The story of Istomin’s concerts in France is quite strange. It is a succession of periods with intense activity and complete absence, which can only be explained by the unpredictable political context of French musical life.

His debut in Paris on May 16, 1950, had been very well received. René Dumesnil, the critic of Le Monde, thanked Paul Paray “for having allowed the young 23-year-old pianist Eugene Istomin (a name to remember) to be heard, and for having accompanied him with such consummate art in Beethoven’s Concerto in G Major. Eugène Istomin has a deep understanding of the secrets of virtuosity, but more than this, he has something even better to offer: a personality which, however strong it may be – at times reminiscent of Kempff – knows how to be put to intelligent use in the service of the masters he interprets.” In the cities of Lyon, Vichy (where the orchestra’s principal flute was none other than Jean-Pierre Rampal) and Marseille, the public responded with enthusiasm. The only false note came from a critic in Lyon who called him a “typically American pianist with fingers of steel who plays like a typewriter, and who is totally devoid of any musical sensitivity.” This same critic added: “But where did he find these incredible cadenzas? There are limits to bad taste!” Istomin had actually played Beethoven’s original cadenzas… He kept the article, which remained a permanent source of amusement throughout the Prades festival!

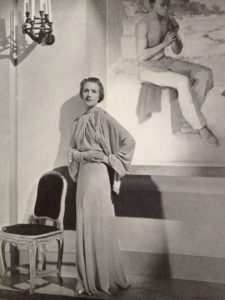

Despite an extremely promising debut and his participation in the first six Prades festivals (which continued to be stubbornly ignored by French critics for years), Istomin had virtually no engagements in France until 1963, whereas he was regularly invited to the United Kingdom, Switzerland and Italy. Perhaps he should have adopted the suggestion by Marcel de Valmalète, the top French manager who had welcomed him onto his roster, thanks to the support of Paul Paray: to perform for free in the salons of high Parisian society in order to make a name for himself, which Istomin flatly refused, finding this suggestion anachronistic and unworthy of consideration! At the end of the 1940s, this was still the best way to make oneself known and to launch a Parisian career. The most famous salon, that of Marie-Blanche de Polignac, hosted Arthur Rubinstein, Lili Kraus, Dinu Lipatti and Leonard Bernstein, among many other great musicians! Thanks to the Trio, Istomin came to France in the summer of 1963 to take part in several prestigious festivals: Aix-en-Provence, Divonne (two concerts), and Menton, where he played four chamber music concerts as well as a concerto with the Northern Sinfonia conducted by Milton Katims. French Television interviewed the members of the Trio and filmed them playing the Schubert Trio in B flat. This gave the first real tentative boost to his French career, leading to invitations by the Radio orchestras (the Orchestre National with Paul Kletzki in 1965 and the Orchestre Philharmonique de l’ORTF with Ottavio Ziino in 1967).

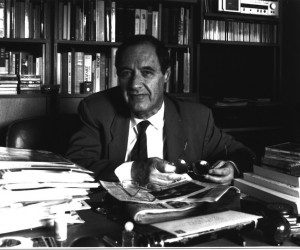

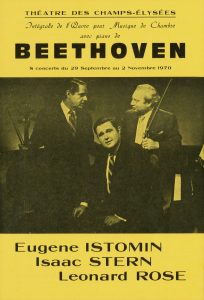

The situation completely changed in 1970 when the Trio gave its famous Beethoven cycle at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. French Television was determined to celebrate Beethoven’s Bicentennial with a great deal of ambition. It was decided to broadcast a weekly program in prime time with outstanding musicians performing major works by Beethoven. The person responsible for this ambitious approach was a former pianist called Pierre Vozlinski. He asked Istomin, Stern and Rose to film the complete Trios (including the two cycles of variations that were never broadcast and which were destroyed). He admired Istomin as a pianist, and the two men became friends. Many projects resulted from this mutual esteem and friendship: a long and captivating interview of Casals in 1972, the idea of reviving the Orchestre de Chambre de l’ORTF with Sasha Schneider as principal guest conductor and, of course, many concerts and recordings. In the span of eight years, Istomin gave ten concerts and recorded seven concertos and a significant part of his solo piano repertoire for television or radio. Vozlinski, who was also responsible for hiring Bernstein, Celibidache, Ozawa and Maazel as musical directors or principal guest conductors of the Orchestre National, was fired in 1981. Istomin would not be invited again by the French Radio until 1997.

The situation completely changed in 1970 when the Trio gave its famous Beethoven cycle at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. French Television was determined to celebrate Beethoven’s Bicentennial with a great deal of ambition. It was decided to broadcast a weekly program in prime time with outstanding musicians performing major works by Beethoven. The person responsible for this ambitious approach was a former pianist called Pierre Vozlinski. He asked Istomin, Stern and Rose to film the complete Trios (including the two cycles of variations that were never broadcast and which were destroyed). He admired Istomin as a pianist, and the two men became friends. Many projects resulted from this mutual esteem and friendship: a long and captivating interview of Casals in 1972, the idea of reviving the Orchestre de Chambre de l’ORTF with Sasha Schneider as principal guest conductor and, of course, many concerts and recordings. In the span of eight years, Istomin gave ten concerts and recorded seven concertos and a significant part of his solo piano repertoire for television or radio. Vozlinski, who was also responsible for hiring Bernstein, Celibidache, Ozawa and Maazel as musical directors or principal guest conductors of the Orchestre National, was fired in 1981. Istomin would not be invited again by the French Radio until 1997.

Making a career in Europe, and more particularly in France, was not easy for American musicians. To announce Istomin’s recital at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in February 1971, Claude Samuel published a portrait and an interview entitled “There is more than just Van Cliburn”. This eminent musicologist and journalist knew that the French public considered Van Cliburn, who without a doubt was brilliant in Tchaikovsky, to be a mere virtuoso who asked for astronomical fees, and that “Byron Janis was also ultimately too ‘American’.” In addition to the prejudice against superficial virtuosity, there was also the political context, with feelings of anti-Americanism aroused by de Gaulle which had been exacerbated by the war in Vietnam. Claude Samuel, fearing that the public would immediately reject Istomin on the pretext that he came from the other side of the Atlantic, assured them that Istomin had nothing in common with van Cliburn, and that he was a genuinely great musician! This recital was a great success indeed. Marie-Rose Clouzot published a rave review in Le Guide Musical: “What a wonderful performer! And how sorely one is tempted, at the end of such a concert, to shout not bravo, but thank you… (He) interpreted Schubert’s Sonata as though he were improvising in accordance with his own feelings, with a sovereign freedom of rhythm, never ‘metronomic’, in which the omnipresent sense of rubato is indiscernible.” She was even more enthusiastic about the Waldstein Sonata: “For once, here is a pianist who really plays this Moderato finale almost Allegretto and not Vivace, while at the same time unleashing its intense spirituality. The ovation that greeted the astonishing conclusion, a flowing torrent of light, was fully justified.”

This decade, rich in concerts and recordings, came to a sudden end in 1981. Predictably, the next directors of the ORTF music department no longer invited the artists whom Vozlinski had asked to come on a regular basis. Vozlinski, who was currently general manager of the Orchestre de Paris, was powerless to override the veto of his music director Daniel Barenboim, who was against Istomin being invited. Only André Furno invited him twice to appear in his 4-Star Piano series. At Stern’s suggestion, Istomin left Valmalète for Michael Rainer. He returned to Valmalète in 1985, but was not given any concrete support.

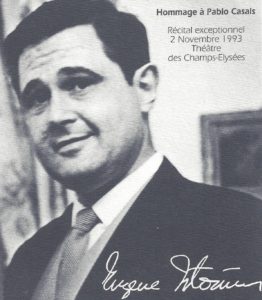

In the early 1990s, the Evian Festival and a Beethoven recital at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées put Istomin back at the forefront of French musical life. The press seemed to rediscover him. Pierre Petit in Le Figaro entitled his review “Beethoven in Majesty”. Istomin was invited by several regional orchestras (Orchestre National de Lille under Jean-Claude Casadesus, Orchestre National de Bordeaux-Aquitaine, Orchestre de Provence-Côte d’Azur and Orchestre de Besançon) and by the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France. There were also about twenty recitals, including two in Paris, in 1993 and 1996. It was a nice bright spot but did not lead to the hoped-for new momentum as one would have expected.

Recitals at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées

1971, February 8. Haydn, Sonata in A major Hob.XVI:12; Beethoven, Sonata No. 21 Op. 53 in C major “Waldstein”; Schubert, Sonata in D major D. 850.

1973, January 18. Beethoven, Fantasy in G minor Op. 77; Schubert, Impromptus Op. 90, No. 2 & 3 ; Brahms, Variations on a Theme by Handel Op. 24; Debussy, Préludes; Chopin, Ballade No. 4.

1991, October 30. Beethoven, Fantasy in G minor Op. 77; Sonata No. 14 in C sharp minor Op. 27 No. 2 “Moonlight ”; Sonata No. 31 in A flat major Op. 110; Sonata No. 21 in C major Op. 53 “Waldstein”.

1993, November 2. Casals, Prélude; Bach, Toccata in E minor BWV 914; Mozart, Sonata in G Major K. 283; Medtner, Sonata in G minor Op. 22; Beethoven, Sonata No. 21 in C major Op. 53 “Waldstein”. (Tribute to Pablo Casals on the 20th anniversary of his death).

Recital at the Salle Gaveau

1996, February 2. Mozart, Fantasy in D minor K. 397 & Sonata in D Major K. 576; Beethoven, Sonata No. 21 in C major Op. 53; “Waldstein”; Dutilleux, Prélude “Le jeu des contraires”; Debussy 2 Préludes (La Fille aux cheveux de lin; “General Lavine” – Excentric); Chopin Nocturne Op. 15 No. 1; Impromptu No. 3 Op. 51; Scherzo No. 1 in B minor, Op. 20.

Music

Three outstanding Beethoven performances in France, at various times, venues and circumstances.

Beethoven, Concerto No. 3 in C minor Op.37. Eugene Istomin. Orchestre Philharmonique de l’ORTF, Ottavio Ziino. Live recording on December 19, 1967.

Audio Player.

Beethoven, Sonata No. 31 in A flat major, Op. 110. Eugene Istomin. Live recording at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées on October 30, 1991.

Audio Player.

Beethoven. Trio in B flat major Op. 97 “Archduke”, first movement (Allegro moderato). Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern, Mstislav Rostropovich. Live recording in Evian on May 22, 1990.

Audio Player