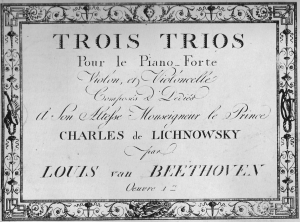

The text below is an article written by Eugene Istomin, which appeared in several papers, including the magazine Music in 1971. The success of the Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio had challenged conventional thinking about chamber music and their performers. The many concerts and recordings of the celebrated Trio, coupled with the great challenge of performing the complete piano chamber music by Beethoven all over the world throughout the bicentennial year, made mentalities evolve, but Istomin thought it was still necessary to drive the nail into the matter.

There is still a certain amount of skepticism among managers and the less informed members of the public when musicians with major solo careers decide to take time from their busy schedules to make chamber music together. Is not the virtuoso by his very nature unable to blend his strong musical personality with others equally strong?

To the professional musician this attitude has always been a source of amusement. Music is music after all. No performer whose musical life centers on the masterworks of the 18th and 19th centuries is interested only in one sonata or two concerti by these composers.

For example, a musician who is not interested in Schubert’s or Beethoven’s total output should not touch the works involving his own instrument whether they be the solo works, trios, quintet, or lieder. There is no qualitative difference in these works; and therefore, it is absurd to suppose a pianist can play the solo sonatas well and not be good in chamber music. Conversely, one could say if he is weak in the trios, he will be equally weak in solo sonatas.

If Beethoven had written a beautiful piece for trombone, coloratura and piano, I should want to play it. I think we all feel this way. The notable and few exceptions are geared to other repertory and to other aims.

If this is why we do it, the how is not so easy. To find your partners in a serious musical relationship is as important – and as delicate – as picking out your wife and your close friends. There is no such thing as chamber music technique. The technical problems are actually less demanding than in solo playing, since one has fewer notes to play, but these problems are of the same nature.

If this is why we do it, the how is not so easy. To find your partners in a serious musical relationship is as important – and as delicate – as picking out your wife and your close friends. There is no such thing as chamber music technique. The technical problems are actually less demanding than in solo playing, since one has fewer notes to play, but these problems are of the same nature.

Granted the instrumental technique, it is the approach to musical matters which is paramount. If mutual feeling about the music is there, the matters of balance, of this or that line or note predominating, are easily solved.

With my partners – Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose – I feel this rapport. There is a give-and-take, of course, but we never play your way or my way. If we could not play a work our way, we just would not play it. So far this has never happened. Disagreements, though they may be vociferous and often highly melodramatic, must in real substance be extremely minor when it comes to major musical matters. Either people are in agreement or they do not play together.

Chamber music came to me, I suppose, naturally. Trained under Serkin as I was, Bach, Mozart, Haydn, Schubert, Schumann, Brahms and Chopin have been central to my musical experience since I was a child. All except Chopin have an extremely important output of ensemble music.

At Curtis we played a certain amount of repertory, of course, but it was only after my graduation – in 1944 and 1945 – that I made two big tours with Adolf Busch and his Chamber Players, performing Bach and Mozart concerti across the country. From Busch, as from Serkin, I learned immeasurably about all kinds of music including chamber music, which we often played together informally.

During the years that followed I played recitals and one concerto after another with orchestras all over the place. Then in 1949 Alexander Schneider asked me to play with him complete cycles of the Beethoven violin and piano sonatas in Chicago, Harvard and New York. These performances, which brought me great joy, led also to the invitation to the first Casals Festival at Prades in 1950.

As the youngest artist invited, I was in awe of the great man, as probably was everyone there. That festival in 1950 had a profound influence on my musical thought and personal development. After it was over, I remained in Prades the rest of that summer and returned many times again in later years to be near the man who personified so many of my ideals, as well as those of my closest colleagues. Curiously enough, although his influence was very broad it was never direct. While we played for our pleasure practically the entire standard repertoire of piano chamber music, and quite a bit publicly at subsequent festivals, I cannot remember his ever criticizing me or any of his other partners. Even when I would come to him with a specific musical problem in my own solo playing, he would listen to me play and was ecstatic over everything, leaving me very flattered but still heavy with problems and slightly exasperated. What then was the meaning and value of these contacts with the great man?

Taste, depths of feeling, love – big words, big things – and none of them can be learned or rehearsed. They can however be drawn out and encouraged by revelation. And that was the Casals experience. I am reminded of Rilke’s observation that great works of art can only be understood through love. That is one meaning of revelation. It is also the kindling spark which is the beginning and the end of all inspired music making. Whether solo or any instrumental configuration, it remains one music.

Isaac Stern was the young violinist at the festival. Besides our solo performances, we were programmed together in one chamber work. We enjoyed that collaboration and enlarged it during the second Festival the next year. At the third festival we were already talking in terms of our eventual Trio, with Leonard Rose as the ideal cello partner of our generation.

By 1961, we had taken much time to work together, and our appearances in Israel, London and New York, brought us to the conclusion that the Trio was a source of real inspiration and therefore of artistic necessity to us. Now we give several weeks a season to it.

I must say of our Trio that we do begin with an advantage. Stern’s and Rose’s vibratos and sonorities match each other beautifully. Technical execution is a minor matter for us all since, as I have said, we are all used to the harsher rigors of solo playing. It has been said that our chamber music is not chamber music – it is too big. Perhaps – but then you might have to conclude that “big” trios, like The Archduke are too massive for the medium of chamber music. Personally, I feel like playing “gigantic” works “gigantically” and small scale works “intimately”. Sometimes both approaches are required in a single work. Also, since it has been said that we are all strong personalities (I am not sure I know what this means since it is hard for me to conjure up an artist without an identity or an ego) it is a blessing that we generally see eye-to-eye and blend together in some occult way. We do not try to do it, we just do it. And we become, one might say, a three-sided unity.

Eugene Istomin

Music

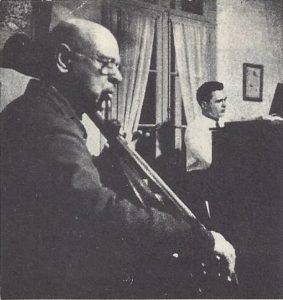

Beethoven. Trio in D major Op. 70 No. 1 “Ghost”. Eugene Istomin, piano; Isaac Stern, violin; Leonard Rose, cello. Filmed by the French Television in 1970.