When Eugene Istomin agreed to take over the artistic responsibility of the Prades Festival from Sasha Schneider, he certainly did not realize the magnitude of the task ahead!

His first mission was to form an orchestra again. This was the dearest wish of Casals, who truly enjoyed conducting for the first editions of the festival. Of course, he would rely on the musicians who had already come to Prades and Perpignan, and who dreamed of returning, including Paul Tortelier and the great Franco-American oboist Marcel Tabuteau. To complete the group, he used his connections with the major American orchestras to hire top-class instrumentalists: Jacob Krachmalnick, concertmaster of the Philadelphia Orchestra; William Lincer, principal viola of the New York Philharmonic; and clarinetist David Glazer. Some distinguished soloists, such as Yfrah Neaman and Zvi Zeitlin, agreed to join the violin section simply for the privilege of playing under Casals. The level of the 1953 orchestra was quite exceptional.

As for the soloists, he had proposed two violinists to replace Schneider, Stern and Szigeti. The first was Joseph Fuchs, with whom he had played chamber music. Both of them had also been featured in a spectacular Beethoven concert at the Lewisohn Stadium with the New York Philharmonic. The second was Arthur Grumiaux, who had just been very successful on his first US tour and was Ysaÿe’s successor. On the piano side, there were the regulars: Clara Haskil (it was that year in Prades that she first met and played with Grumiaux), Rudolf Serkin and Mieczyslaw Horszowski. Istomin had added, with the blessing of Casals, his great friend William Kapell.

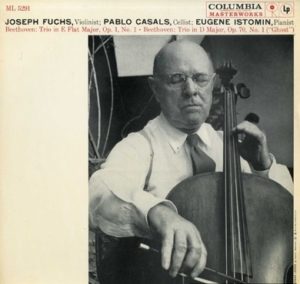

Istomin had also succeeded in convincing Columbia to continue the Prades recordings with Casals. In order to ensure that financial support would be extended, he planned that Casals would complete the two Beethoven series which were initiated in 1951: the Cello Sonatas with Serkin, and the Piano Trios with himself and Fuchs, who replaced Schneider. Most importantly, he had persuaded Casals to record Schumann’s Cello Concerto for the first time in his career, an amazing event!

What proved to be the most time and energy-consuming was the search for financial support from patrons and the coordination of the American festival committee. More than fifty private donors had contributed to the funding, among them some wealthy American families, but also musicians (Dimitri Mitropoulos and Leopold Mannes in particular). Istomin had even solicited his uncle Elias. The time devoted to these duties was at the expense, as he sometimes complained, of his work on the piano: he did not add any new concerto or solo works to his repertoire that year! It was also at the expense of his figure: numerous lunches and dinners were indispensable for the fund raising and he put on extra pounds. He also took care of advertising and press relations, ensuring a letter from Casals was published in the Saturday Review on March 28, 1953. Casals vigorously denied the rumor that had been circulating in the French press that he also intended to give concerts in Belgium and Switzerland, and by so doing, renege upon his commitment not to play in public as long as Franco remained in power and democracy was not restored in his country. .

Istomin would have to make two exhausting trips to Prades to clear up some issues with Casals. He was the one who, with the invaluable help of Madeline Foley, coordinated the programs, harmonized the repertoire, and scheduled the rehearsals and recording sessions. This resulted in a continuous exchange of letters and telegrams in which Casals often had to be reassured, as he worried about having to fulfil an overloaded schedule of concerts and especially recordings. To this end, Istomin often added a few words in French in his letters: “Calme toi, ça ira tranquillement” (Calm down, it will go smoothly). He and Madeline Foley arrived very early in May to prepare everything in the Abbey of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, which had no roof and was currently in the midst of an archaeological excavation. Casals had given up the Brahms Sonatas, scheduled around May 12, but did record Beethoven’s Sonatas (No. 1, 3, 4 and 5) with Rudolf Serkin between May 17 and 20, under the artistic direction of Istomin and Foley. .

The orchestra arrived on May 22 and the following week was dedicated to orchestra rehearsals and recording the Schumann Cello Concerto. Casals had thought of playing and conducting at the same time, but it proved to be impossible, as he would have had to play in front of the microphone with his back turned to the orchestra. Enric Casals, the Maestro’s brother, was therefore asked to conduct. A former student of Mathieu Crickboom (Ysaÿe’s main disciple), he had been principal second violin of the festival orchestras. He had considerable experience as a conductor, often assisting his brother in Barcelona in the 1920s and 1930s and continuing a career in Spain and abroad after the Civil War. But this time, he proved to be incapable of conducting this group of demanding musicians, who refused to record under him. It was Istomin’s responsibility to find a solution, and to call upon a great conductor. His first thought was of William Steinberg, who was unavailable, and then of George Szell, who had once made a fantastic recording of the Dvořák Concerto with Casals. Because Szell was already under contract with Columbia, this would have made things easier. However, several musicians of the orchestra, and in particular the concertmaster Jacob Krachmalnick, were in strong opposition. Krachmalnick had been Szell’s concertmaster in Cleveland and could not bear the contemptuous way Szell treated his musicians. In 1951, Krachmalnick had left Cleveland for Philadelphia. He knew that Ormandy was on holiday in Switzerland and could therefore come to Prades very quickly. Although Istomin had some reason to complain about Ormandy (who had never invited him back since 1943), he still thought that this was the best solution. He called Ormandy, who immediately agreed to come and conduct, even if he had to do it anonymously because of his exclusive contract with RCA. He did not ask for a fee, wishing to pay tribute to Casals. For a long time, the disc was published without mention of the conductor!

The orchestra arrived on May 22 and the following week was dedicated to orchestra rehearsals and recording the Schumann Cello Concerto. Casals had thought of playing and conducting at the same time, but it proved to be impossible, as he would have had to play in front of the microphone with his back turned to the orchestra. Enric Casals, the Maestro’s brother, was therefore asked to conduct. A former student of Mathieu Crickboom (Ysaÿe’s main disciple), he had been principal second violin of the festival orchestras. He had considerable experience as a conductor, often assisting his brother in Barcelona in the 1920s and 1930s and continuing a career in Spain and abroad after the Civil War. But this time, he proved to be incapable of conducting this group of demanding musicians, who refused to record under him. It was Istomin’s responsibility to find a solution, and to call upon a great conductor. His first thought was of William Steinberg, who was unavailable, and then of George Szell, who had once made a fantastic recording of the Dvořák Concerto with Casals. Because Szell was already under contract with Columbia, this would have made things easier. However, several musicians of the orchestra, and in particular the concertmaster Jacob Krachmalnick, were in strong opposition. Krachmalnick had been Szell’s concertmaster in Cleveland and could not bear the contemptuous way Szell treated his musicians. In 1951, Krachmalnick had left Cleveland for Philadelphia. He knew that Ormandy was on holiday in Switzerland and could therefore come to Prades very quickly. Although Istomin had some reason to complain about Ormandy (who had never invited him back since 1943), he still thought that this was the best solution. He called Ormandy, who immediately agreed to come and conduct, even if he had to do it anonymously because of his exclusive contract with RCA. He did not ask for a fee, wishing to pay tribute to Casals. For a long time, the disc was published without mention of the conductor!

Istomin dealt with large and small issues on a daily basis. The most serious one was the “strike” by the orchestra in protest against the accumulation of recordings without financial compensation. French Radio came for the first time (with the exception of the additional concert on 18 June 1950 in Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa) and recorded seven concerts for multiple broadcasts in all the European countries, which was a modest, but not insignificant source of revenue for the festival. It also resulted in important media coverage, as the French national press continued to ignore Prades. At the same time, Columbia had left a crew for the duration of the festival to record a few chamber music works and as many symphonic works as possible. The orchestra agreed to record the Schumann Cello Concerto, but the Schubert Fifth Symphony could not be completed and released (Sony eventually published it forty years later).

“There were tense discussions. Some members of the orchestra disappointed me. Even the most ‘Casalsian’ of musicians, like the double bass player June Rotenberg, who was completely in love with Casals, had played the “sans-culottes”! The union reflexes of American musicians had taken over. I understood the musicians’ position, but I still thought it was stupid not to make these recordings. What a pity! In fact, Columbia’s profit was supposed to be very high, but in the classical music business it was never that high, even back then! The musicians didn’t realize that. Columbia had invested another $25,000 (like $250,000 today) to allow the festival to be held. The American musicians (the cream of the great American orchestras) were almost unpaid. They had come for Casals. It would probably have been enough for Casals to speak up and say: ‘Do it for me and for Music!’ And they would have done it. But Casals was too sensitive and proud to do that. In 1950, we all decided, soloists and orchestra musicians, to receive only a symbolic fee and to give all the royalties to Casals. This was justified at the first festival (which was supposed to be unique!), as a kind of tribute, but for the following festivals it would have been normal to share the royalties. I should have changed the contracts in 1953 when I was in charge of them. Casals let this situation take root, certainly not for his own benefit (his way of life was incredibly modest), but because of the many obligations he faced, especially his financial support of the Spanish refugees and the constant demands of his family.”

This first experience was one of great learning for Istomin, although it proved to be very hard to live through. He undoubtedly lost a few idealistic illusions about human nature, but everything went well in the end. The momentarily tense atmosphere quickly calmed down and the artistic success was fantastic. The only negative point was on the financial side. The cost of the orchestra had been exorbitant (it had been necessary to pay for travel expenses and a five-week stay for about thirty American musicians). It could not be balanced by the proceeds from five symphonic concerts!

This first experience was one of great learning for Istomin, although it proved to be very hard to live through. He undoubtedly lost a few idealistic illusions about human nature, but everything went well in the end. The momentarily tense atmosphere quickly calmed down and the artistic success was fantastic. The only negative point was on the financial side. The cost of the orchestra had been exorbitant (it had been necessary to pay for travel expenses and a five-week stay for about thirty American musicians). It could not be balanced by the proceeds from five symphonic concerts!

The very existence of the festival was in danger. Istomin received the dedicated support of friends and musicians. Paul Paray, for example, solicited some wealthy people from Detroit. A drastic decision was made about the French committee, which was a continuing source of endless discussions and quarrels. Istomin and Foley recommended that Casals dissolve it and rely exclusively on the American committee, which consisted in his most loyal friends: Russell Kingman, Rosalie Leventritt, Mieczyslaw Horszowski, Leopold Mannes, Cameron Baird… They suggested to Casals that he organize a festival without orchestra, with eight concerts dedicated entirely to Beethoven’s chamber music with piano. Casals was delighted to accept.

The 1954 Festival

The concerts took place again in the Church of St. Peter, as the Abbey of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa was undergoing reconstruction. Istomin divided the programs between the three pianists who were the closest to Casals: Serkin, Horszowski and himself (Haskil was unavailable). Out of respect to his two elders, and anxious not to put himself forward while he held the artistic direction, he entrusted them with a few solo piano works and did not play any. There was, of course, the complete cycle of Cello Sonatas and Variations, for which the three pianists took turns along with Casals. Two violinists shared the complete Violin Sonatas and Trios – Joseph Fuchs and Szymon Goldberg, a fine musician who replaced Grumiaux, who was unable to free himself for this event. The only French participation for this 1954 edition was that of the most famous string trio ensemble, the Trio Pasquier. All the musicians received the same (very modest) fee. French Radio was again present, broadcasting seven of the eight concerts) and brought a significant financial contribution, so that for the first time the festival’s financial results were profitable. The atmosphere was full of fervor and enthusiasm. A feeling of energy, youth and freshness permeated the entire festival.

Thanks to the radio broadcasts of the previous festival, the European public arrived in large numbers from all over Europe and French newspapers discovered the festival. Bernard Gavoty, the distinguished critic of Le Figaro, apologized to his readers for not having realized this earlier: he had been told that Casals was a mere shadow of himself and that it would be better if he relied upon his memories of past concerts or listened to his old recordings. Here is what he reported when he came to Prades: “Time acts on Casals as it does on a great wine: it exalts it by making it even simpler. Absolutely intact instrumental capacities; Carthusian simplicity; virility of accents, a unique way of establishing the climaxes by making them wait a little, a sound that is not very powerful but sovereign; imperious softness, inexorable; rhythms as natural as the beating of the heart… It is better than beautiful, it is real.” There were few Americans, but some great European figures were present, including Queen Elisabeth of Belgium and Marie José of Italy, Prince Pierre and Prince Rainier of Monaco, and President Auriol (who had just completed his term of office). Many musicians had also come, a bit in the sense of a pilgrimage. To Istomin, Gieseking’s discrete presence when Serkin played two sonatas with Casals and the Sonata Opus 109 seemed to be a kind of declaration of allegiance, respect, and even a form of repentance.

The 1955 Festival

The previous year, Istomin had already begun to delegate some administrative tasks of the festival. This occurred even more in 1955, with the appointment of Enric Casals as General Secretary. Nevertheless, he continued to assume the artistic direction with Madeline Foley, and of course, in close association with Casals. He gave Casals all his affection and support during the very difficult moments before and after the death of Frasquita Capdevila, his companion for twenty years. In the process of caring for her day and night for several months, Casals had allowed himself to become overwhelmed by fatigue and sadness. Istomin urged him to continue playing and teaching, and to think about the future in preparation for the next festival. This edition was dedicated to Bach, Schubert and Brahms. To ensure public and financial success, the festival dates were postponed to July. This made it impossible for Serkin to take part, as the Marlboro Festival began on July 3rd. Despite the presence of the young Swiss pianist Karl Engel, Istomin was forced to take on a very heavy schedule. For Brahms, he performed the three trios for piano and strings, the Trio with clarinet, a violin sonata and a clarinet sonata. In addition to Casals, his partners were Yehudi Menuhin, who took part for the first time, and David Oppenheim, who was delighted to play with Casals. For Schubert, he played the First Trio with Sándor Végh and Casals and accompanied his friend David Lloyd in Die schöne Müllerin as well as in some isolated Schubert and Brahms songs. All this took place within the space of ten days!

Once again, the festival was a huge success. On August 7, 1955, The New York Times published an important article by Paul Moor, entitled Casals in Prades and subtitled “The cellist, now 78 years old, remains a unique symbol, both as a man and as a musician”. Moor reported the great enthusiasm of the public: nearly all the concerts were sold out. He expressed his immense admiration for Casals who, after the ordeal of Mrs. Capdevila’s illness and death, had been able to recover an incredible strength and dynamism. Moor also implied that the 1956 festival was already in preparation and that the project was very ambitious: to bring together an orchestra and a choir to celebrate the bicentenary of Mozart’s birth, and to give Casals the opportunity to realize his dream of conducting the St Matthew Passion.

These ambitious projects would not be carried out. Eugene Istomin and Madeline Foley left the festival after having a falling out with Casals! Here is the account of this clash, as confided to Bernard Meillat in 1987 by Istomin himself: “Tortelier and Madeline were ‘in competition’ during the 1952 Festival but they had remained very close friends. They had shared the chamber music works for the concerts and recordings and played next to each other in the small orchestral ensemble. In 1953, Madeline had defended Tortelier. She felt that he deserved to be better paid, with his qualities, dedication and family responsibilities. He had played in the festival orchestras as well as in chamber music concerts and had also been very helpful in the preparation of the festivals. I myself was convinced that Casals preferred Tortelier to all the other cellists at that time. Tortelier had not participated in the 1954 festival because there was no place for a second cellist, or in the 1955 festival because he had gone to spend a year on a kibbutz in Israel. When we presented the projects for the 1956 program to Casals, Madeline and I proposed to invite Paul Tortelier again and give him something important, perhaps a Bach suite. It would highlight him in a spectacular way and might boost his career. Casals refused. It seemed to me like a banal weakness, a lack of noble-mindedness that really upset me: how could this god of goodness and generosity be capable of meanness? I was sarcastic and Casals couldn’t stand my irony. It turned into an argument. The other people in the house looked at me as if I were the devil himself, for daring to raise my voice to the Maestro. Madeline didn’t say a word. She was completely stunned, almost admiring that I dared to stand up to Casals! It simply proved that he was human – and all great performers have this kind of reaction, especially as they age and fear decline. I left immediately after my last concert, without even saying goodbye to Casals.”

Of course, this quarrel did not last. A few weeks later, Istomin wrote a long letter to Casals. It was not an apology, but about what they meant to each other, and a reiteration of the depth and indestructibility of their bonds. Casals immediately replied with a very affectionate letter, urging him to come and play with him at the next festival. This turned out to be impossible due to the long tour Istomin was about to undertake in the Far East at the request of the State Department. Istomin expressed his deep regret at not being able to participate. He brought his financial support to the festival by offering the fees of the recitals he had given in Mexico, a country dear to the heart of Casals for having welcomed tens of thousands of Spanish Republican refugees with open arms. On June 20, he wrote to him from Manila, wishing him “Good luck” for the festival and telling him how much he was looking forward to joining him for the first Puerto Rico Festival in the spring.

Istomin concerts at Prades Festival (1953-1955)

1953

July 2 (additional concert, in benefit of St Michel de Cuxa Abbey). Brahms, Cello Sonata No. 1 in E minor Op. 38, with Pablo Casals.

July 3. Bach. Trio Sonata in G Major BWV 1039, with John Wummer and Bernard Goldberg, flute. Beethoven, Trio in E flat Major Op. 1 No. 1, with Joseph Fuchs and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

July 3. Bach. Trio Sonata in G Major BWV 1039, with John Wummer and Bernard Goldberg, flute. Beethoven, Trio in E flat Major Op. 1 No. 1, with Joseph Fuchs and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

July 5. Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 4 in G Major Op. 58, with the Prades Festival Orchestra conducted by Pablo Casals.

July 7. Bach, Gamba Sonata No. 1 in G Major BWV 1027, with Pablo Casals. Beethoven, Trio in D Major Op. 70 No. 1 “Ghost”, with Joseph Fuchs and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

July 8-9. Recordings for Columbia, with Joseph Fuchs and Pablo Casals. Beethoven, Trio in E flat Major Op. 1 No. 1 (on July 5). Trio in D Major Op. 70 No. 1

1954

June 7. Beethoven. Violin Sonata No. 1 in D Major Op. 12 No. 1; Violin Sonata No. 4 in A minor Op. 23, with Joseph Fuchs. Cello Sonata No. 2 in G minor Op. 5 No. 2, with Pablo Casals. Trio in G Major Op. 1 No. 2, with Joseph Fuchs and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

June 13, additional concert, in benefit of the restoration of the St Peter’s Church organ. Beethoven. Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major Op. 47 “Kreutzer”, with Szymon Goldberg. Cello Sonata No. 2 in G minor Op. 5 No. 2, with Pablo Casals.

June 16. Beethoven. Trio in B flat Major Op. 11, with Szymon Goldberg and Pablo Casals. Violin Sonata No. 9 in A Major Op. 47 “Kreutzer” and Violin Sonata No. 3 in E flat Major Op. 12 No. 3, with Szymon Goldberg. Trio in C minor Op. 1 No. 3, with Szymon Goldberg and Pablo Casals.

June 22. Beethoven. Violin Sonata No. 2 in A Major Op. 12 No. 2; Violin Sonata No. 8 in G Major Op. 30 No. 3, with Joseph Fuchs. Variations on “Bei Männern, welche Liebe fühlen”; Cello Sonata No. 4 in C Major Op. 102 No. 1, with Pablo Casals; Trio in B flat Major Op. 97 “Archduke”, with Joseph Fuchs and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

1955

July 3. Brahms, Violin Sonata No. 1 in G Major Op. 78, with Yehudi Menuhin; Trio for Piano, Clarinet and Cello in A Major Op. 114, with David Oppenheim and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

July 8. Brahms, Trio No. 1 in B Major Op. 8, with Yehudi Menuhin and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

July 9. Brahms, Trio No. 2 in C Major Op. 87 and Trio No. 3 in C minor Op. 101, with Yehudi Menuhin and Pablo Casals. Recorded concert.

July 10, additional concert in benefit of St Peter’s Church. Brahms, Clarinet Sonata No. 1 in F minor Op. 120 No. 1, with David Oppenheim.

July 12. Schubert, Trio in B flat Major D. 898, with Sándor Végh and Pablo Casals; Die schöne Müllerin, with David Lloyd, baritone. Recorded concert.

July 13. Schubert, 2 Lieder from Der Winterreise; Brahms 3 Lieder (Op. 71 No. 5 ; Op. 86 No. 6 ; Op. 33 No. 10) with David Lloyd, baritone.

Music

Three exceptional live recordings at the Prades Festival

Bach, Gamba Sonata No. 1 in G Major BWV 1027, the two last movements (Andante; Allegro moderato). Pablo Casals, Eugene Istomin. Live recording on July 7, 1953.

.

Beethoven. Cello Sonata No. 2 in G minor Op. 5 No. 2. Eugene Istomin, Pablo Casals. Live recording on June 7, 1954.

.

Schubert. Four lieder from Die schöne Müllerin D. 795: Wohin? Halt! Danksagung an den Bach. Am Feierabend. David Lloyd, tenor. Eugene Istomin. Recorded live on July 12, 1955.