The 1950s had been a steady ascent for Istomin, leading him into the antechamber of the firmament of great piano stars. The 1960s, although rich in adventure and success, did not allow him to enter. Two events contributed towards preventing him from doing so and would gradually tarnish his image and solo career: the clash with Columbia and the founding of the Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio.

Before leaving Columbia, David Oppenheim had completed the artists’ planning until 1961, when Istomin was scheduled to re-record Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto in stereo. Dissatisfied with the way his recording of the Tchaikovsky Concerto had been promoted, Istomin asked for a meeting with Goddard Lieberson, the president of Columbia. A lunch was organized, which was also attended by Schuyler Chapin, the new head of “Artists and Repertoire”. In the past, Chapin had been quite friendly with Istomin, but he held a grudge against him for not having obtained the position of manager of the Philadelphia Orchestra. He wrongly thought that Istomin had not supported his cause with Ormandy. During this lunch, the discussion was tense and led to the cancellation of the planned recordings.

Until Chapin’s departure at the end of 1963, Istomin did not record a single disc. After Chapin left, Istomin returned to the Columbia studios, but mainly because of the Trio. Between 1965 and 1970, he recorded fourteen works with Stern and Rose, but only two concertos (the Brahms Second and Beethoven Fourth) and one solo piano disc (Schubert’s Sonata in D major). The relationship of mutual trust had been shattered. Istomin felt that Columbia kept him on only for the Trio, and that he was occasionally granted a solo recording to prevent him from getting angry and signing with another company. Columbia reproached him for his high demands. Istomin was rarely satisfied with his recordings. He was reluctant to resort to editing and was always looking for the perfect take, asking for a greater number of sessions. He recorded Beethoven’s Waldstein Sonata twice, without giving permission to issue either one. Nevertheless, the 1959 version, recently published by Sony, was fantastic. Despite these tensions and mutual distrust, the collaboration between Istomin and Columbia continued until 1970.

The clash with Columbia had no immediate impact on Istomin’s engagements. During the 1960-61 season, he performed with twelve American orchestras: Boston (Munch and Monteux), Chicago (Reiner), Philadelphia (Ormandy), San Francisco (Kirchner), Los Angeles (Basil), Detroit (Torkanowsky), National Symphony (Mitchell), Milwaukee, Seattle, Rochester, Rhode Island and New Britain. Some successes were particularly spectacular or rewarding. Claudia Cassidy, his sworn enemy in the Chicago Tribune, surrendered after a performance of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto under Fritz Reiner, which she qualified as “a most beautiful performance”. After another Emperor Concerto, at the Hollywood Bowl with Ormandy, the audience applauded him endlessly, long after the stage lights had been turned off.

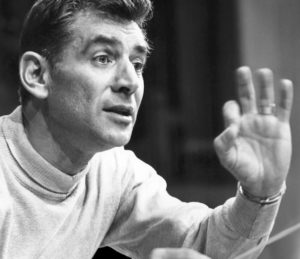

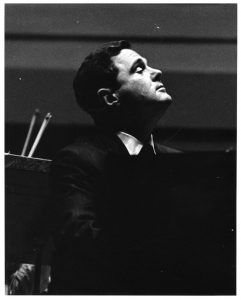

In 1962, Istomin took part in the two biggest events of the year. At the Seattle World Fair, he played a Mozart concerto with the Seattle Symphony conducted by Milton Katims and a chamber music concert with Stern and Rose. For the highly-anticipated inauguration of the Lincoln Center in New York, he was one of the soloists for the very first concert in late September (Concerto for 4 keyboards by Bach), and subsequently performed Brahms’ Second Concerto four times under Bernstein in October.

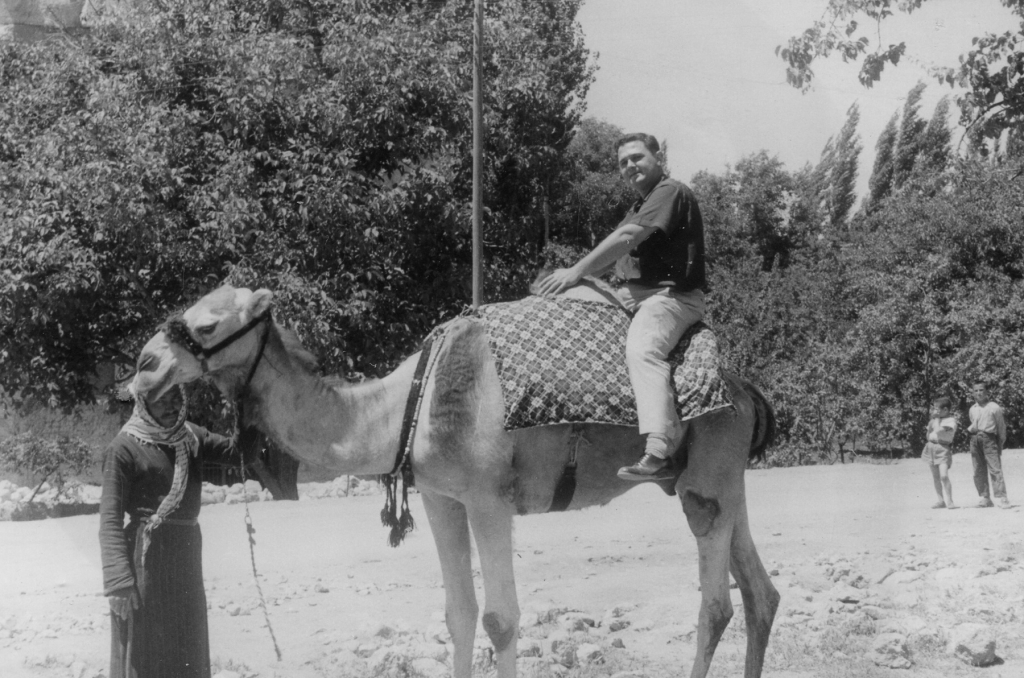

1963 was dedicated to the rest of the world. For more than six months, he did not spend a single day at home. From mid-April, he had placed himself at the disposal of the State Department and gave a long series of concerts in Bulgaria, Turkey, Iran and Afghanistan.

Eugene Istomin the great traveller on a camel’s back!

At the end of May, he went to Israel to play nine times with the Israel Philharmonic and to give several recitals. He made a brief stopover in Lebanon and spent a few days in Paris where he was to rehearse with Stern and Rose. His summer was an uninterrupted succession of festivals, with more than forty concerts in two and a half months (Aix-en-Provence, Menton for four concerts, Lucerne for three concerts, Montreux for two, Edinburgh for three, Stresa, Florence, Israel…). He continued with the opening of the new season in London (with, in addition, a recording for the BBC), Copenhagen, Stockholm, Geneva, Milan, Brussels, Antwerp… When journalists asked him about this frenzy of travel and concerts, he replied: “My home is everywhere there is a piano”.

These seasons seem to be copied and pasted from the frenetic seasons of the 1950s, but with one essential difference: the place of the Trio. Istomin, Stern and Rose had decided to launch the Trio for good, six years after their first experience at the Ravinia Festival. The three friends constructed a well-planned strategy: numerous rehearsals in 1960 and early 1961; debut concerts in Israel and England in the autumn of 1961; conquest of the United States in the spring of 1962 and Europe in 1963; first recordings in 1964 (Schubert 1, Brahms 2, Beethoven Triple Concerto). .

The activities of the Trio occupied a significant place in the agenda: between two to three months from 1961 until 63 (with solo concerts in between); nearly two months from 1964 until 69; and six months in 1970, for the Beethoven year. This disrupted Istomin’s schedule and meant that some projects had to be abandoned. What was even more disturbing was that the Trio monopolized the media’s interest. A Trio which brings together three great soloists is an exceptional event which appeals to everybody. The public and critics unconsciously assumed that this was the core of Istomin’s activity, at the expense of his reputation as a soloist. Another consequence of the founding of the Trio was that Istomin decided to change his management. In 1962, at Stern’s request, he left Columbia Artists and joined him at Hurok, to simplify the management of the Trio’s engagements (Rose did the same a few years later). If he was not very happy at Columbia Artists, he felt even more uncomfortable at Hurok.

Another important development in Istomin’s career and life was his growing political involvement. He was convinced, like Casals, that an artist is first and foremost a man responsible for his actions and words. This impacted the geography of his concerts. Germany and Austria were excluded because the Nazi period was still too fresh a memory, as were Spain (because of Franco) and Greece (after the military coup of the colonels). From the moment he participated in the first Israel Festival in September 1961, he became aware of the importance of playing regularly and supporting the Israeli state, so often under attack. Above all, he decided to serve his country, believing that culture, and in particular music, were now diplomatic weapons of utmost importance. He found that the Soviet Union used them with great skill, while the American governments neglected them. By 1956, he had accepted tours in Iceland and the Far East under the aegis of the State Department. He never ceased his efforts to motivate the Kennedy and Johnson administrations into developing an ambitious international cultural policy, declaring himself available for any mission and not asking for any fee. In 1963, he was sent to Bulgaria, an adventure worthy of the Cold War spy novels, and then to the Middle East. In 1965, he spent four weeks in the USSR, recently taken over by Brezhnev, followed by two weeks in Romania. The following year, he went to Saigon, where the situation was so unstable that he was not allowed to play.

Istomin also became involved in US domestic politics, strongly supporting the Democrat candidates, Kennedy against Nixon in 1960 and Johnson against Goldwater in 1964. He even proclaimed his preference at post-concert parties, which meant that he was no longer invited to some cities. In 1968, in a context made very difficult by the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and the demonstrations against the Vietnam War, Istomin felt obliged to accept the chairmanship of the Arts and Letters Committee for Humphrey. It was in this capacity that he was whistled at, a few weeks after the Chicago Convention, when he came onstage at the Lincoln Center to play Beethoven’s Fourth Concerto under Bernstein. Among the protesters, there were without doubt Republicans who supported Nixon, but also Democrats who felt that Humphrey had not made a clear commitment to stop the war in Vietnam. This political commitment consequently tarnished Istomin’s image to a certain degree with part of the public.

However, Istomin’s presence with American orchestras remained very strong throughout the 1960s. In 1964, he was invited twice by the Chicago Symphony (five concerts with Ehrling and Kostelanetz), by the Philadelphia Orchestra (six concerts with Ormandy), and by the Los Angeles Philharmonic (six concerts with Vandernoot and Katims). In the fall of 1968, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of his debut, he was invited by Philadelphia (Ormandy), New York (Bernstein), Los Angeles (Mehta) and the National Symphony (Mitchell). The rest of the season also took him to Detroit (Ehrling), Boston (Leinsdorf), Baltimore (Comissiona) and several less prestigious places. During this decade, Istomin expanded his concerto repertoire to a small extent: Mozart’s Concerto K. 491, the Beethoven Third, and two works which he rarely played, as very few orchestras were interested in featuring them in their seasons: Kirchner’s First Concerto and Szymanowski’s Symphonie Concertante.

He did not have enough time to develop his solo career in European countries, although France eventually opened its doors to him. A close relationship was established with the French Radio and Television orchestras. He was even slated to be the soloist for an American tour given by the Orchestre National de France, and conducted by Maurice Le Roux in the fall of 1967. This lack of time had an even more negative impact on his activity as a recitalist, since there was little room left for them. Above all, he had no time to tackle new scores. During this decade, he would add only two works to his repertoire: Stravinsky’s Sonata and Schubert’s Sonata in D major. As he was unable to propose new programs, Istomin gave only one recital at Carnegie Hall in 1964, performing Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit again, which he had not played for many years.

The prospect of the bicentennial celebrations of Beethoven’s birth in 1970 led to great excitement in the musical world. An idea began to stir in Istomin’s mind and in that of his two partners, of meeting a challenge head-on which no one had ever dared to take up before: that of performing the complete chamber music with piano, i.e. thirty-one works in eight concerts. It was one of the most publicized events of the Beethoven bicentennial celebrations. Istomin, Stern and Rose had six months of bookings for this adventure, the story of which can be found in another article. They could have devoted the entire year, but even so, it would not have been enough to satisfy all the interested organizers.

Columbia wanted to take advantage of this opportunity to record not only the complete Beethoven Trios, but also the Sonatas and Variations for violin or cello. It was a considerable task for Istomin, who was ready to take it on but who rightly feared that it would reduce his image to that of a chamber musician. He asked to record one or two Beethoven concertos to restore his reputation as a soloist, but Columbia refused. In consequence, Istomin decided not to continue with the complete Sonatas for violin and cello (four had already been recorded), agreeing only to complete the Trios. This caused a crisis within the Trio which was eventually overcome, but which left lasting marks. Above all, for Istomin it meant a definitive break with Columbia which would be of lasting damage for the remainder of his career.

Music

Johannes Brahms. Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, op. 83. Eugene Istomin, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Charles Munch. Concert in January 1960.

.

Franz Schubert. Sonata in D major D. 850, second movement (Con moto). Eugene Istomin. Recorded for Columbia in 1969.

.

Mendelssohn. Trio No. 1 in D minor Op. 49, the two last movements (Leggiero e vivace; Allegro assai appassionato). Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern, Leonard Rose. Live recording on December 11, 1961.