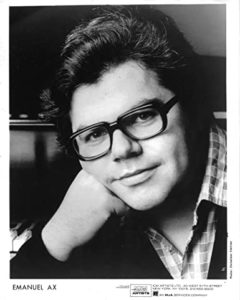

Istomin had a very high regard for Emanuel Ax. He disliked to taking part in juries, and rarely accepted, but he happened to be on the jury at the Queen Elisabeth Competition in 1972, where he was very disappointed that Ax placed only seventh, and the Arthur Rubinstein Competition in 1974, where he was delighted that he won First Prize. Istomin felt close to his younger colleague who was forging his career with the same ideals and passion. Ax too, wanted to be acknowledged as a great interpreter of both Beethoven and Chopin, Schumann and Ravel, Mozart and Rachmaninoff. He intended to be both a soloist and a chamber musician. Thanks to the changing times and to Istomin’s pioneering work, Emanuel Ax managed to overcome the old prejudices and build a very successful career, which was a source of great satisfaction for his elder. They also shared other interests like French language and culture, and sports.

Istomin had a very high regard for Emanuel Ax. He disliked to taking part in juries, and rarely accepted, but he happened to be on the jury at the Queen Elisabeth Competition in 1972, where he was very disappointed that Ax placed only seventh, and the Arthur Rubinstein Competition in 1974, where he was delighted that he won First Prize. Istomin felt close to his younger colleague who was forging his career with the same ideals and passion. Ax too, wanted to be acknowledged as a great interpreter of both Beethoven and Chopin, Schumann and Ravel, Mozart and Rachmaninoff. He intended to be both a soloist and a chamber musician. Thanks to the changing times and to Istomin’s pioneering work, Emanuel Ax managed to overcome the old prejudices and build a very successful career, which was a source of great satisfaction for his elder. They also shared other interests like French language and culture, and sports.

Seeing Emanuel Ax record Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances with Yefim Bronfman, who had also been one of his disciples, would have surely delighted Eugene Istomin.

Here are the memories of Emanuel Ax as recounted in a letter he wrote for the celebration of Istomin’s 75th birthday.

“I first saw Eugene Istomin when I was 13 years old. I was taken by some wonderfully patient people to the Marlboro Music Festival, where he was a visiting artist, already world-famous. I remember two things about those couple of days – he practiced with enormous dedication and concentration, and cooked an Indian meal that everyone exclaimed over (I was really too young to appreciate anything beyond French fries). After that initial experience I heard him countless times during my years as a student, he played regularly at Carnegie Hall as orchestral soloist, recitalist, and as a member of the stellar Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio. .

“I first saw Eugene Istomin when I was 13 years old. I was taken by some wonderfully patient people to the Marlboro Music Festival, where he was a visiting artist, already world-famous. I remember two things about those couple of days – he practiced with enormous dedication and concentration, and cooked an Indian meal that everyone exclaimed over (I was really too young to appreciate anything beyond French fries). After that initial experience I heard him countless times during my years as a student, he played regularly at Carnegie Hall as orchestral soloist, recitalist, and as a member of the stellar Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio. .

The next time we met was after a piano competition in Israel, in which I had the good fortune to do well – Mr. Istomin was a member of the jury. In what I came to know as his typically no-nonsense way, he congratulated me and at the same time made me aware of the amount of hard work and thought that I needed to put in, if I was to become what he called an ”official YAP – Young American Pianist”. I immediately took advantage of the opportunity and asked for piano lessons, and he just as quickly agreed. On my return to New York, I called and was told to come to his apartment on Central Park West – but not before the last inning of the Detroit Tiger baseball game. Whenever I arrived for our sessions a little early, I just waited until the game was over.

The next time we met was after a piano competition in Israel, in which I had the good fortune to do well – Mr. Istomin was a member of the jury. In what I came to know as his typically no-nonsense way, he congratulated me and at the same time made me aware of the amount of hard work and thought that I needed to put in, if I was to become what he called an ”official YAP – Young American Pianist”. I immediately took advantage of the opportunity and asked for piano lessons, and he just as quickly agreed. On my return to New York, I called and was told to come to his apartment on Central Park West – but not before the last inning of the Detroit Tiger baseball game. Whenever I arrived for our sessions a little early, I just waited until the game was over.

Those lessons are always with me – so much of what I feel about the music of Beethoven come from his illuminating words about the Waldstein Sonata, which I played for him. He was completely devoted to the printed score, but his imagination was not fettered by the score – rather, it was stimulated to even greater heights. This, I believe, is the true greatness of the creative artist – the ability to create a great interpretation by using the score as a guide, not a hindrance. Istomin exemplified this attitude, and through it he created magnificent interpretations of music from Beethoven and Bach to Chopin and Rachmaninoff.

He was so precocious as to be virtually a child prodigy – he won the revered Leventritt Competition and made his debuts with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra at the ripe age of seventeen – but his artistic path was always of the utmost seriousness and devotion. I was privileged to know him better in the ensuing years, and to enjoy his wide-ranging conversation and pointed sense of humor, but I never quite got over the awe that I had felt when I saw him on the stage of Carnegie Hall all those years ago. His artistry and words of wisdom are parts of the life of so many of his colleagues, and he will always remain in the annals of great pianists.”

He was so precocious as to be virtually a child prodigy – he won the revered Leventritt Competition and made his debuts with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra at the ripe age of seventeen – but his artistic path was always of the utmost seriousness and devotion. I was privileged to know him better in the ensuing years, and to enjoy his wide-ranging conversation and pointed sense of humor, but I never quite got over the awe that I had felt when I saw him on the stage of Carnegie Hall all those years ago. His artistry and words of wisdom are parts of the life of so many of his colleagues, and he will always remain in the annals of great pianists.”

In Pianist, James Gollin’s biography of Eugene Istomin, we can read this funny anecdote. One day, Emanuel Ax was in a hotel elevator and heard the famous cadenza of the first movement of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 5. The performance was so fantastic that he moved heaven and earth to find out who was playing! It was Eugene Istomin in the famous recording made in Prades with Casals in 1950.

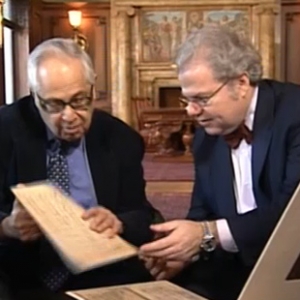

Naturally, Emanuel Ax participated in the Great Conversations in Music hosted by Eugene Istomin at the Library of Congress.

Document

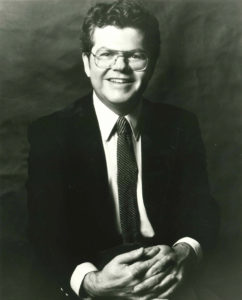

Emanuel Ax teaching Beethoven in his turn…

.

Emanuel Ax talking with Yannick Nézet Seguin