had formerly played with Casals) and conducting the Juilliard School student orchestra in one of the Bach concertos for 3 pianos. The event was widely covered by the media, and excerpts of the concert were broadcast by CBS Sunday Morning.

Istomin was able to mobilize several generations of great pianists linked to Russia: Shura Cherkassky, Alexander Slobodyanik, Alexander Toradze, Vladimir Feltsman, Gary Graffman, John Browning, and to arouse the interest of the media. Mstislav Rostropovich participated, playing a movement from the Rachmaninoff Cello Sonata (which Siloti had formerly played with Casals) and conducting the Juilliard School student orchestra in one of the Bach concertos for 3 pianos. The event was widely covered by the media, and excerpts of the concert were broadcast by CBS Sunday Morning.

Document

Alexander Siloti playing Liszt and Rachmaninoff at home in the 1930s. A very moving recording despite the poor sound.