Istomin was attracted by paintings very early on, even if he was never tempted, like his friend Kapell, to paint or draw himself. Lisa Mangor, a friend of his mother’s from the Russian immigrant community, was a figurative painter who was quite often exhibited in New York galleries in the 1940s and 1950s. She initiated him into the world of art by taking him to galleries and museums, and contributed to his idea of collecting. He bought several of her paintings (The Dancer, Bouquet of Flowers, Bright Colors in Yellow Vase and Bouquet of Flowers in a Green Vase) which he kept all his life. It was on her advice that he acquired his first major work – a drawing by Paul Klee entitled Heroic Fiddling.

In the autumn of 1945, Adolf’s wife Frieda Busch, who had a very maternal affection for Istomin, put him in contact with Justin and Kate Tannhauser. These great gallerists and art dealers had immigrated to the United States. Justin Tannhauser immediately developed a great deal of sympathy for this young pianist who was so open to all the arts. He helped him to deepen his artistic education, welcoming him into his home and showing him his exceptional personal collection, much of which he was to bequeath to the Guggenheim Museum in 1963, and gave him an etching of Picasso. Istomin had fallen in love with a Picasso gouache, for which Tannhauser offered him a very favorable price and payment in several installments. Istomin had to resell his Klee drawing and had great difficulty fulfilling his financial commitment, for which Tannhauser kindly agreed to postpone the deadline.

This first purchase was characteristic of Istomin’s attitude – when he loved a piece of work, he bought it if he could! It was that simple. The notion of speculation (buying because it will increase in value) was absolutely foreign to him. At times he would become carried away and engage in reckless bouts of spending, paying an excessive price for a work of art which had captivated him.

His collection contained relatively few classical and romantic works. His most significant pieces were a small Rembrandt etching dated 1637 (Three Heads of Women, One Asleep), a Charles Turner watercolor dated 1847 (Brighton Bridge) which had been offered to him by the Busch family, and a pencil drawing by Eugène Delacroix (Figure Studies). He also had a portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven sketched by Edward Burne-Jones. . .

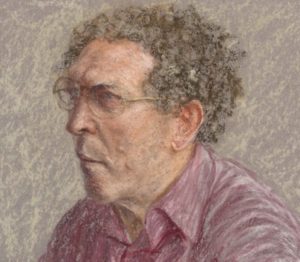

Istomin was much more interested in contemporary art. He appreciated being in contact with the artists, especially with Avigdor Arikha, who was one of his closest friends for nearly forty years. Arikha, who admitted that Istomin had a “good eye”, helped to refine it and to broaden his culture through gallery visits and long discussions. He sometimes advised him on his acquisitions. Istomin owned nearly forty works by Arikha, some paintings from his abstract period, two watercolors and above all, drawings (portraits of Istomin, Anna Arikha, Casals, Marta, Beckett, Jean-Bernard Pommier, self-portraits, still lifes, and landscapes). He purchased some of them, but most of the drawings of Istomin at the piano were gifts from the artist. . . .

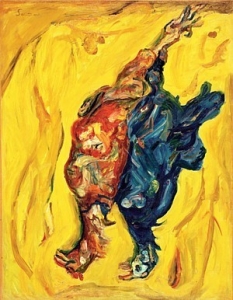

In 1946, Istomin met Norris Embry during his summer stay at Martha’s Vineyard with Shirley Gabis. He was attracted by the brilliant intelligence and vast culture, especially literary, of the young painter. They were both admirers of Ezra Pound and engaged in intense philosophical and religious discussions. Shortly afterwards, Norris Embry, who was already prone to fits of schizophrenia, left to discover Europe in his search for inspiration. In the summer of 1948, Embry was in Florence with his chosen master, Oskar Kokoschka. When Istomin came to visit the city, Embry was a wonderful guide. Subsequently, relations became more distant as Embry led an endless wandering life and had to be hospitalized. In the early 1960s, Istomin bought four paintings from him: Horse, oil on paper and watercolor; Abstract Composition – 1962, oil on paper; Figures-Women 1959; and Actor, an undated gouache.

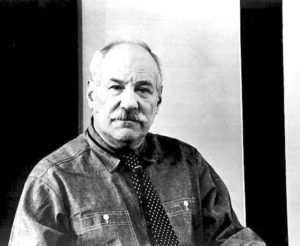

Eugene Istomin was also friendly with another abstract expressionist painter, Barnett Newman (1905-1970), whose modernism was even more radical. Newman had to wait until the very end of his life before finally being recognized as a great artist and seeing his market value reach vertiginous heights, after having lived in poverty until the age of sixty. Istomin loved the artist less than he did the man (he only acquired one lithograph). Like his wife, Newman was passionate about music and had played the piano in his youth. He was an idealist who refused to compromise and who fought against injustices, whatever they might be. Having taught for a long time in schools (without ever having gained tenure!), he advocated the development of education and the importance of art and artists in society. Istomin shared these convictions and admired his immense artistic and literary culture (Newman had been invited to Paris in 1968 to give a lecture on Baudelaire!). When Istomin was working on Schubert’s great Sonata in D major and was still hesitant about performing it in public, he felt the urge to try it out on an audience of friends chosen for their musical sensitivity. He played it for Barnett Newman and his wife, and their enthusiastic reaction helped him to decide to include it in his recital programs.

Istomin was also connected with Richard Diebenkorn, a painter who had followed a path which was the exact opposite to that of Arikha, at about the same time. in his early days, Diebenkorn was one of the most outstanding representatives of the abstract Expressionist school, which was then very popular on the West Coast. A great admirer of Hopper, he returned to figurative art in the mid-1950s, with equal success. Later, the discovery of some of Matisse’s great paintings, in particular Fenêtre à Collioure, led him to return to abstraction in 1966. This time it was a lyrical abstraction far removed from the expressionist abstraction of his beginnings. Diebenkorn embarked on a series entitled Ocean Park, some 140 paintings and several hundred works on paper which were executed over a period of 20 years. Istomin was fascinated by his complex progression and continual questioning, and by his determination to achieve the ultimate limits of his ideas. In 1977 and 1982, he bought two works, including one from the Ocean Park series (charcoal and gouache). Diebenkorn also gave him two etchings. In an attempt to learn more and understand everything about the painter’s approach, he built up a collection of no less than thirteen exhibition catalogues (between 1980 and 2000) and five books. Diebenkorn had kindly autographed Eugene and Marta Istomin’s edition of the Richard Newlin book entitled Richard Diebenkorn: Works on Paper, as well as the large poster announcing an exhibition of his paintings on the occasion of the Kennedy Center’s tenth anniversary.

In 1961, during his participation in the first Israel Festival, Istomin met Joseph Zaritsky, a painter born in Ukraine in 1891 who had emigrated to Palestine by 1923. He followed closely the evolution of his work, which was inspired by the landscapes of Israel, and to which Zaritsky gave an increasingly abstract vision over the years. In 1964, he received a watercolor by Zaritsky in recognition of his participation in the previous year’s Israel Festival. In 1970, he bought a large-format oil painting from Zaritsky which he brought back to America by plane along with his luggage – not an easy feat! He also possessed one lithograph and a watercolor which Zaritsky had dedicated to him.

To be exhaustive on the place of contemporary art in Eugene Istomin’s collection, other works would have to be mentioned: a drawing by David Hockney (Portrait of J.B. Priestley); a watercolor by John Anderson; a drawing by Leonor Fini (Le réveil); a study by Irving Petlin for The Restless Men; and an ink drawing by Jane Wilson entitled Eugene’s Chair, which was a gift from the artist.

However, the works that Istomin most cherished belonged to the first half of the 20th century. The best represented artist was Pablo Picasso with seven items: a 1959 gouache, Scène de corrida; a watercolor, Femme au bras levé; a study for the famous painting Trois femmes – 1908, which had belonged to Apollinaire; two etchings (La Danse – 1905; Les Pauvres – 1905 from the Saltimbanques suite edited by Ambroise Vollard); a lithograph of 1924, Femme assise; and a charcoal and pencil study for Three Guitars. Picasso was also by far the most present artist in Istomin’s library, with eighty-nine books, including some priceless collections of original lithographs. .

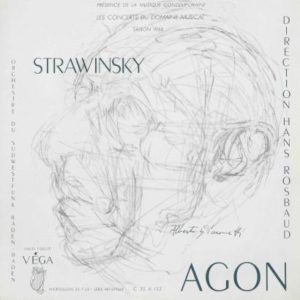

Matisse and Giacometti were almost as important as Picasso in Istomin’s artistic pantheon. He had acquired two important drawings by Matisse, Jeune Femme (femme assise) and a study for Tabac Royal. He also acquired some twenty-three books to explore the whole of Matisse’s work. As for his two drawings by Giacometti (Interior in Stampa 1955 and Portrait of Igor Stravinsky 1957), they were among the works he most treasured. He found it very moving that Stravinsky, who had been able to see the Giacometti exhibition presented by the Guggenheim Museum in 1955, wanted to meet Giacometti in Paris two years later. Stravinsky had come for the premiere of his ballet Agon at the Paris Opera. He agreed to pose for Giacometti, who made about twenty drawings, in very different attitudes and perspectives. Istomin would have loved to attend these sessions, which brought together two of the artists he admired most! One of the sketches was used for the cover of Agon‘s first recording. .

The rest of his collection included isolated works that had caught him during his visits to galleries around the world. There were lithographs by Maillol (Female Nude Seen from the Back), Braque (La Théière – The Teapot), André Masson (Portrait 1938), Renoir (L’enfant au biscuit), Joan Miro and Jacques Villon. Istomin was very fond of three pencil drawings: Musicienne by Cocteau (dedicated to Carole Weisweler), Le Jour by Juan Gris (still life with bottle, glass, plate and newspaper), and Les Instruments de musique by Fernand Léger (dated 1925). And to complete the inventory of the nearly one hundred works in his collection, there remains a Soutine canvas painted in 1919, Brace of Pheasants, and a unique sculpture, a bronze by Jacques Lipchitz (Figure, 1915).

Istomin’s library was exceptionally rich in art books – he had nearly two thousand which covered the entire history of art, from Greek antiquity to the contemporary period. The painters of his collection occupied an important place, but there were also books on important artists of all periods as well as numerous aesthetic essays (the complete writings on art by André Malraux, signed by the author).

Istomin needed the physical presence of his paintings, and since his financial means did not allow him to acquire very expensive works, his library served as a museum. For a long time, his travels allowed him to discover museums all over the world, particularly in Paris, London and Italy. However, as the years went by, he found it increasingly difficult to tolerate the crowds. He would arrive early in the morning and leave as soon as there were too many people, regardless of the interest of the museum or exhibition. He eventually gave up going to museums, making only rare exceptions when accompanying Marta to see certain paintings.

In addition to the fine arts, Eugene Istomin was also passionate about Greek and Chinese civilizations and had acquired many books, some vases and other objects of art.