‘’My friend and long-time partner, Isaac Stern, is the great communicator among the violinists of our time. The goals he pursues and achieves by the force of his talent and personality surpass perfection. There is a largeness – a grandeur in him – that is made accessible to all by his easy warmth. He seems to say with his playing and his life ‘I need to speak to you’. He does.’’

The relationship between Isaac Stern and Eugene Istomin is extensively covered in the articles about the legendary trio they formed with Leonard Rose. Here are some additional elements on the events and ideas they shared, aside from the trio.

The first contacts

Istomin and Stern first met in 1944 at the home of a mutual friend, pianist Sidney Foster, who had won the 1940 Leventritt Competition and was beginning a promising career. Istomin had been impressed by Stern’s personality, his self-confidence, his frankness, and the feeling he gave of living in a constant whirlwind. Stern said: “We must do some music together, I’ll call you.’’

Stern did not call, and the two men only met two years later at Lewisohn Stadium, on August 12, 1946, for the final concert of the New York Philharmonic summer season. The program was dedicated to Beethoven: Istomin played the Fourth Concerto and Stern the Violin Concerto. Both received mediocre reviews (their performances were brilliant but too superficial and lacked maturity). However, the audience of 17,000 spectators cheered them on and Istomin had to give two encores.

It was at the first Prades Festival, in 1950, that they really got to know each other. Alexander Schneider had suggested inviting two young musicians to take advantage of and, in turn, transmit this exceptional experience. He chose Eugene Istomin and Isaac Stern, who were then respectively 24 and 29 years old. The sixth and last chamber music concert was almost entirely entrusted to them, an extraordinary honor. After the Trio Sonata in G major BWV 1038 with flutist John Wummer, they alternated, Stern playing the First Sonata and Second Partita for solo violin, and Istomin the Toccata in E minor BWV 914 and the Partita in C minor BWV 826. This was their first collaboration, and there were to be nearly three hundred others until 1997, in Evian, when they performed the Beethoven First Violin Sonata and the Brahms Piano Quartet Op. 25 with Bashmet and Rostropovich.

The importance of Casals

Meeting Casals profoundly changed the lives of Istomin and Stern, far beyond anything Schneider could have even imagined. For Istomin, this is a matter of course (the story of their relationship can be found in the chapter specially dedicated to Casals), but it also holds true for Stern. Casals had been very enthusiastic about the talent of the two young musicians. He immediately compared Stern to Ysaÿe, which was probably the greatest compliment he could give. (Funnily enough, in 1953, Isaac Stern would play the role of Ysaÿe in Mitchell Leisen’s film Tonight We Sing, inspired by the life of the famous impresario Sol Hurok.)

In his autobiography, My First 79 Years, Stern explained that it was very difficult for him to describe the shock of meeting Casals: “The best image I’ve been able to come up with involves a high brick wall and a garden. Imagine yourself suddenly coming upon such a wall, not knowing that beyond it lay an exquisite garden. What Casals did was open a door into the garden; you entered and suddenly found yourself amid colors and scents you never dreamed existed. He revealed what might be accomplished once you were inside the garden. But how many of the colors and scents you could make your own, giving greater power to your musical imagination – that was your responsibility.” Sasha Schneider stated that Stern probably wouldn’t have been such a great musician without Casals: “He certainly learned more from Casals than anyone else who was around him and he took the best of it.” In particular, he became aware of the need to vary his vibrato infinitely in breadth and speed, according to expressive requirements. The temptation is always great for violinists to use a permanently fast vibrato that gives more brilliance to their sound but which limits the diversity of colors and emotions, and eventually becomes tiresome.

In 1951, Stern was only able to participate in the first two concerts of the festival, which took place in Perpignan, due to other engagements. In August, he toured Israel and met Vera Lindenblit. Love at first sight was such that they married 17 days after meeting! In September, they went to Prades to visit Casals and joined Istomin and Schneider who were just back from a trip to Greece. The reunion was joyous and resulted in a profusion of music making.

In 1952, the festival took place in the magnificent and inspiring Abbey of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa. Stern participated in the last five concerts, even joining the violin section of the small orchestra which Casals conducted in a cantata and a suite by Bach. It was the first time that Stern played a sonata in concert with Istomin (the Schumann Op. 105) and a trio with Istomin and Casals (the Brahms Third). It was a memorable experience which, unfortunately, would not be repeated soon. Schneider, discouraged by the shortcomings of the French Committee of Organization and the rampant jealousy between musicians who all wanted to monopolize Casals, resigned. Stern decided to give up too and never returned to Prades.

Stern did not meet Casals again until five years later, in 1957, at the Puerto Rico Festival. He was to play and record Schubert’s Trio in B flat major with Istomin and Casals, but due to heart problems, Casals had to cancel his participation in the festival. It was not until 1959 that the Trio Istomin-Stern-Casals was able to reunite for two concerts, where they gave wonderful performances of the first trios by Mendelssohn and Brahms. Unable to recruit Casals, Istomin and Stern chose to form a trio with Leonard Rose.

Istomin and Stern subsequently took part in the Puerto Rico Festival, sometimes with Casals or under his direction (notably for the Beethoven Triple Concerto with Leonard Rose in 1970). Both were part of the Music Committee of the Festival from the very beginning. They also joined Casals at the Israel Festival (1961, 1967 and 1973) and at the United Nations (in 1971).

After Casals’ death, Istomin and Stern joined forces on several occasions to pay tribute to him, particularly in Puerto Rico in 1975, and in Mexico the following year in a festival organized by Istomin. The most moving moment was in December 1976, when they played Casals’ unfinished Violin Sonata in Barcelona and then at Carnegie Hall to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth.

Isaac and Eugene

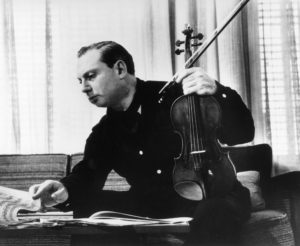

In his autobiography, Stern portrayed Istomin in these terms: “Eugene, slightly portly, as I was, was a superbly trained, deeply sensitive, learned and intuitive musician, as well as a voracious reader. When we played together, he never came to a rehearsal without being completely prepared. His analysis and knowledge of a score were always first-rate, and he’d bring to a performance not only musical insight but also a remarkably quick flexibility. He played the piano as if he were holding a bow. Musical phrases spun themselves from his fingers.” They gave very few full concerts in duet, but they quite often played sonatas in various chamber music programs, especially for the Beethoven bicentennial year. Their favorites were the Beethoven First and Tenth Sonatas, and the Brahms’ Sonata in G Major. Stern was so fond of Istomin’s playing that when Alexander Zakin, his accompanist for 37 years, was forced to end his career, Stern chose pianists who had studied with Istomin, like Jean-Bernard Pommier, Yefim Bronfman and Emanuel Ax, for his recordings and most important concerts

Stern had great esteem for Istomin’s musical instinct and culture. In 1973, he planned to do a series of interviews with Istomin for the Israeli Television. Only one was filmed. Stern questioned Istomin on his definition of music, his education, his career, the art of the piano… Here is a brief summary of Istomin’s answers.

Music distills emotion, which is the supreme objective of art, through sound and time. Music brings together most of the artistic disciplines: architecture, the art of color and line, dance (which plays a fundamental role) and poetry. It is the demonstration that humanity is in search of what can transcend it. The main qualities of a performer are eloquence, refinement, clarity. At the piano, he unconsciously tries to sound in turn like a flautist, a clarinetist, a string player. Intuition plays an essential role, but it is nothing without curiosity, the desire to learn and to know. Istomin talks about his education and his symbolic link with Beethoven, as a result of having been trained by Siloti, a former student of Liszt, who himself had met Beethoven! He mentions the pianists who impressed him and talks about his meeting with Casals. He advises young musicians not to be afraid of being influenced! He then plays the piano and sings (two arias from Don Giovanni!). Here is a link to watch some excerpts from this interview.

Istomin and Stern also shared the same political convictions. They both supported Israel, holding the same concept of a secular state. They had similar friendships with the great Israeli leaders of the Labour Party, from Golda Meir and David Ben-Gurion to Teddy Kolleck and Yitzhak Rabin. Istomin participated in the Mishkenot Sha’ananin project and its Music Center, and generously supported young Israeli musicians. Both had great difficulty going to Germany and Austria and performing there, while upholding their conviction that it was essential for Israel to rebuild ties with the former Nazi countries.

They both felt that the ascension of China was an essential event for the balance of the world. In 1971, Istomin tried in vain to obtain permission to perform and teach there. In 1979, Stern was invited, and the film of his tour had a tremendous impact. This symbolizes the huge difference in temperament and philosophy between the two men: Istomin never cared about his image and promotion, while Stern attached the greatest importance to it and had a genius for communication.

In American politics, they were faithful followers of the Democratic Party. Nevertheless, there was a difficult moment during the 1968 American presidential elections. Stern and Istomin were both very friendly with Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic candidate opposing the Republican candidate NIxon. The political situation in the midst of the Vietnamese crisis was very tense, and Humphrey needed backing from his supporters. Considering his notoriety, Stern should have led the Committee of Artists and Writers, but his wife Vera felt that in doing so there was more to be lost than to be gained for her husband’s image. Istomin was obliged to take over the leadership of the Committee. He did his best and stoically shouldered the blows, while Stern cautiously kept a certain distance.

Tensions and quarrels

Musically, there was no shortage of reasons for tension and quarrels!

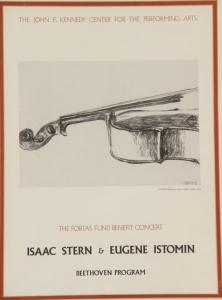

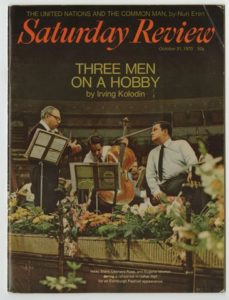

Stern had an annoying tendency of drawing attention to himself, frequently interrupting his colleagues and monopolizing the conversation during interviews and even in official events, such as the concert which the Trio gave at the White House. Although he often expressed great respect for his two partners in the Trio, and in particular for Istomin, he sometimes talked out of both sides of his mouth and paid too much attention to his entourage. Stern had a court of admirers everywhere, composed of music lovers and professionals, whom he knew how to cultivate and encourage. Some were particularly zealous and anxious to spotlight him. They would have liked the Trio Istomin-Stern-Rose to be called the Stern Trio. This designation appeared regularly in the programs or in the press, to the great anger of Istomin because his solo career was at stake. Just before the Beethoven series at Carnegie Hall in November 1970, Saturday Review devoted its cover and main article to the event. The planned title was The Stern Trio and was only replaced at the very last moment by Three Men on a Hobby, which prevented a major clash!

Fans of violinists or cellists always find that there is too much piano in sonatas and trios. Above all, they want to be able to hear their favorite instrument, regardless of whether it goes against the requirements of the music. They invariably complained to their idol about the pianist being too loud. The string player feels obliged to lend an ear to this recrimination while defending, more or less emphatically, his pianist partner. One time, at a concert in the Zurich Tonhalle, Istomin was given a dreadful piano, which was so loud that it was impossible for him to play piano. The critics mentioned the excessive presence of the piano and Stern’s admirers raised a huge fuss, finding it unacceptable that Istomin covered his partners. Stern, with Rose’s approval, reproached Istomin and insisted that he was tired of having to defend him all the time.

His speech outraged Thornton Trapp, the page turner and handyman of the Trio, who declared in his recorded diary: ‘’Stern said that he was tired of defending Eugene. His defense seems rather like handshaking with the right hand while backstabbing with the left. If Isaac truly believes that he is Eugene’s loyal defender, he ought not to be allowed at large. His endless upstaging, his toleration of injustices and criticisms and irritations suffered by Eugene, his refusal to stop the use of Stern Trio, his using Eugene because he couldn’t get a better teacher and partner are enough to drive anyone around the bend.“ Istomin’s reaction was as excessive as the accusation: he did not exceed a mezzo-forte for much of the next concert, which infuriated his partners. Ultimately, this question seems more a pretext for endless debate about the musical leadership of the piano in chamber music repertoire than a real problem in concerts and recordings. Trapp related that Stern, as well as Rose, regularly asked Istomin to play louder to support them when they were in charge of the melody. Otherwise, their sound might be not consistent enough and the thread of the musical phrase might be lost. In many interviews as well as in his autobiography, Stern praised Istomin for his remarkable sense of balancing the sound between the piano and strings.

There was a very difficult moment, which did not provoke a dispute but deeply wounded Istomin and Rose: the Concert of the Century at Carnegie Hall on May 18, 1976. Stern wanted to make a huge media splash. For this benefit concert which celebrated the 85th anniversary of Carnegie Hall, he invited Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, Vladimir Horowitz, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Mstislav Rostropovich, and even Yehudi Menuhin, whom he hated and with whom he had never played in concert. But he ignored his two old friends.

In fact, the greatest source of tension was what Stern modestly called in his autobiography, his ‘’relaxed attitude’’. He only mentioned his failure to warm up before going onstage, but there was also his devastating mania for being late, forgetting his scores, and arriving very poorly prepared at the rehearsals. Istomin was exasperated by this lack of respect both for him, who was always well prepared, and for the music! Stern, goaded on by Istomin, got down to things pretty quickly, but it sometimes needed one or two frustrating concerts before sparks flew and the performance reached its zenith. For the Kreutzer Sonata, it was even more difficult. Stern postponed the rehearsals and the first performance. Istomin pushed Stern so far that he exclaimed one day: “You’ll make a German fiddler of me yet !’’ Istomin could be very hard on Stern in rehearsals. Jaime Laredo heard him say: “You’re out of tune! It’s not what is written! You should practice!” Stern did not flinch, even if his self-esteem suffered, as he was aware that Istomin was pushing him to give his very best. The tension remained tangible at the concert, especially in the most dramatic sonatas, such as the Seventh and the Kreutzer. Alexander Schneider was at times amazed and amused himself by sending them a postcard of a painting by Goya called Riña a garrotazos (Duel with Cudgels). On the back of the reproduction, Schneider wrote: “Beethoven Sonatas, perfect coordination Isaac Stern-Eugene Istomin, painted especially for Columbia Records by Fr. Goya”.

The most serious crisis in their relationship was generated by Istomin’s decision to complete only the recording of the Beethoven Trios and to abandon the Sonatas for violin and cello. Columbia had refused to let him record at least one Beethoven concerto, which would have avoided confining his image to that of a chamber musician. Stern, just like Rose, understood Istomin’s anger and found Columbia’s attitude unfair, considering the enormous effort being asked of Istomin. However, they felt as if they were being held hostage in this conflict and that ultimately they had been betrayed by their colleague. Had it not been for the long series of concerts planned for the Beethoven year, and in particular the four complete chamber music series in London, Paris, Switzerland and New York, this could have led to the end of the Trio. The possibility that Istomin and Stern would resume recording the Beethoven Violin Sonatas together seemed more than improbable – but yet that is exactly what happened!

The recording of the Beethoven Sonatas

For many years, Isaac Stern toured and recorded only with Alexander Zakin. Despite this complicity, he did not often include Beethoven’s sonatas in his recital programs, with the exception of the Seventh (the only one he had recorded so far, in 1945). Stern thought that for these sonatas he needed a pianist with his own ideas, one who would involve him in a real dialogue. This was certainly the case with Istomin as, according to Thornton Trapp, their duo often resembled a duel!

In the early 1980s, ten years after the interruption, as the Trio’s career was coming to an end, Stern decided to give his recording activity a new direction. He wanted to record or re-record the entire chamber music repertoire apart from the trios. His first plan was to convince Istomin to complete the recording of the Beethoven Sonatas. Stern was very persuasive and, against all odds, Istomin accepted. Rejecting any contact with Columbia (now CBS), Istomin did not sign a contract, waived his royalties and delegated to Stern the responsibility of choosing the takes and following up on the editing. The two sonatas recorded in 1969 (the 1st and 7th ) were saved. They may give rise to a small regret that the recording was not completed at that time. There was an impetus and a natural sense of breathing which the sonatas recorded in 1982 and 1983 could not always recapture. Nevertheless, the whole series is fascinating, with some outstanding achievements, such as the 10th Sonata, which both loved so much.

In the early 1980s, ten years after the interruption, as the Trio’s career was coming to an end, Stern decided to give his recording activity a new direction. He wanted to record or re-record the entire chamber music repertoire apart from the trios. His first plan was to convince Istomin to complete the recording of the Beethoven Sonatas. Stern was very persuasive and, against all odds, Istomin accepted. Rejecting any contact with Columbia (now CBS), Istomin did not sign a contract, waived his royalties and delegated to Stern the responsibility of choosing the takes and following up on the editing. The two sonatas recorded in 1969 (the 1st and 7th ) were saved. They may give rise to a small regret that the recording was not completed at that time. There was an impetus and a natural sense of breathing which the sonatas recorded in 1982 and 1983 could not always recapture. Nevertheless, the whole series is fascinating, with some outstanding achievements, such as the 10th Sonata, which both loved so much.

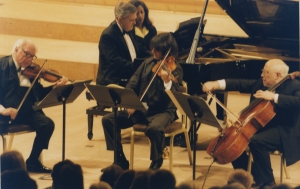

It was alongside Rostropovich that Isaac Stern and Eugene Istomin experienced their ultimate collaborations, at the Kennedy Center in 1987 for Slava’s 60th birthday, at the Evian Festival in 1990 and 1997, and in New York in November 2000 for a private party celebrating Istomin’s 75th birthday. In this ultimate event, Isaac wanted to host and perform, but health problems prevented him from doing so and he only attended and spoke briefly about the fifty years of musical complicity and friendship between them. Even more than a friendship, it was a brotherhood, an indestructible bond that made it possible to overcome any dispute and which outlived any storm.

Recordings and videos in studio

Beethoven. Complete Violin Sonatas. 1969 (Sonatas 1 and 7, New York, Columbia Studio) ; 1982 (Sonata 6, London, EMI Studio) ; 1983 (Sonatas 2, 3, 4, 5, 8, 9, 10, Washington, Library of Congress). Sony SM3K 64524

Beethoven, Violin Sonata in D major Op. 12 No. 1. Brahms, Violin Sonata No. 1 in G major Op. 78. Filmed in the BBC studios on July 29, 1973.

Some concerts

1950, June 19. Prades. Bach. Trio Sonata in G major BWV 1038, with John Wummer, flute. Recorded in the Prades studio by Columbia.

1952, June 21. Prades. Schumann, Violin Sonata No. 1 in A minor Op. 105. Brahms, Trio No. 3 in C minor Op. 101, with Pablo Casals.

1957, May 8. Puerto Rico. Mozart, Piano Quartet in E flat major K. 493, with Milton Katims, viola, and Mischa Schneider, cello. Recorded by Columbia.

1959, May 2. Puerto Rico. Mendelssohn, Trio No. 1 in D minor Op. 49. 8, with Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

1959, May 6. Puerto Rico. Brahms, Trio No. 1 in B major Op. 8, with Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

1963, August 8. Menton. Bach. Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major BWV 1050, with Jean-Pierre Rampal and the Northern Sinfonia conducted by Milton Katims.

1973, November 11. New York, Carnegie Hall. Brahms, Piano Quartet No. 2 in A major Op. 26, with Jaime Laredo, viola, and Leonard Rose, cello.

1975, June. Puerto Rico. Brahms, Violin Sonata No. 1 in G major Op. 78. Brahms, Piano Quartet No. 2 in A major Op. 26, with Pinchas Zukerman, viola, and Leonard Rose, cello. Recorded concert

1976, December 17. Barcelona, Palau de la Musica. Casals, Sonata for Violin and Piano (1st movement). Recorded concert.

1976, December 29. New York, Carnegie Hall. Casals, Sonata for Violin and Piano (1st movement). Recorded concert.

1978, January. Minnesota. Brahms, Violin Sonata No. 1 in G major Op. 78. (Funeral of Humphrey).

1980, April 17. Detroit. Brahms, Violin Sonata No. 1 in G major Op. 78. Brahms, Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor Op. 25, with Jaime Laredo and Paul Tortelier.

1987, March 27. Washington, Kennedy Center. Beethoven, Violin Sonata in D major Op. 12 No. 1. Concert for the 60th birthday of Rostropovich.

1990, May 22. Evian. Beethoven, Trio in B flat major Op. 97 “Archduke”, with Mstislav Rostropovich. Recorded concert.

1997, May 9. Evian. Beethoven, Violin Sonata in D major Op. 12 No. 1. Brahms, Piano Quartet No. 1 in G minor Op. 25, with Yuri Bashmet and Mstislav Rostropovich.

Documents

J.-S. Bach. Trio Sonata in G major BWV 1038. John Wummer, flute. Isaac Stern, violin. Eugene Istomin, piano. Recorded by Columbia in June 1950 at the Prades Festival. First ever concert and recording with Istomin and Stern playing together.

Audio Player.

Beethoven. Violin Sonata No. 1 in D major Op. 12 No. 1. Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern. Studio recording in 1973.

Audio Player.

Stern and Casals. Brief excerpt from Casals at 88, a documentary directed by David Oppenheim and produced by CBS in 1964. Casals welcomes Stern to Puerto Rico and talks about Bach.