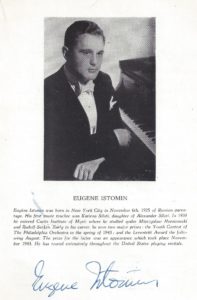

This text was written by Eugene Istomin in 1990 at Isaac Stern’s request for a reissue of the Trio’s recordings as a part of a Stern collection. It was published by Sony in 1990

The history of the Trio goes back to the year 1950. The place was Prades in the eastern Pyrenees in France. The occasion was a festival commemorating the bicentenary of J.-S. Bach’s death. The focus of the event was Pablo Casals, who had, through the persuasion of Alexander Schneider, agreed to lead the festival and make music again after a self-imposed exile, assumed final.

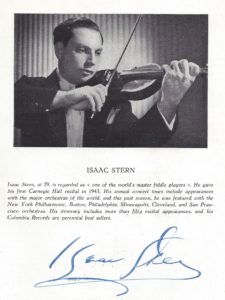

The two youngest soloists invited to participate were Isaac Stern and I. Schneider had convinced Casals that such a contact between generations spanning nearly a century would be mutually interesting and beneficial – especially to us. Events proved this true beyond any of our wildest dreams. Lives were changed – friendships were formed – musical alliances forged and projects conceived – among them our trio and the recordings of this collection. It also marked the beginning of the long lasting collaborations between Isaac and me, which included the complete Beethoven Piano-Violin Sonatas recordings of 1984.

How did this come about? The extraordinary generative spirit of Casals was a catalyst that Stern and I were both young enough, yet experienced enough, to make the most of. We possessed a veritable musical treasure trove and we knew it. It served as a fount of inspiring ideas, revelations, and the affirmation of our individual worth as musicians.

How did this come about? The extraordinary generative spirit of Casals was a catalyst that Stern and I were both young enough, yet experienced enough, to make the most of. We possessed a veritable musical treasure trove and we knew it. It served as a fount of inspiring ideas, revelations, and the affirmation of our individual worth as musicians.

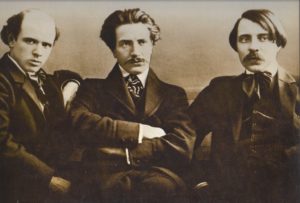

Affirmation for me because as a 24-year-old pianist, much coddled, but also much criticized, it meant a lot to be rated as a major artist by an historic musician of Don Pablo’s stature. As for Stern, who arrived basking in the glow of a London triumph, with projects of major recordings with Sir Thomas Beecham of the Brahms and Sibelius Violin Concerti, he was further inspired when Casals immediately compared him to Eugene Ysaÿe, whom the Maestro considered the king of all the great violinists he had known from Sarasate and Joachim to Kreisler and Heifetz. For two brash, young Americans in France in 1950, we were not doing too badly!

Though we played and recorded a trio in that festival, the Bach Trio Sonata for violin and piano with John Wummer, the great flutist of the New York Philharmonic. Stern also recorded the A Minor Violin Concerto and the Oboe and Violin Concerto with Marcel Tabuteau under Casals’ direction while I played the cembalo part of the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto with Joseph Szigeti and John Wummer conducted by Casals as well as a solo toccata.

For the next two years, Stern and I returned to play and record with Casals as trio partners and in other formations. It was not until the 1952 Festival, that Stern and I played a sonata together for the first time (the Schumann A minor) and we also performed a Brahms Trio together with Casals.

There is no doubt in my mind that an already strongly ingrained chemistry between Stern and myself was enhanced by our collaborations with Casals. We wanted to follow up in the “real world” and soon began to talk about joint musical projects beyond Prades. Dare we entertain the idea of forming our own “all-star-trio” in the mode of Cortot-Thibaud-Casals or, more recently, Rubinstein-Heifetz-Piatigorsky? Why not? Trio music is, after all, an exercise in individual projection in powerful triplicate rather than the more self-effacing metamorphic blend of a string quartet. In point of fact, the melding in trio-playing is a relatively simple technical matter of balance, providing the players are congenial – a critical if of course! What can be especially gratifying in this combination is the appropriation, compelled by the music, of the playing of your partners as your own, rather than sacrificing your personality to theirs.

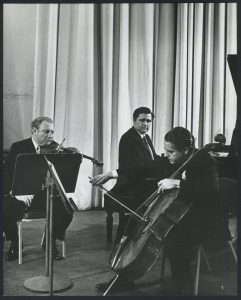

Obviously, Stern and I could not export the monumental Casals from Prades as our trio partner, so we needed someone in our own generation. We chose Leonard Rose, whom many considered the finest cellist in America. He had begun his solo career in 1951 after an illustrious period as first cellist of the Cleveland and New York Philharmonic Orchestras. Stern and Rose had already performed the Brahms Double Concerto in concert and ultimately recorded it with Bruno Walter and the New York Philharmonic (a very famous recording). Rose and I had played a few joint recitals as well and had established a very high mutual regard. In ensemble string playing, Stern and Rose always maintained that the one technical cohesion that was most important and rare was the fusion of vibratos. Often they must sound as one or interlock in phrases as a single, seamless line. So they should match – and match they did – fitting like hands in gloves. That sealed it. Rose agreed to join us in Chicago at the Ravinia Festival in the summer of 1955. After performing as soloist with the Chicago Symphony, we gave a series of sonatas and trios concerts. This was our shake-down cruise. Having thus tested the waters, we found some of the critical response in Chicago’s press icy indeed. Very much sobered, we decided to return to our solo careers and dream on a few more years about our version of “The Trio”. In fact during the next five years, Stern and I had occasion to play several times together – and mainly again at events involving Pablo Casals – and we performed two trios with him in 1959 at the Puerto Rico Festival.

Biding our time and awaiting the right occasion to regroup, we finally set sail toward our goal again in 1960-1961 and stayed the course – this time for good. The occasion was the first Israel Festival where, amongst other things, we inaugurated the old Roman Herod Atticus Theater in Caesarea playing the first notes heard there since antiquity. Later, we played the Beethoven Triple Concerto in New York, in Carnegie Hall, with Alfred Wallenstein conducting the Symphony of the Air. Now the media response was much warmer, confirming our credibility as a serious trio. We then decided to apportion a few weeks a year for a limited number of engagements in North America and Europe: the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962, the Montreal World’s Fair in 1967, the Edinburgh, Lucerne, Menton, Aix-en-Provence Festivals, to mention a few. We played more or less annually in Carnegie Hall, Chicago’s Orchestra Hall, Boston’s Symphony Hall, Paris’s Theâtre des Champs-Elysées and London’s Festival Hall; and on several university concert series in the United States.

The most strenuous and perhaps harrowing year for us was Beethoven’s Bicentenary year in 1970 when we stayed together for six months, playing complete cycles of thirty-one works of piano chamber music, sonatas, trios, piano quartet, etc., in London, Paris, Switzerland, Buenos Aires and Carnegie Hall. In the fall of 1971, we played the first recital in the Concert Hall of the newly inaugurated John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts (we had performed at the White House in 1962), and finally in Tokyo and other cities in Japan. It was during this time that we recorded the complete Beethoven Trios, two piano and cello sonatas, released much later. Stern and I also recorded two of the piano violin sonatas, but did not complete our full project of the complete sonatas until 1984.

I must say that while we laughed a lot, bickered and quarreled quite a bit – once or twice very seriously – our basic unity on musical ideals never wavered – nor did our capacity to attain that most intimate of communications which musicians can have with one another. When you have that, minor differencies are worth enduring.

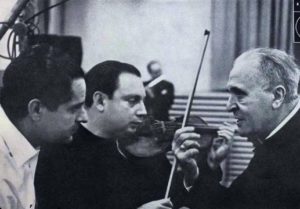

In later years, when meeting after we had fulfilled our solo commitments, it only took a few bars to re-ignite that unlearnable, unrehearsable spark between us. Not that we were certain about everything we did. To the contrary, we very much sought and valued the comments of colleagues, modest and not so modest. An example: George Szell – not known for his sparkling sense of humor – once asked us, at a rehearsal in Cleveland of the Beethoven Triple Concerto following our successive solo entrances, which of our differing tempi was the right one for his orchestra to continue with!! This was helpful, so that, when the time came to record the work with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, we had gotten our tempi in line, thus avoiding yet another sarcastic query! Szell also had useful and much more complimentary comments to make in Edinburgh about our work on the Schubert Opus 100 Trio. Arthur Rubinstein, most generouly, helped us with positive comments when we ran through the same trio for him during a Lucerne Festival. Sasha Schneider often offered his inimitable, sometimes uninvited, but always wise comments. And then, of course, there was Maître Casals. I particularly recall his observation on the tempo of the first movement of the Ravel Trio (faster than many take today) which the composer himself had heard Cortot-Thibaud-Casals play more than once.

When recording, we were veritable fiends about perfection and headache to our producers and engineers, as each of us was, of course, being extremely protective of his own sound. We knew just what we wanted and did not want. It must be said, however, that we also cared greatly about our partners’ sound since they were felt to be extensions of our own. For example, we began recording the Schubert Opus 100 in Wintherthur, Switzerland, and later abandoned it until we returned to New York. The sound, the strings, piano – all was wrong. In New York, with the help of our recording director and capable engineers, we found the kind of balance and ambiance that gave us the freedom to make music our way.

When recording, we were veritable fiends about perfection and headache to our producers and engineers, as each of us was, of course, being extremely protective of his own sound. We knew just what we wanted and did not want. It must be said, however, that we also cared greatly about our partners’ sound since they were felt to be extensions of our own. For example, we began recording the Schubert Opus 100 in Wintherthur, Switzerland, and later abandoned it until we returned to New York. The sound, the strings, piano – all was wrong. In New York, with the help of our recording director and capable engineers, we found the kind of balance and ambiance that gave us the freedom to make music our way.

In summing up, we had a fantastic time. Apart from the enormous fun of it, we may have introduced into the music scene of our time the idea of the virtuoso trio, of demonstrable staying power and a certain allure, thus encouraging the formation of several younger world-class trios as a result of our highly visible and successful efforts. We hope these recordings will hold as documents of our shared musical experience.