Istomin devoted a section of his Great Conversations to chamber music. In a humorous and slightly provocative way, he entitled it The Virtuosos, affirming once again his double conviction. On the one hand, chamber music is as important a domain as symphonic music for most great composers, and sometimes even more important! On the other hand, it needs virtuosos in order to achieve its true dimension, and not “chamber musicians”.

Istomin had brought together a very prestigious panel: violinists Pamela Frank, Jaime Laredo and Arnold Steinhardt; cellists Lynn Harrell, Yo-Yo Ma and Sharon Robinson; pianists Claude Frank and Joseph Kalichstein.

This conversation is available on the Library of Congress website. The following is a summary, as accurate as possible, of what was said in the very friendly but intense conversations.

Eugene Istomin introduced the debate by mentioning one of his favorite works, the String Sextet in B flat major Op. 18 by Johannes Brahms.

Arnold Steinhardt: Perhaps the most fantastic musical experience I’ve ever had was playing this work with Casals in Puerto Rico, along with Sasha Schneider, Leslie Parnas, Michael Tree and Milton Thomas. We all had ideas, but Casals’ radiance was so impressive ! We were inspired by him – we could only follow his ideas!

Eugene Istomin: At the same time, you have to be able to give your very best and make yourself available to what is brought by tour partners, especially if there is an exceptional musician among them!

Pamela Frank: Chamber music is simply playing with other people. I like this interaction!

Sharon Robinson: You learn more from your colleagues than from your teachers! For the students it’s fantastic.

Claude Frank remembers playing Beethoven’s Sonata in A major Op. 69 with Leonard Rose. He told him that he did not like the way he played the first bars. Rose thought about it and replied: “I do!”

Joseph Kalichstein recounts his unique collaboration with Henryk Szeryng. He had not dared to say a word since the beginning of the rehearsal, but finally risked a suggestion about the Brahms Sonata in G major. There was a moment of silence, then Szeryng replied: “OK. Let’s try it!” After the try, there was another moment of silence, much shorter, before Szeryng exclaimed: “Dear Joseph, how wonderful! You made me play like I want!”

Eugene Istomin believes that the best interpretations are those where there is no need to say anything to each other. He readily admits that there had been many quarrels over egos within the Trio he formed with Stern and Rose, but he emphasizes that on stage they immersed themselves entirely in the music, listening to and respecting their partners, which is the very essence of chamber music.

Interpretation. Yo-Yo Ma asks this crucial question: “How does one make a work of music his own, if it is written by somebody else?!”

Eugene Istomin reminds us that the composer, even though he was generally the first performer of his works, was aware that his music could continue to exist only through performers, who would appropriate them! He refers to an essential precept of Socrates which states that all knowledge is reminiscence. This explains why we fall in love with a piece and become obsessed with playing it and making it our own. In fact, we “recognize” it. Istomin asserts that he has never played a work with which he did not feel consubstantial.

Claude Frank relates that once a composer friend asked him to play one of his works. Claude Frank offered to play it for him before the concert and receive his advice, but the composer absolutely refused. After the concert, the composer said to him: “Thank you so much! I really liked it, even if it was completely different from what I was expecting.’’

Arnold Steinhardt adds an anecdote which had been told to him by Robert Mann, the first violin of the Juilliard Quartet. They had prepared a Schönberg quartet and went especially to California to play it for the composer. Schonberg commented: “I never imagined my music could be played like this, but it is wonderful this way! “

Lynn Harrell talks about the somewhat disturbing feeling he occasionally has that a work is “his”. Eugene Istomin agrees, adding that when you own a work you love and when you play it the way you want, you are often tempted to think that you are the only one who plays it the way it should be played !

Joseph Kalichstein: We internalize the composer’s indications. We don’t play louder just because it’s marked on the score, but because we feel the inner necessity of doing so.

Claude Frank says that you can feel that you ‘own’ a work and still think that your performing is not good. This was the case with Mozart, who was often proud of his compositions, but almost never of the way he played them.

Eugene Istomin offers a list of the greatest violinists and cellists of the past and asks his guests which ones have influenced them the most.

Yo-Yo Ma: For the cello, Leonard Rose, my teacher, who has been incredibly patient and kind to me. He was very demanding while persuading me that I could achieve it. And Pablo Casals, who was and still is a permanent source of inspiration for me, especially for the greatest chamber music works. And I wish to add Emanuel Feuermann, whose recording of Schelomo by Ernest Bloch particularly impressed me.

Pamela Frank: Kreisler for the vocal quality of his playing, his warmth and humanity. I would have liked to know him personally. Heifetz, who changed the playing of the violin forever, and made life difficult for the violinists who succeeded him!

Lynn Harrell: My heroes and mentors have changed over time. There was Rostropovich, who brought a new way of playing the cello, very lyrical, very Slavic. Heifetz, although I never attended any of his concerts, but his videos have led me to profoundly change the way I played and worked. And Casals, whom I saw and heard for the first time in 1961 in Puerto Rico, when he played the Beethoven Triple Concerto with Serkin and Schneider. Casals’ physical and musical presence, his aura, have wowed me for a lifetime. I believe that it is very important to be confronted with such geniuses, who transport you, allow you to become aware of what music is all about.

Sharon Robinson: Casals, because I grew up with his records. Piatigorsky, of whom my teacher had been a student. Heifetz, who impressed me. And all the chamber music I had the chance to hear and do at home, with my family.

Arnold Steinhardt: There are three violinists to whom I return again and again for my pleasure and constant enrichment. Kreisler for the same reasons as Pamela Frank. Heifetz, whom I admire not only for his virtuosity but also the intensity of his playing, and who continues to fascinate me. Szigeti, with whom I worked and who still moves me. And, of course, Casals! All of them inspired me but they made my life difficult: what should I do after them?

Eugene Istomin reports that he once asked Heifetz which violinist he respected the most. His immediate answer was Kreisler.

Jaime Laredo: Heifetz, because he was doing things that I am not able to do, but that I can dream of getting close to! Casals, who remains the most important in my life, because he has profoundly changed my approach to music (I have his photo in my studio, and he is the one I question most often when I work). And Leonard Rose, who was my first chamber music teacher when I was 13 years old.

Joseph Kalichstein wants to add David Oistrakh and Isaac Stern to the names already mentioned, because he has listened to them so often. He also finds it much more comfortable to be inspired by musicians who do not play the same instrument!

Claude Frank: Casals and Szigeti. He does not think of them as instrumentalists but rather as musicians, as their influence goes far beyond their instrument!

Eugene Istomin talks about the viola and the great violists, especially William Primrose. Jaime Laredo plays the viola and the work he prefers to perform, out of all the repertoire, is Harold in Italy. Arnold Steinhardt also plays it sometimes. They all emphasize the essential role of the viola in chamber music, and the fact that many composers were violists, in particular Dvořák.

How has musical life changed over your lifetime?

Jaime Laredo: Today, it has become impossible for me to recognize the sound of violinists. Previously, when listening to the radio or a record, I only needed three bars to know who was playing!

Arnold Steinhardt notes that young people are no longer searching by themselves but instead, make up an impersonal synthesis of what is being done. Sometimes his students ask him: ‘How should we play Mozart?’ They think there’s only one way, while there are many other ways that can be valid! They are not trying to exist as individuals and are not willing to question themselves throughout their lives. Before, there were various influences and fashions, but everyone was researching!

Eugene Istomin presents the program of a recital given by Nathan Milstein at the Library of Congress in 1946: Vitali, Chaconne; Bach, Sonata for Solo Violin in G minor BWV 1001; Milstein, Paganiniana; Mendelssohn, Concerto; and, as encores, Chopin, Nocturne Op. 9 No. 2 and Wieniawski, Scherzo-Tarantelle. He asks if such a program would be conceivable today.

Arnold Steinhardt: Today, ”lollipops” are no longer appreciated by listeners and young violinists don’t know what to do with them. We live in a different time.

Joseph Kalichstein deplores the fact that classical music audiences are now standardized and sanitized. It would be nice if the public could regain some innocence and freedom. He gives the example of his own children, who don’t ask themselves such questions when listening to pop music: they like what they like, and that’s it!

Arnold Steinhardt: You have to enjoy yourself, whatever you play, even if it is the Bach Sonatas and Partitas! These days, young musicians do not have the desire or the will to find their own way. Above all, they don’t want to do anything tasteless.

Jaime Laredo: The level is incredibly high among students, but they are too anxious to play correctly, to be “good” musicians.

Lynn Harrell: They fear being criticized if they don’t do what others do. Yes, there is strong competition, but in the past that didn’t prevent you from looking for your own way.

Joseph Kalichstein observes that today’s competition encourages young people to play like everyone else, just a little faster, like in sport, and above all, to play as consensually as possible. He also regrets that we can no longer recognize the sound of a pianist, whereas in the past we could. He only needed three notes to recognize Rubinstein.

Yo Yo Ma wonders what has caused this change of mentality.

Pamela Frank suggests that it may be due to the teaching. Given the very high general level, it seems logical that there are fewer personalities. Young people want to make the safest choices, because in competitions originality is often not well received.

How to enable young people to develop their own personalities

Lynn Harrell is concerned about the development of today’s young musicians. There are those who take the opposite view of everything and those who are too conformist. The problem is that they need time to mature and today’s careers do not allow for this.

Claude Frank: We regret the lack of personality of young musicians, but we immediately compare them to the greatest. That’s not fair!

Eugene Istomin underlines the responsibility of the managers and the music community. We take young people and push them towards success and money. Then they are thrown away and replaced by others of the next generation. Art in general has never been so close to business. Young people are not aware of the danger – they are driven by people and by the system, by success! We can’t blame them for that. But they don’t realize that they are forgetting the essential. We must not overlook all the sacrifices that are required of talented young people. They don’t have a normal life, and they have no guarantee of success! .

Eugene Istomin underlines the responsibility of the managers and the music community. We take young people and push them towards success and money. Then they are thrown away and replaced by others of the next generation. Art in general has never been so close to business. Young people are not aware of the danger – they are driven by people and by the system, by success! We can’t blame them for that. But they don’t realize that they are forgetting the essential. We must not overlook all the sacrifices that are required of talented young people. They don’t have a normal life, and they have no guarantee of success! .

Arnold Steinhardt tells an anecdote about Anton Rubinstein, who reportedly told Joseph Hofmann, who at one time was studying with him, that he would never play for him because he didn’t want him to copy, or try to copy him. Today’s students should be told: Your studio is a laboratory – do whatever you want in it, no matter how “tasteless” it may be.

Pamela Frank recalls that her teacher, Szymon Goldberg, practically forbade her to give concerts when she was studying: “Now you study, later on you will have plenty of time to give concerts.” And she agrees with this principle.

Eugene Istomin remembers Zukerman’s audition in 1961. The young violinist was 13 years old at the time and he played for Casals, who said: “Let him go on stage. Let him play and grow.” It was as simple as that. Casals thought talent would develop naturally.

Eugene Istomin remembers Zukerman’s audition in 1961. The young violinist was 13 years old at the time and he played for Casals, who said: “Let him go on stage. Let him play and grow.” It was as simple as that. Casals thought talent would develop naturally.

Jaime Laredo wants his students to play concerts as often as possible, even if they are not really ready.

Yo-Yo Ma believes that the most important thing is to dream. Of course, it is essential to work hard, but dreaming is crucial for the development of personality.

.

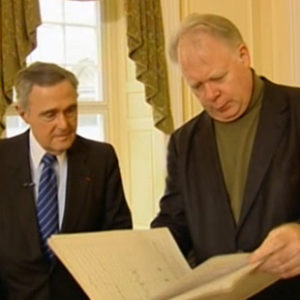

In the version of this Great Conversation which was formerly available on DVD, there were also about ten minutes during which Eugene Istomin introduced his colleagues and friends to some of the most precious manuscripts in the Library of Congress.

He began with Mozart’s Violin Concerto K. 219.

Pamela Frank remembers the first time she heard this concerto. She was overwhelmed by the entry of the violin after the initial tutti. A miracle! She continues to be amazed by the tempo indication which Mozart wrote: Allegro aperto! She points out that many of Mozart’s works fall within this notion of “open” tempo, but Mozart used this adjective only very rarely (the Oboe Concerto K. 314 and the Piano Concerto K. 238…).

.

Arnold Steinhardt says that he performed this concerto when he was 21 years old. George Szell was in the audience and told him after the concert: “Young man, you are very gifted, but you don’t know anything about ornamentation in Mozart’s music.” Szell suggested that he go to the Library of Congress and look at the manuscript, which would teach him everything he needed to play Mozart on the violin. So this is the second time he is facing this manuscript and he is deeply moved. He adds that it is certainly important to be respectful of what is written, but we must not limit ourselves to this alone. Depending on his mood of the day, Mozart might have scored his music differently, and he would probably not have been opposed to future performers taking a few liberties. We have to be creative and imaginative.

Lynn Harrell thinks that the miracle Pamela Frank is talking about is that for the first time the violin appears as an opera singer.

Eugene Istomin then presents the score of Schelomo by Ernest Bloch.

Yo-Yo Ma is amazed by the beauty of the manuscript and its immaculate appearance, as if it were the work of a copyist. Not a single erasure! Lynn Harrell is very moved to see the manuscript of what he considers to be one of the greatest masterpieces of the cello repertoire.

Yo-Yo Ma and Claude Frank discuss Mozart’s manuscripts, which normally have no deletions, apart from some exceptions, notably the Piano Concerto in C minor K. 491.

Yo-Yo Ma wonders whether Beethoven ever wrote a manuscript without deletions. Never, replies Eugene Istomin, specifying that sometimes Beethoven could be so excited that he did not take the time to put notes on the stave but only wrote their names on it.

Jaime Laredo makes fun of musicologists who look in Beethoven’s manuscripts for the exact place in which to begin a crescendo or place an accent… Impossible!

A discussion begins on the evolution of scores: in the past, manuscripts were so imprecise and incomplete, sometimes barely legible; today, computers give them a scientific precision!

Eugene Istomin now shows the manuscript of the Chausson Poème, and everyone is thrilled by its beauty and clarity.

At this point, Claude Frank wants to talk about another manuscript which is on the table, the Sonata for Piano and Violin in G major (K. 379). Mozart, exceptionally, had made some deletions in the variations of the second movement. Claude Frank goes to the piano, and Istomin asks him to first play the beginning of the work, with the piano entering on its own, to show how these Mozart sonatas are not violin sonatas, but actually sonatas for piano and violin! Claude Frank plays the beginning and then the theme of the second movement and the sublime variation which is accompanied by the pizzicati of the violin. Everyone is ecstatic.

.

In the DVD version, there are also a few brief moments that are omitted in the downloadable one.

Eugene Istomin asks his guests about the essence of chamber music.

Claude Frank expresses his love for it and enjoys telling an anecdote about Rudolf Serkin, of whom a journalist once asked this question: “What do you think of chamber music?” Serkin, stunned, asked him to repeat the question, and replied by saying: “I don’t know what that is, I only know music!’’

Claude Frank expresses his love for it and enjoys telling an anecdote about Rudolf Serkin, of whom a journalist once asked this question: “What do you think of chamber music?” Serkin, stunned, asked him to repeat the question, and replied by saying: “I don’t know what that is, I only know music!’’

Joseph Kalichstein emphasizes the educational value of chamber music. We learn to listen to ourselves and to others.

Pamela Frank finds chamber music to be a beautiful way to compensate for the loneliness of being a soloist. She loves this interaction with other musicians. By making chamber music, she made friends with many musicians, without even having to speak first. That’s also how she met her husband! When you make chamber music, you are in direct contact with the souls of your partners.

At the end, Eugene Istomin warmly thanks his guests, believing that their participation makes this film an invaluable document for future generations. .

Documents

The video of this Great Conversation in Music entitled The Virtuosos can be downloaded at https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200031105/

Here are a few other documents featuring most of the participants in this exceptional conversation.

40th Anniversary Scrapbook of the of the Trio Kalichstein-Laredo-Robinson

.

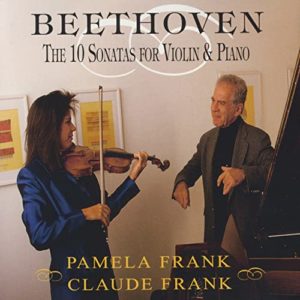

The Duo Pamela and Claude Frank. Schubert. Violin Sonata in A Major D. 574, first movement. (Sound only. CD Arte Nova)

.

Bloch. Schelomo – Hebraic Rhapsody for Cello and Orchestra. A work which Lynn Harrell considers to be one of the greatest masterpieces of the entire cello repertoire. For this recording, he is accompanied by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Bernard Haitink. (Sound only, CD Decca)

.

.

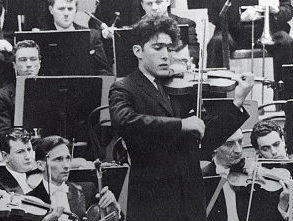

As mentioned in this conversation, the Brahms Sextet in B flat major Op. 18 was one of Istomin’s favorite works. It was also with this work that Arnold Steinhardt had his “most fantastic musical experience”, when he performed it with Casals in Puerto Rico. This was on May 27, 1964. Here are a few images of the last movement, where we can see Arnold Steinhardt and Alexander Schneider, violins, Milton Thomas and Michael Tree, violas, Pablo Casals and Leslie Parnas, cellos.