The project of the Trio Istomin-Stern-Rose to perform the complete Beethoven chamber music with piano (thirty-one works) was one of the most significant events in the rich celebration of the bicentennial of Beethoven’s birth, and one of the most widely publicized. They had planned to do it four times in eight concerts. It was a great first in the history of musical performance, a challenge that had never before been met!

Before the four full cycles which were scheduled in fall, the Beethoven adventure of the Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio began in Minneapolis on May 9. By the end of June, they had already toured the United States, participated in the Puerto Rico Festival, spent two weeks in Buenos Aires and stayed in Brazil. In July, the members of the Trio were mainly committed to their own concerts. Nevertheless, they joined to perform the Beethoven Triple Concerto (at the Hollywood Bowl and in Saratoga, the Philadelphia Orchestra’s summer residence) and to record the only trio they had not yet recorded, the Opus 70 No. 1 “Ghost”. In August, they went to Israel and, after a short stop in Edinburgh, they started the marathon of the complete cycles in London on September 13th, at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, They achieved three in Europe, alternating London, Paris and Switzerland (divided between Zurich, Bern, Basel and Vevey) until November 5. As soon as they returned to the United States, they immediately embarked on a fourth and last one, at Carnegie Hall, between November 11 and December 12. Within seven months, Istomin, Stern and Rose gave some seventy Beethoven concerts. In addition, there were countless requests from all medias!

The adventure had not begun under the most auspicious of circumstances. Istomin was exasperated by Columbia’s tergiversations. In 1965, he had signed a four-year contract for two concertos and four solo piano records. Only the two concertos (Brahms’ Second in 1965, and Beethoven’s Fourth in 1968) and a solo piano disc (Schubert’s Sonata in D major D. 850 in 1969) had been released. Negotiations for renewal continued to drag on. Istomin wanted at least to record the Beethoven Emperor Concerto. Columbia eventually refused, confining him to chamber music. In addition to completing the trios, Columbia demanded that he record all the Beethoven sonatas for both violin and cello. It was a considerable effort (12 LPs in total) and a frustrating situation which might damage his reputation and career as a soloist. Istomin then decided to abandon the sonatas (four had already been recorded in July and August 1969) and to limit himself to the trios. This was a big disappointment for Stern and even more so for Rose, who considered this integral to be the ultimate achievement of his career and who felt betrayed. Stern and Rose understood Istomin’s anger, but they considered themselves to be unwilling hostages in this conflict.

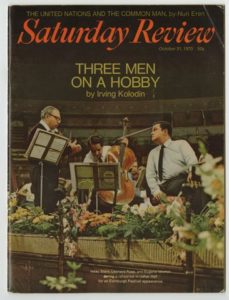

The Trio’s reunion in early May happened in a rather heavy atmosphere. The friendly euphoria of the Trio’s early days was over. Getting along for seven months of uninterrupted tour would not be easy, especially since the challenge was tremendous: eight programs to be prepared and subsequently performed in very exposed places, and frequently broadcast, recorded or filmed. In addition to this, it was necessary to add the fatigue and tension due to the accumulation of rehearsals, trips, concerts and interviews. “Three screaming lunatic egomaniacs together for three months” is how Istomin described the Trio on the eve of leaving for Israel and Europe. The image may seem caricatural, but one has to admit that the human functioning of the Trio was not at all simple.

In High Fidelity, Robert Jacobson sketched a collective profile, entitled The Intellectual, the Gambler and the Corporate Man: “As musicians, as individuals, Istomin, Stern and Rose dwell in three vastly different worlds. Istomin is the self-imposed pessimist (and may we say it? – sometimes sourpuss), the intellectual, the seeker after the impossible through sweat and toil, a man of integrity – and the moving force in what was a highly concentrated period of activity, the 1970 Beethoven Bicentennial Trio cycle. Stern, on the other hand, is the optimist, the showman, the chance-taker, the gambler who lives dangerously but confidently in the unknown. Rose forms the fulcrum for these two opposites: steady, business-like, meticulous, and punctual.” Clearly, Jacobson was unaware of Rose’s volatile temperament.

As Istomin’s duty was significantly heavier than that of his colleagues, he was given the responsibility of dividing the thirty-one works into eight programs, a difficult task, as Rose explained to Radio Canada: “Mr. Istomin has done an enormous amount of research for that. First of all, you must remember that he is going to play all the pieces. I get to only listen to the ten Violin Sonatas. Mr. Stern gets to listen to the five Cello Sonatas and the three sets of variations. Mr. Istomin plays everything. And because he will play everything, I must say, he has perhaps put in the most effort in arranging the programs, but of course subject to all of our approvals, which we have given. I think we now have marvelous programs.”

Istomin had to simultaneously practice for himself and be available to his partners. Thornton Trapp, who was accompanying the Trio, organizing the trips and turning pages for Istomin, kept a diary throughout the adventure. He felt that Istomin’s life was a nightmare: “Eugene went off to rehearse with Lenny, who like Isaac makes too many demands on him, the former by endless rehearsal of pieces he knows inside-out, and the latter, by relearning or even learning pieces, both involving an intolerable number of repetitions of the piano part. It is not surprising that Eugene is sometimes depressed, not only by this exploitation but by the continuous efforts made, by him, in various ways, mostly very subtle, to help the two reach their optimum.” Trapp was never short of ideas and humor to remedy this situation: “An obvious solution of this problem is for Eugene to record the piano parts, hand the tapes over to the two, who will then be able to practice twenty-four hours a day with the help of a piano.”

During this Beethoven marathon, Istomin was often very tense, and sometimes depressed, due to overwork and the frustration engendered by his usual perfectionism. He was also deeply concerned about his father’s health. His parents had joined him in Israel and then in London. After a first illness in Israel, Istomin’s father had to be hospitalized in England and undergo a transfusion. Upon his return to the United States, he underwent surgery for what was believed to be a stomach ulcer. Fatigue and anxiety finally brought trouble to Istomin’s back. For several weeks, he managed to cope with the pain and cancelled only one concert, for which Isaac was not ready anyway. Relations between the three musicians were sometimes difficult. Trapp offered a relevant analysis: “Eugene’s proposals are generally very fair and always take others into account. But the way he presents them does not always make them easily acceptable. His intransigence is great: it ranges from punctuality to musical ethics. He doesn’t mince his words and, unlike Isaac, he finds it difficult to admit defeat in a discussion. Isaac noticed that Eugene had never learned to apologize, but that this tour puts him on the right track.”

On the musical side, things were not so simple either, according to Trapp’s report: “It’s so ironic that the three need each other in so many ways. For instance, Lennie and Isaac couldn’t replace Eugene, for there is no other artist able and willing to do what he does. Eugene and Lenny need Isaac’s popularity for bookings, which only Isaac could make. Artistically, Eugene having learned so much from early years with Casals and Busch, has so much to give Isaac, who after some resistance will perhaps accept it, and has much to teach Lennie as well. But Lenny is a teacher himself, and therefore resists tuition, at least from Eugene, whose manners probably makes it difficult for Lennie – though sometimes he will accept a little suggestion, which comes to him by the way of Isaac. But whatever divides them is at the moment not as strong as the music which unites them.”

In fact, one may wonder whether these tensions were not the most favorable atmosphere to meet Beethoven’s demands! Istomin pointed it out to Jacobson: “It is really the conflict that produces music, not unanimity of personalities.” And Stern added: “If you don’t have a strongly personal view-point, you don’t have an artistic view point.” The best demonstration was that quarrels had no harmful consequences on their playing, even when they broke out just before the concert! Trapp recounts Istomin’s great wrath after Rose had broken the protocol for going onstage: “His face was black with outrage and he looked twice his normal size. He refused to acknowledge the applause, satirically bowing to his colleagues onstage and said that it was the last of their concerts.” What was fascinating, however, was that Eugene’s playing was not affected. Istomin had a remarkable ability to forgive and forget. Trapp observed: “Once again, the three survived, a not infrequent minor miracle. Truly, the bonds of love-hate can take a lot of breaking.” Istomin was mainly upset by Stern, his delays and lack of practice: “Often he would get me so angry with him and so competitive by goading me. My response is of competitive nature.” This had the effect of exalting Istomin to even greater heights, and generated moments of exceptional musical tension. This was particularly noticeable in some works such as the Trios Opus 70, the Violin Sonata Op. 30 No. 2 and especially the Kreutzer Sonata. Trapp noted that the finale became “more of a duel than a duet”, in the same way as the rivalry between Bridgetower and Beethoven when this sonata was composed.

Of course, there were also many happy moments to share. From the outside, this tour looks like a succession of triumphs ! Trapp was amused to note that “standing ovations become increasingly common”. As a fine musician, he also reported the many high musical achievements. Beyond this intense sharing, there was also the feeling of experiencing an unprecedented adventure. It was in Argentina that they felt most like pioneers. No major trio had ever before performed in Buenos Aires. They started off with a tremendous success in the huge Teatro Colón, with its fabulous acoustics. Istomin had to sign countless records of the Schumann Concerto, recently published in this country and crowned “Recording of the Year”. They then performed several times in two gigantic cinemas which were absolutely packed. Their concerts were scheduled at 10:30 p.m. or 11:00 p.m., after the last projection, and the audience continued to eat ice cream, candy and popcorn until the arrival of the musicians! Stern miraculously transformed a very mediocre orchestra into a very good one that gave its utmost best in a televised concert, with three Beethoven concertos in succession. Istomin, Stern and Rose even went through a coup d’état, when General Juan Carlos Onganía was overthrown by his former friends of the Military Junta on June 8th.

The complete cycles given in Europe and the United States did not have the same innovative flavor, but they were also very rich in emotions and multiple events. The opportunities for laughing, especially with a little hindsight, were not lacking: Homeric journeys, forgotten, lost or mixed-up scores, bad hotels… After-concert events were unpredictable: sometimes a stale sandwich eaten alone, often gourmet dinners with friends from all over the world, or short nights after endless discussions over a bottle of whisky. Less amusing were the vicissitudes of pianos. In Zurich, it even turned into a disaster once: a brilliant and harsh sound, making any nuance of pianissimo or even piano impossible. This revived the old quarrel over the opening of the piano lid for chamber music. Even though it was absolutely unintended, Istomin was accused of drowning out his colleagues! Less funny too, were the inevitable health problems due to fatigue and stress: Istomin had long suffered from his back, endured a toothache, a bad cold, and several bouts of indigestion. These are small inconveniences in everyone’s daily life, but discouraging worries in a touring life, especially for a huge tour like this one!

Fortunately, success was rampant. In London, the Trio broke the Queen Elizabeth record for a series booking! Although the concert was announced as sold out, several hundred people came every night with the faint hope of finding a resold ticket. The audiences were very enthusiastic, sometimes frenzied. In Paris, Istomin and Stern were almost forced to give an encore at the end of the first part, after a sublime performance of the Sonata Opus 96. The passion was such that when Stern announced on stage that the Kreutzer Sonata would be postponed to another night, the audience shouted and protested for more than one minute, which did not prevent it from frantically applauding at the end of the concert, after a flamboyant Trio Opus 70 No. 2. The Trio caused a buzz! All the medias were involved. The Argentinian, French and English television companies filmed numerous concerts and studio performances, as well as profiles of the members of the Trio. In Paris, a television crew even came to shoot Istomin having lunch with his friends the Chatellier family, who had welcomed him during his first stay in Paris in 1948, while he was enjoying a delicious quiche Lorraine. They were nearly pop stars!

The critics were often ecstatic, with the somewhat annoying exception from part of the English press. The Times was systematically negative, both out of anti-Americanism and frustration at the fall of two of its deep-rooted prejudices: chamber music does not attract audiences; and three great soloists are unable to form a coherent trio. Trapp, who knew his compatriots well, was convinced that some English critics reproached Istomin, Stern and Rose for being too self-confident at the press conferences. He imagined their inner thoughts: “It’s for us to judge, not you. You presume too much, and you are not quite as good as you think”. Two critics were particularly negative towards Istomin, in retaliation. They were members of the committee which had awarded Istomin the Harriet Cohen Award for the best recital of the season. It was a unique privilege for an American pianist, but Istomin had not made the effort to come and receive his Award in person and he had not shown the gratitude they expected.

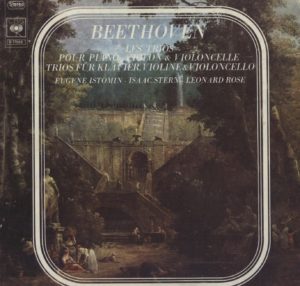

The final outcome of the great challenge proved to be extremely positive! The publication of the box set of the complete Trios was a huge success all over the world. It was awarded many prizes, including a Grammy Award. Istomin appeared to be at the top of his artistry and repeatedly received the compliments that mattered most to him, from musicians and connoisseurs. As usual, he preferred not to indulge in blissful satisfaction and refused to be wax ecstatic over the audience’s sudden passion for chamber music: “We’re just the coffee-table Trio”. It was certainly true that the media and the public were more motivated by the curiosity of seeing three stars together than by a love for chamber music. But it is also true that this event, and all the media attention that went with it, helped to introduce many people to chamber music. It was a wonderful achievement for all three of them, and the last word can be left to Isaac Stern: “The musical concept repays you for any sacrifice of ego. The recompense is the finality of involvement in music at the highest level – and exaltation you can touch. I have been excited and uplifted and ennobled -although that’s a pretentious word – by performances. Yes, we have to compromise, but when you play music like this, in the final analysis you play it for yourself. I could have had an easier six months, with more remuneration and personal glory, but I didn’t wish it. The Beethoven cycle was a reaffirmation of a belief in music, and this needs restating from time to time.”

Documents

Beethoven, Allegretto WoO 39. Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern, Leonard Rose. Concert of October 8, 1970.

.

Beethoven, Trio in E flat major Op. 70 No. 2. Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern, Leonard Rose. Paris, October 1970, French Television studio.

.

Beethoven, Triple Concerto in C major op. 56, first movement. Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern, Leonard Rose. Casals Festival Orchestra, Pablo Casals. Concert in San Juan of Puerto Rico on May 31, 1970. A very moving document despite the quality of image and sound.

.

Concerts and recordings during the Beethoven Year

April 2. New York, Columbia Studio. Recording of the Trios WoO 38 and 39

May 7: New York, Columbia Studio. Recording of the Variations Op. 44

May 9. Minneapolis. Program to be found.

May 10. Saint Paul. Cello Sonata No. 4; Violin Sonata No. 10; Trio Opus 1 No. 1.

May 11: Princeton. Variations Op. 44 ; Trio Op. 1 No. 1; Brahms, Trio No. 2.

May 12. New Rochelle. Cello Sonata No. 4; Violin Sonata No. 10; Trio Opus 1 No. 1.

May 13. New York, Columbia Studio. Recording of the Trio Op. 1 No. 1.

May 14. Manchester, Capitol. Variations Op. 44; Trio Op. 1 No. 1; Brahms, Trio No. 2.

May 16. Chicago. Program to be found.

May 19. Claremont (California): Cello Sonata No. 5; Violin Sonata No. 10; Brahms, Trio No. 2.

May 21. Los Angeles. Program to be found.

May 23. New York, Metropolitan Museum. Variations Op. 44; Brahms, Trio No. 2; Trio Op. 70 No. 2.

May 25. Philadelphia. Trio WoO 39. Cello Sonata No. 5; Violin Sonata No. 10; Trio Op. 70 No. 2.

May 26. New York, Columbia Studio. Recording of the Trio Op. 70 No. 2 (3 first movements).

May 27. New York, Columbia Studio, Recording of the last movement of the Trio Op. 70 No. 2, and redoing a movement of the Trio Op. 1 No. 1.

May 31. Puerto Rico, University. Piano Concerto No. 3; Triple Concerto. Casals Festival Orchestra, Schneider (Concerto No. 3) and Casals (Triple).

June 1. Puerto Rico, University. Cello Sonata No. 5; Violin Sonata No. 10; Trio Op. 70 No. 2.

June 7. Buenos Aires, Teatro Colón. Trio Op. 1 No. 3; Trio Op. 70 No. 1; Trio Op. 70 No. 2.

June 9. Buenos Aires, Coliseo Cinema. Trio WoO 39; Cello Sonata No. 2; Violin Sonata No. 10; Trio Op. 1 No. 1.

June 11. Buenos Aires, Coliseo Cinema. Variations Op. 44; Cello Sonata No. 3; Violin Sonata No. 4; Trio Op. 11

June 15 & 16. Buenos Aires, Broadway Cinema. Piano Concerto No. 3; Triple Concerto. Wagner Association Orchestra, Pedro Calderón.

June 18. Buenos Aires. Coliseo Cinema. Cello Sonata No. 4; Violin Sonata No. 7; Trio Op. 97 “Archduke”.

Late June. Concerts in Brazil. Dates and programs to be found, excepted June 27.

June 27. Guanabara. Triple Concerto. Orquestra Sinfonica Brasileira. Isaac Karabtchesky.

July 25. Los Angeles, Hollywood Bowl. Triple Concerto (+ Chopin, Concerto No. 2). Los Angeles Philharmonic, André Previn.

July 25. Saratoga. Piano Concerto No. 4, Triple Concerto. Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy.

August 15. Jerusalem, Binyenei Ha’ooma. Cello Sonata No. 1; Violin Sonata No. 6; Trio Op. 97 “Archduke”.

August 17. Caesara, Roman Theater. Trio Op. 1 No. 3; Violin Sonata No. 8; Variations on Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen »; Trio Op. 70 No. 1.

August 20. Caesara, Roman Theater. Triple Concerto. Alexander Schneider

August 22: Jerusalem. Triple Concerto. Alexander Schneider

Other dates and programs to be found.

Early September. Paris, Studio of the French Television. Filming of the seven Trios.

September 13. London, Queen Elizabeth Hall. Trio Op.70 No.1; Violin Sonata No. 8; Cello Sonata No. 5; Kakadu Variations Op. 121a.

September 15. London, Queen Elizabeth Hall. Violin Sonata No. 1. Cello Sonata No. 4. Violin Sonata No. 7. Trio Op. 1 No. 1.

September 17. London, Queen Elizabeth Hall. Trio WoO 39; Cello Sonata Op. 17; Violin Sonata No 4; Variations on “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen”; Quintet for piano and winds Op. 16.

September 22. London, Queen Elizabeth Hall. Variations on Judas Maccabeus ; Violin Sonata No. 2 & 3; Trio Opus 1 No. 3.

September 24. London, Queen Elizabeth Hall. Concert postponed in November

September 28. Zurich, Tonhalle. Program to be found.

September 29. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Trio Op. 70 No. 1; Violin Sonata No. 8; Cello Sonata No. 5; Kakadu Variations Op. 121a.

September 30. Paris, Studio of the French Television. Filming of the Kakadu Variations Op. 121a.

October 2. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Violin Sonata No. 1; Cello Sonata No. 4; Violin Sonata No 7; Trio Op. 1 No. 1.

October 4. London, Queen Elizabeth Hall. 6th concert. Program to be found.

October 6. London, Queen Elizabeth Hall. Variations Op. 44. Violin Sonata No. 6; Cello Sonata No. 1; Trio Op. 70 No. 2.

October 8. Queen Elizabeth Hall. Trio WoO 39; Variations sur “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen”; Violin Sonata No. 10; Trio Op. 97 “Archduke”.

October 11. Zurich, Tonhalle. Program to be found.

October 12. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Violin Sonata No. 5; Cello Sonata No. 3; Trio Op. 1 No. 2.

October 16. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Trio WoO 38; Cello Sonata Op. 17; Variations op. 66; Violin Sonata No. 4. Quartet Op. 16 bis (with Bruno Pasquier).

October 19. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Violin Sonata No. 2; Variations on Judas Maccabeus; Violin Sonata No. 3; Trio Op. 1 No. 3.

October 22. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Trio Op. 11. Cello Sonata No. 1; Trio Op. 70 No. 2 (replacing the Kreutzer Sonata)

October 25. Zurich, Tonhalle. Cello Sonata No. 2; Trio op. 11; Violin Sonata No. 9 “Kreutzer”

October 26. Basel, Casino. Cello Sonata No. 2; Trio Op. 11; Violin Sonata No. 9 “Kreutzer”

October 28. Bern. Cello Sonata No. 2; Trio Op. 1; Violin Sonata No. 9 “Kreutzer”.

October 30. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Variations Op. 44. Cello Sonata No. 2; Violin Sonata No. 9 “Kreutzer”.

November 1. Basel, Casino. Program to be found.

November 2. Paris, Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Trio WoO 39; Variations on “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen”; Violin Sonata No 10; Trio Op. 97 “Archduke”.

November 4. Vevey. Trio WoO 39; Trio Op. 1 No. 2 ; Violin Sonata No. 9 “Kreutzer “; Trio Op. 70 No. 1.

November 5. Paris, Studio of the French Television. Filming of the Variations Op. 44.

November ? Postponed concert in London. Date and program to be found.

November 11. New York, Carnegie Hall. Kakadu Variations Op. 121a; Violin Sonata No. 1; Cello Sonata No. 4; Trio Op. 70 No. 1

November 14. New York, Carnegie Hall. Cello Sonata No. 2; Trio Op. 11; Kreutzer Sonata.

November 18. New York, Carnegie Hall. Trio WoO 39. Cello Sonata Op. 17 Violin Sonata No 4. Variations on “Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen”; Quintet for piano and winds Op. 16.

November 25. New York, Carnegie Hall. Violin Sonata No. 2 ; Variations on Judas Maccabaeus; Violin Sonata No. 3; Trio Op. 1 No. 3.

November 28. New York, Carnegie Hall. Violin Sonata No. 5; Cello Sonata No. 3; Trio Op. 1 No. 2.

December2. New York, Carnegie Hall. Variations on “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen”; Violin Sonatas No. 8 & 7 ; Trio WoO 38 et Op. 1 No. 1.

December 5. New York, Carnegie Hall. Variations Op. 44; Violin Sonata No. 6; Cello Sonata No. 1; Trio Op. 70 No. 2.

December 12. New York, Carnegie Hall. Cello Sonata No. 5; Violin Sonata No. 10; Trio Op. 97 “Archduke”.