In many articles on this site, mention has been made of pianos, particularly in the article written by Tali Mahanor, who was his devoted piano tuner for the last fifteen years of his career. In it, she recounts the adventures of two Steinway pianos which Istomin played at that time, the CD-86 and CD-383 (the prefix CD being attributed to the pianos of Steinway’s “Concert Department”). Here is the story of the relationship between Istomin and Steinway.

The 1940s and 1950s

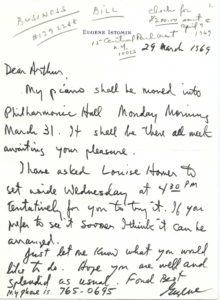

“It’s always wonderful to play on a Steinway.’’ Istomin signed this declaration on November 12, 1943, a few days before his spectacular debut with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. He thus officially became a “Steinway pianist” and a member of the prestigious family of great pianists, dating back to Liszt! Already, while still a student at the Curtis Institute, Steinway had provided him with a B model (2.11 meters long). When he moved to New York with his parents, Steinway sent another B model that he kept for a long time in his room, and which was used by friends who were hosted for a few days when they were on tour (like Clara Haskil), or who stayed for a much longer time (like Pinchas Zukerman when he was studying at Juilliard).

Despite the misadventure of his first concert at Carnegie Hall (the piano he had chosen was changed at the last minute), a friendly relationship was established between Steinway and Istomin, which would never falter. When he moved out of his parents’ apartment to live on his own, he was entrusted with a concert grand piano (Model D-274) on loan, free of charge, at home. In addition, he could book another piano and have it sent anywhere in America, paying only for the cost of transport. Thus, the famous CD 199, dear to the OYAPs, toured the United States for more than a decade, with a mutually agreed-upon schedule which allowed each of them to benefit from this magical piano for their most important concerts.

The locale where all the concert pianos were stored was in the basement of the Steinway building – now a skyscraper – at 57th Street, very near Carnegie Hall. It was a special place for all pianists, who came to choose an instrument for a future concert or to try out pianos which were new or had just been restored. Some pianos were reserved for the exclusive use of certain great pianists, such as Horowitz or Serkin, and it was out of the question to touch them. Slots could be reserved for practice between 4:30 p.m. (the time technicians and tuners stopped working) and 11 p.m. As Gary Graffman recounts, for the generation of great American pianists who appeared in the 1940s, the Steinway basement was both a workshop and a clubhouse where they met to listen to and pitilessly criticize each other, followed by endless discussions in a few nearby restaurants or cafés. .

. .

The ivory crisis

In 1958, Steinway decided to give up the use of ivory for its piano keys. The management was afraid of being accused of encouraging elephant poachers. Research had been carried out to develop a synthetic coating that allegedly had the same qualities as ivory.

The small community of concert pianists tried to protest. The ivory keys could already become slippery because of sweaty hands, due to stage fright or perspiration, but it was much worse with the new material! Istomin took the lead in the revolt. He claimed that the plastic keys triggered an allergic reaction which caused his fingers to sweat even more. Supported by his OYAP friends, he campaigned for the idea of leaving available a number of concert pianos with ivory keys. Nothing could change Steinway’s decision. All new pianos were equipped with synthetic keys and older pianos gradually had their ivory keys replaced. For a moment, Istomin considered giving up being a “Steinway pianist” as a protest, but the consequences of such a decision were dramatic (no Steinway piano available anywhere!) and he most definitely did not want to play on a Bösendorfer, Mason & Hamlin or Yamaha!

Each pianist dealt with the situation as well as he could, using hairspray, rosin, very fine glass wool, and even sandpaper, while trying to be as discreet as possible. One day, Istomin was denounced for having methodically scratched the keys of a brand new keyboard. He had to pay back the damages.

The Hamburg Steinway

In addition to the ivory problem, there was a feeling in the 1960s that the quality of the Steinways was in decline. Many pianists complained about recent instruments that were too bright and not very singing. Those who gave concerts on both sides of the Atlantic came to prefer the Steinway made in Hamburg.

Eventually, when Istomin complained about not being able to play on an ivory keyboard, Henry Z. Steinway, one of the founder’s great-grandsons who presided over the company from 1956 to 1977, suggested he go to Hamburg, where ivory keyboards were still being manufactured. Istomin followed his advice and bought a Hamburg Steinway (there was no question of him being offered one, but he did pay a very favorable price).

Istomin was very happy with his purchase. Occasionally he had this piano transported for his concerts in New York. The pianist friends who visited him were very enthusiastic and found its sound magnificent, remaining warm and singing, even in the treble. Even Arthur Rubinstein asked to borrow it for a concert at the Lincoln Center, which caused a diplomatic incident. Henry Steinway was planning to attend the concert with the director of Steinway Hamburg and was furious when he got wind of the project: what an affront for him to have an instrument from Germany on the stage! Rubinstein was asked to relinquish his request, Istomin called to order, and the piano was unceremoniously returned to Istomin’s apartment. Rubinstein apologized to Istomin and sent him a cheque of $200 for the cost of transportation – a cheque which Istomin did not deposit and kept as a souvenir.

The big problem with the Hamburg Steinways of that time was their fragility and inability to stay in tune. Their wood and manufacturing were not suitable for America’s extreme climatic conditions. One of the pianos that Istomin enjoyed playing on the most was a Hamburg Steinway on the stage of the Teatro Colón, but it went out of tune before the end of the concert. Istomin had had his Hamburg Steinway restored twice, but to no avail. With a heavy heart, he decided to part with it. Thornton Trapp, Istomin’s secretary and page turner, described the piano’s departure on May 4, 1970, just before the Trio’s big Beethoven tour: “Early this morning, I got up to look at the piano, firmly attached, being passed through the window upside down. A trip from the twelfth floor to the ground, at a cost of seven hundred and fifty dollars. People on the street applauded him after his soft landing. Eugene couldn’t stand this separation, he fled to the Steinway basement. He soon found his successor, a Steinway B from New York, with whom he had quickly fallen in love.”

Being a “Steinway pianist”

After this delicate period, his relationship with Steinway once more became very cordial. Istomin had made friends with the successive directors of the concert piano department, David Rubin and especially Peter Goodrich.

After this delicate period, his relationship with Steinway once more became very cordial. Istomin had made friends with the successive directors of the concert piano department, David Rubin and especially Peter Goodrich.

To be a “Steinway pianist” was a great privilege, all the more so as Istomin had forged links with many Steinway branches around the world. If he stayed a few days in a city, an upright piano was usually installed in his hotel room to allow him to practice at his discretion. When Istomin came to Europe, he used to stay a few days in Paris to recover from jetlag. Each time, he had a grand piano sent to the Hôtel de la Trémoille by the French dealer Hanlet, and was given the key to the store where the concert pianos were kept so that he would be able to come and play outside the opening hours.

The CD-18

The CD-18 was one of the two pianos that Steinway kept in reserve for Horowitz in the late 40s and 50s, and which had been regulated especially for him. It was the ideal piano for playing Rachmaninoff: the key dip was shallow, which allowed for very rapid passagework and quick, light accenting, and the sonority and dynamic range were exceptional. It was not a piano to be put into all hands, requiring as it did such fantastic control!

When Istomin recorded the Rachmaninoff Second Concerto, Horowitz lent him his piano, the CD-18. Horowitz had never played this concerto in public before and knew with certainty that he would never perform it. It seemed to him that Istomin was the pianist who could best do justice to this work – and he therefore made his piano available to him, which he had previously never done for anyone. It was a mark of trust of which Istomin was very proud.

Later the piano was installed permanently at Carnegie Hall and then at Lincoln Center. In 1972, Steinway brought it back to the Concert Department after restoring it and installing synthetic keys. Istomin was very disappointed. He told Steinway that if it were possible to replace the keys with ivory, he was determined to buy it. A few years later, after Henry Steinway’s departure and the takeover by CBS, the ban on ivory became more flexible, while respecting the legislation. Steinway had established a partnership with the German firm Kluge, who provided an ivory keyboard for the CD-18 which was installed in 1983. Istomin saw the keyboard at the factory, and at first glance noticed that the keys were wider than on the American keyboards. Taken aback, the technicians checked. The width of an octave was effectively 1.5 mm wider!

Steinway was able to modify the keyboard to Istomin’s specifications, and he kept the piano in his living room for twenty years. After his death, Marta Casals-Istomin kept it with her for a few years and eventually, on the advice of Tali Mahanor, entrusted it to the Tippet Rise Art Center in Montana.

Music

Rachmaninoff. Concerto No. 2 in C minor Op. 18, second movement. Eugene Istomin. Philadelphia Orchestra. Eugene Ormandy. Recorded by Columbia in April 1956. Istomin was playing the Steinway CD-18!

Audio Player