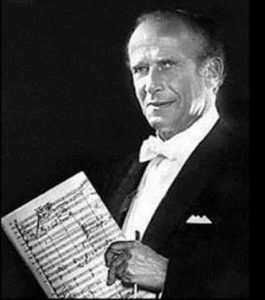

Milton Katims died in 2006 at 96, after a very rich life and career. He was one of the most distinguished violists of the 20th century. In 1943, he succeeded William Primrose as the NBC Orchestra’s principal viola for Toscanini, who encouraged him to conduct, and subsequently made him his assistant. For fifteen years, Katims was the favorite partner of the Budapest Quartet, recording quintets by Mozart, Beethoven and Dvořák. He was also a member of the New York Piano Quartet along with Mieczyslaw Horszowski, Alexander Schneider and Frank Miller.

In 1954, Katims was appointed musical director of the Seattle Symphony. He stayed for twenty-two years and considerably developed the orchestra, not only in regard to its artistic level but also creating a more numerous and sophisticated public. Istomin was frequently invited to perform under his baton or to take part in the famous chamber music series which Katims had founded at the Olympic Hotel. In 1962, Istomin appeared at the Seattle World Fair, both as soloist and chamber musician. Katims and Istomin also collaborated at the Prades and Puerto Rico festivals together with Casals, and at the Menton Festival in 1963, where Princess Grace of Monaco attended their concerts.

Funny moment at Prades in 1952: Isaac Stern, Maud Tortelier, Leopold Mannes, Madeline Foley, Milton Katims, Paul Tortelier

In The Pleasure Was Ours, the book he wrote together with his wife Virginia, Milton Katims tells a delightful anecdote, which was a continuation of the pleasant days they had spent together during the Prades Festival. Katims graciously allowed Istomin the privilege of relating the following incident: “One of the most amusing moments in my career came at a time in 1952, when I connived with members of the Buffalo Philharmonic to play a prank on our conductor, a certain Milton Katims, during a performance of the Chopin Second Piano Concerto. We had performed the work at subscription concerts in Kleinhans Hall in Buffalo and were now on a short runout tour with the same program. It was quite the conventional habit to make a cut in the opening orchestral tutti, so that the solo piano’s dramatic and glamorous entrance would not be delayed too long.

Many recordings of this beautiful work by artists like Arthur Rubinstein, Guiomar Novaes, and even myself, with Eugene Ormandy, were made with the cut. But for the Buffalo performances we were not making the usual cut, because Milton felt there was already too little for the orchestra to play. At the final concert on the tour (at Colgate University in Hamilton, NY), I conspired with the players to make the cut without telling maestro Katims. At the performance, the spectacle of Milton’s horrified expression of stunned surprise – head nodding back and forth as if he were denying the reality of what we have done, while he tried to catch up with the score, was a choice moment, yet one of which I am not at all proud, since I was no longer a twelve-year-old schoolboy at the time. However, apart from having to reimburse Milton for his cardiologist’s bill, no serious damage was done by the incident”.

At this point, Katims took over to tell his side of the story and recount his revenge… “I found myself quite confused. I had just turned to cue the first violins, but they didn’t play! The woodwinds played instead. Out of the corner of my eye, I saw Eugene peering up at me in a very peculiar manner. (…) Although I was momentarily upset by Eugene’s prank, I said very little about it. I waited patiently for the right moment to return the favor. It came about ten years later when Eugene came to Seattle to play the Schumann Piano Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. The concerto is in A minor. I had our librarian put out the parts for both the Schumann and the Grieg Piano Concerto, which are in the same key. At the first rehearsal, after Eugene played the opening of the Schumann, I conducted the orchestra in the opening of the Grieg. He may have been laughing or crying inside, but Eugene didn’t bat an eye. He shook his head and said with a wry grin, ‘Very funny. Very funny’.”

Katims and Istomin were among the small group of outstanding New York musicians who, in the late 40s and early 50s, gathered for the pleasure of playing chamber music together. Their friendship and mutual esteem dates from this time. These feelings are evident in Milton Katims’ book as he recalls Istomin: “I would venture to say that his name is much better known among his fellow artists than by the general public. The reason is that he is a musician’s pianist. His powerful virtuosity, tempered by a rare poetic intellect and style, has brought him triple acclaim – as a recitalist, a chamber musician, and a soloist with the world’s greatest orchestras and conductors.“

Katims and Istomin were among the small group of outstanding New York musicians who, in the late 40s and early 50s, gathered for the pleasure of playing chamber music together. Their friendship and mutual esteem dates from this time. These feelings are evident in Milton Katims’ book as he recalls Istomin: “I would venture to say that his name is much better known among his fellow artists than by the general public. The reason is that he is a musician’s pianist. His powerful virtuosity, tempered by a rare poetic intellect and style, has brought him triple acclaim – as a recitalist, a chamber musician, and a soloist with the world’s greatest orchestras and conductors.“

Concerts

1952, December 14 & 16. Buffalo. Chopin, Concerto No. 2. Buffalo Philharmonic.

1954. Seattle, Orpheum. Beethoven, Concerto No. 5. Seattle Symphony.

1957, May 2. Puerto Rico. Mozart, Piano Quartet in E flat K. 493. Isaac Stern, violin; Mischa Schneider, cello. Concert recorded and issued by Columbia.

1962, May 19. Seattle. Brahms, Piano Quartet in G minor Op. 25. Isaac Stern, violin; Leonard Rose, cello.

1962, May 21. Seattle. Mozart, Concerto No. 24 in C minor K. 491. Seattle Symphony.

1963, August 8. Menton. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major BWV 1050. Northern Sinfonia. Isaac Stern, violin; Jean-Pierre Rampal, flute.

1964, July 28. Hollywood Bowl. Beethoven, Concerto No. 4. Los Angeles Philharmonic.

No information available for other concerts with the Seattle Symphony or in the Olympic Hotel series.

Music

Mozart, Quartet for Piano and Strings in E flat major K. 493, last movement. Eugene Istomin, piano. Isaac Stern, violin. Milton Katims, viola. Mischa Schneider, cello. Live recording at the Casals Festival in Puerto Rico on May 8, 1957 (Columbia).