For Eugene Istomin, the 1950s were a time of irresistible, almost linear rise, which ended with the recording of Schumann’s Concerto with Bruno Walter in January 1960. Walter had never agreed to record piano concertos, except for the Beethoven Emperor Concerto, which he recorded twice (in 1934 with Gieseking and in 1941 with Serkin). This collaboration with Bruno Walter was a considerable honor, which proved that Istomin now belonged to the restricted circle of the very great pianists.

Many musicians, contrary to what history would later reveal, had feared that Istomin’s rise would be slow. William Steinberg accompanied him for the first time in December 1950. He then wrote to Mrs. Leventritt that this experience had been a “real and pure joy” but went on to mention that his seriousness and his refusal to include spectacular effects could make it difficult for the young pianist: “It will take him ten years more to hold on to his energy and perseverance until he finally reaches the top… His friends must help him because he is no type for managers.” Steinberg could have added that Istomin also was no type for critics! His recital at Carnegie Hall, a few weeks later, got a tremendous reception from the audience, but New York Times critic Harold Schonberg was very condescending, only admitting that “he certainly has the potentialities for first rate pianism.”

The 1951 Perpignan Festival witnessed a change in status for Istomin. The previous year, in Prades, he had only been given two works for solo piano and a brief trio sonata. This time, he played a Mozart concerto and gave two chamber music concerts with Schneider and Casals. Howard Taubman, the New York Times‘ correspondent, was very laudatory: “His growth in the past few years, as proved by his share in the evenings of Beethoven trios and his work as a soloist in Mozart’s E flat Concerto K. 449 has been astonishing… he is on the way to becoming one of our major pianists”.

.

The conquest of the great American orchestras was gradual. During the season 1951-52, he was invited by twelve North American orchestras and toured with two of them (Toronto and Buffalo). Long-lasting collaborations were already established with important conductors such as Paul Paray, William Steinberg, George Szell and Fritz Reiner. From that season forward, there were also Josef Krips, Pierre Monteux, Rafael Kubelik and Erich Leinsdorf. Ormandy, who had been giving a priority to Kapell for a long time, now invited Istomin almost every year. Munch was the last major musical director who still seemed reluctant, but their first association at Tanglewood in August 1955 was so successful that it launched the beginning of a warm friendship.

1955 marked a new turning point for Istomin. The Ravinia Festival, anxious to recreate the great event known as the “Million Dollar” Trio concerts with Rubinstein, Heifetz and Piatigorsky in 1949, decided to spotlight three young soloists on their way to becoming stars: Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose. Istomin played two concertos with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Enrique Jorda, and gave four chamber music concerts with Stern and Rose. The event made headlines and brought a great deal of publicity, but the main shift for this key year was the true beginning of Istomin’s recording career. Until then, nearly all of his discography was related to Casals (seven trios by Beethoven and Schubert, Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg and the Mozart Concerto K. 449) or to Busch (the Bach Concerto BWV 1052). The only recording Columbia had asked him for was Brahms’ Handel Variations in 1951.

1955 marked a new turning point for Istomin. The Ravinia Festival, anxious to recreate the great event known as the “Million Dollar” Trio concerts with Rubinstein, Heifetz and Piatigorsky in 1949, decided to spotlight three young soloists on their way to becoming stars: Eugene Istomin, Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose. Istomin played two concertos with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Enrique Jorda, and gave four chamber music concerts with Stern and Rose. The event made headlines and brought a great deal of publicity, but the main shift for this key year was the true beginning of Istomin’s recording career. Until then, nearly all of his discography was related to Casals (seven trios by Beethoven and Schubert, Bach’s Fifth Brandenburg and the Mozart Concerto K. 449) or to Busch (the Bach Concerto BWV 1052). The only recording Columbia had asked him for was Brahms’ Handel Variations in 1951.

The arrival of a true musician at the head of Columbia’s Artists and Repertoire Department, David Oppenheim, completely changed the situation. Oppenheim decided to launch an ambitious and coherent policy which covered a large and diverse repertoire, including modern works which Columbia had previously ignored. As for the piano, Oppenheim attributed a priority domain to each of the major Columbia pianists: Beethoven and the Germanic Romantic composers for Serkin, Mozart and French music for Casadesus, Chopin and the Russian repertoire for Istomin. This was the general project for developing Columbia’s repertoire, but Oppenheim was always open-minded to any suggestions from his artists. For Istomin, it was an exciting challenge, and one that would give a big boost to his career.

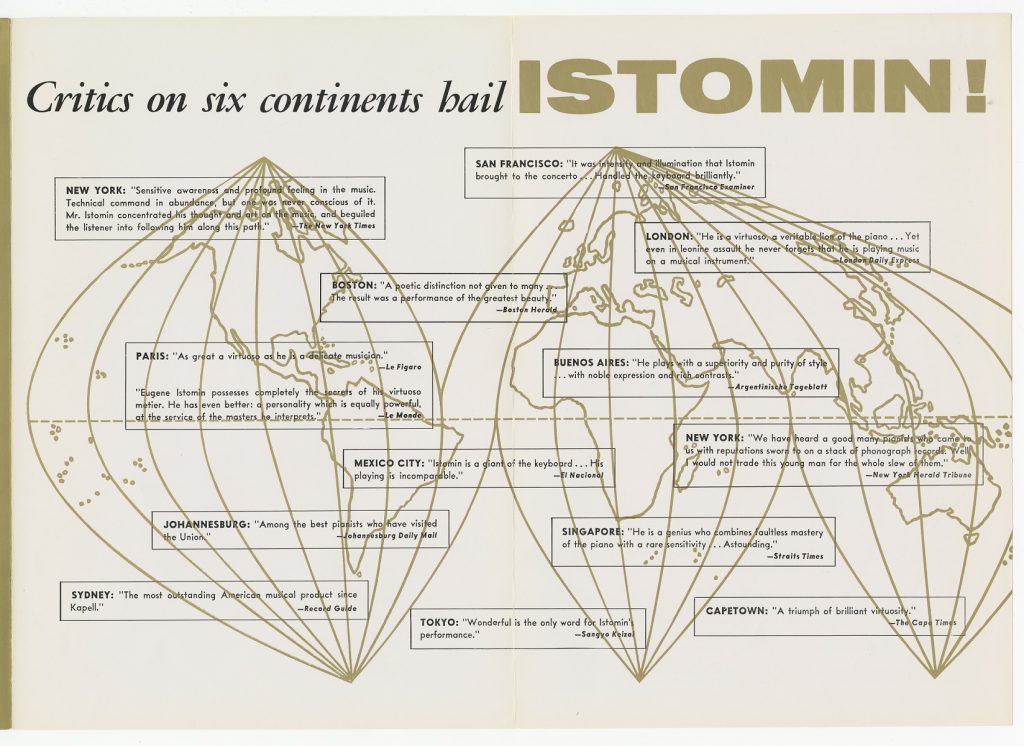

Internationally, Istomin was also progressing. His first long-distance tour, in the spring of 1955, was to South America, to which he returned two years later. In the autumn, he spent almost two months in South Africa and was immediately invited back. 1956 was just one continuous tour around the world, with fifty concerts in the Far East between April and June. He was forced to interrupt a series of forty-four concerts in Australia in early fall due to exhaustion. At that time, Europe was only a small part of his agenda. Strangely enough, France did not offer him any concerts outside the Prades Festival, and the Benelux only opened its doors in 1957. However, Italy and Switzerland had invited him regularly since 1950 and he was warmly received in England, which awarded him the Harriet Cohen Prize for the best recital of the season.

This intense activity could not fail to draw attention to Istomin, especially since critics were now almost unanimously praising his exceptional talent and early maturity. After his performance of Beethoven’s Fourth with the New York Philharmonic and George Szell, Paul-Henri Lang said in the New York Herald Tribune: “Of late we have heard of a good many pianists who come to us with enormous reputations. Well, I wouldn’t trade this young man for  the full slew of them.” The release in March and May 1956 of the two recordings he had just achieved for Columbia, the complete Nocturnes by Chopin and the Second Concerto by Rachmaninoff, was acclaimed by the entire press. High Fidelity Magazine spoke of the Rachmaninoff in ecstatic terms: dazzling, truly amazing, fiery technique… Istomin was better known as a specialist of Beethoven and Brahms, and now he was asserting himself as an exceptional performer of Rachmaninoff. It was a revelation!

the full slew of them.” The release in March and May 1956 of the two recordings he had just achieved for Columbia, the complete Nocturnes by Chopin and the Second Concerto by Rachmaninoff, was acclaimed by the entire press. High Fidelity Magazine spoke of the Rachmaninoff in ecstatic terms: dazzling, truly amazing, fiery technique… Istomin was better known as a specialist of Beethoven and Brahms, and now he was asserting himself as an exceptional performer of Rachmaninoff. It was a revelation!

Columbia decided to put its entire sales force at the service of Istomin. Its newsletter proclaimed: “Eugene Istomin is a great artist and he is growing greater every day. He is cast in the great tradition that gave us Rachmaninoff, Rubinstein, Horowitz and Serkin. He is unique in that it combines the virtuosity of a Rubinstein and a Horowitz with the incomparable musicality of a Serkin or a Rachmaninoff.” The disc became a best-seller, with the first pressing of seventy thousand copies selling out rapidly. Sales finally exceeded 200,000 copies.

The press took a close interest in Istomin. Time Magazine offered a stunning portrait on August 6, 1956. Under the title Music Ambassador, it echoed the very positive results of his long tour of the Far East under the aegis of the State Department. The following year, he was on the cover of Musical America and the article was entitled: The World At His Fingertips. Still more surprising was Kenneth McCormick’s initiative. The famous editor-in-chief of Doubleday insisted that Istomin write his autobiography, although he had just reached his thirties! Aware that Istomin did not have time to write himself, McCormick gave him a tape machine to record his story between two concerts, but Istomin would soon give up on this extravagant project.

The late 1950s confirmed his rise. He was now a frequent and privileged guest of the major American orchestras and toured with a European orchestra for the first time in 1959. He was able to realize his long-cherished dream of playing under Mitropoulos and collaborated for the first time with Bernstein, recently appointed music director of the New York Philharmonic. He continued to enrich his discography with the Brahms Intermezzi Op. 117, Mozart’s Quartet K. 493 and a series of great concertos: the Beethoven Emperor and the Chopin Second with Ormandy, and shortly after, the Schumann Concerto with Bruno Walter. He was even asked to record the Tchaikovsky First Concerto to compete with Van Cliburn’s disc, which was breaking all sales records. These brilliant developments did not prevent him from remaining faithful to those who had believed in him and had contributed to launching his career. He had reconnected with Casals and came to the Puerto Rico Festival every year. From 1957 to 1959, he spent a part of each summer in Marlboro, the ideal place for talented young musicians conceived by Busch and Serkin.

During this decade, which made him famous, Istomin underwent various trials which also brought him maturity on a human level. The first three years with Casals had been infinitely enriching, even euphoric, but the 1952 Festival ended in a somewhat tense atmosphere. Schneider, who was upset by difficulties with the French Committee and engaged in a new love affair with Geraldine Page, announced that he was giving up the responsibility of organizing the festival. As Istomin was so close to Casals, it was natural that he take over. It was an enormous responsibility, even though he could rely on Madeline Foley for help. It was necessary to assemble a new orchestra with mainly American musicians, choose and hire the soloists, construct the programs and find sponsors, negotiate the agreements with Columbia and the French Radio, all the while remaining constantly in touch with Casals.

The 1953 festival was a great success, but there were many difficult moments. The festival left a significant deficit due to the high cost of the orchestra. Istomin faced up to his responsibilities and learned a great deal from this experience. In 1954, in order to restore the financial situation, Istomin planned a very different, much simpler and cheaper festival. The musical ambition was not diminished, but there were only eight concerts and six musicians to perform Beethoven’s complete chamber music with piano. Istomin hoped to be able to initiate more ambitious projects again for the following summers, especially for Mozart’s bicentennial, but the adventure ended in 1955 after a violent dispute with Casals, whose pride had been injured. The conflict did not last, but was difficult to live through, with the realization that even the greatest of men can experience moments of weakness.

Another dramatic event had deeply affected Istomin: the death at the age of thirty-one of his friend William Kapell. Aside from the deep sadness and sense of injustice, it was the loss of an alter ego and of the only person who could question him and goad him into being ever more self-demanding.

For Istomin, the 1950s were an incredibly rich and fruitful period, and brought him close to the summit. These were also years of continual challenge and whirlwind activity. For two years, Casals and the Prades Festival often diverted him from his piano. From 1955 onwards, he often let himself become intoxicated by the accumulation of concerts (one hundred and fifty in 1956) and trips around the world. One of the most regrettable consequences was that he could not find time to expand his repertoire. Nearly all the new works he learned at that time were related to his recording schedule. The development of his career owed a lot to the disc, and especially to David Oppenheim, but in the spring of 1959, bad news surfaced: Oppenheim, tired of having to fight against the directives of a short-sighted management, resigned. Istomin was saddened, but as yet could not imagine what consequences this would have on his career.

For Istomin, the 1950s were an incredibly rich and fruitful period, and brought him close to the summit. These were also years of continual challenge and whirlwind activity. For two years, Casals and the Prades Festival often diverted him from his piano. From 1955 onwards, he often let himself become intoxicated by the accumulation of concerts (one hundred and fifty in 1956) and trips around the world. One of the most regrettable consequences was that he could not find time to expand his repertoire. Nearly all the new works he learned at that time were related to his recording schedule. The development of his career owed a lot to the disc, and especially to David Oppenheim, but in the spring of 1959, bad news surfaced: Oppenheim, tired of having to fight against the directives of a short-sighted management, resigned. Istomin was saddened, but as yet could not imagine what consequences this would have on his career.

Music

Brahms. Handel Variations Op. 24, Theme and Variations I to VI. Eugene Istomin. Recorded for Columbia in March 1951.

Audio Player.

Beethoven. Trio in G major Op. 1 No. 2, two last movements (Scherzo, Allegro; Finale, Presto). Eugene Istomin, Joseph Fuchs, Pablo Casals. Live recording on June 7, 1954.

Audio Player.

Rachmaninoff. Concerto No. 2 in C minor Op. 18, first movement. Eugene Istomin, Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy. Recorded for Columbia on April 8, 1956.

Audio Player.

Chopin, Nocturne No. 13 in C minor Op. 48 No. 1. Recorded for Columbia on September 21, 1955

Audio Player