Istomin’s relationship with Columbia, which was his record company for forty years, was often conflictual. Obviously, apart from a few rare and brief periods, Columbia’s policy suffered from a huge lack of artistic ambition. The dictates of short-sighted marketing most often outweighed musical considerations. In the 1970s, the firm ultimately discouraged even its most loyal and prestigious artists, losing Bernstein, Horowitz and Serkin in succession.

Istomin’s collaboration with Columbia can be summarized as follows: an early start but without follow-up in the mid-1940s; a rich and intense decade in the 1950s; a very chaotic progression in the 1960s; a spectacular break-up in 1970; and a few extra recordings in the late 70s and early 80s.

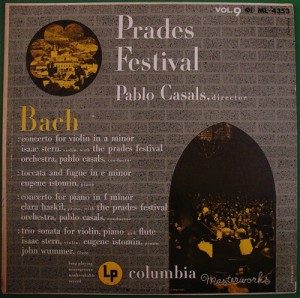

Istomin recorded Bach’s Concerto in D minor BWV 1052 under the direction of Adolf Busch in April 1945. He was nineteen years old, an unusually early age to start a recording career. This was not really Columbia’s wish, but Busch had insisted that the young pianist be part of the recording schedule of the Busch Chamber Players. In the next five years, Istomin did not receive any proposals from Columbia. He had to wait for the Prades Festival in 1950, where every work which was performed in concert, with the exception of the Suites for solo cello and the cantatas, was scheduled to be recorded. Serkin had renounced recording the Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 out of loyalty to Adolf Busch, his mentor and father-in-law, with whom he had recorded the work in 1935. Istomin stepped in for him and learned the work, with its vertiginous cadenza, within a few days. The recording went well, as did that of the Trio Sonata BWV 1038 with Stern and Wummer. The HMV studio truck left Prades immediately after the festival and Istomin had to go to London a few weeks later to record the Toccata BWV 914 and the Partita BWV 826 (which he refused to let be released).

Istomin recorded Bach’s Concerto in D minor BWV 1052 under the direction of Adolf Busch in April 1945. He was nineteen years old, an unusually early age to start a recording career. This was not really Columbia’s wish, but Busch had insisted that the young pianist be part of the recording schedule of the Busch Chamber Players. In the next five years, Istomin did not receive any proposals from Columbia. He had to wait for the Prades Festival in 1950, where every work which was performed in concert, with the exception of the Suites for solo cello and the cantatas, was scheduled to be recorded. Serkin had renounced recording the Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 out of loyalty to Adolf Busch, his mentor and father-in-law, with whom he had recorded the work in 1935. Istomin stepped in for him and learned the work, with its vertiginous cadenza, within a few days. The recording went well, as did that of the Trio Sonata BWV 1038 with Stern and Wummer. The HMV studio truck left Prades immediately after the festival and Istomin had to go to London a few weeks later to record the Toccata BWV 914 and the Partita BWV 826 (which he refused to let be released).

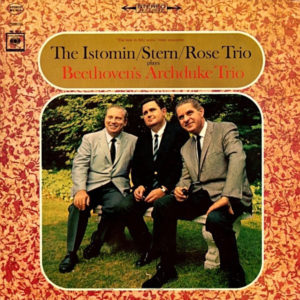

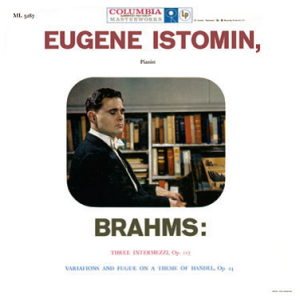

After Prades, his reputation having been enhanced by his participation in the prestigious festival and by Casals’ support, Istomin received an offer by Columbia to record the Brahms Variations on a Theme by Handel in March 1951. A few months later, the Perpignan Festival expanded his discography in a spectacular manner: Mozart’s Concerto in E flat major K. 449, four Beethoven trios (Op. 1 No. 2, Op. 11, Op. 70 No. 2 and Op. 97, “Archduke”) and the Schubert Trio in B flat major D. 898. One would have thought that Columbia would give its full support to such a promising young artist, but this was not the case. In the next three years, Istomin recorded again exclusively with Casals at the Prades Festival. In 1952, two works by Brahms (Cello Sonata No. 1 and Trio No. 3) were not approved by Casals and remained unreleased. In 1953, there were two Beethoven trios with Joseph Fuchs replacing Schneider (Op. 1 No. 1 and Op. 70 No. 1) and two short encores (Bach and Falla). .

After Prades, his reputation having been enhanced by his participation in the prestigious festival and by Casals’ support, Istomin received an offer by Columbia to record the Brahms Variations on a Theme by Handel in March 1951. A few months later, the Perpignan Festival expanded his discography in a spectacular manner: Mozart’s Concerto in E flat major K. 449, four Beethoven trios (Op. 1 No. 2, Op. 11, Op. 70 No. 2 and Op. 97, “Archduke”) and the Schubert Trio in B flat major D. 898. One would have thought that Columbia would give its full support to such a promising young artist, but this was not the case. In the next three years, Istomin recorded again exclusively with Casals at the Prades Festival. In 1952, two works by Brahms (Cello Sonata No. 1 and Trio No. 3) were not approved by Casals and remained unreleased. In 1953, there were two Beethoven trios with Joseph Fuchs replacing Schneider (Op. 1 No. 1 and Op. 70 No. 1) and two short encores (Bach and Falla). .

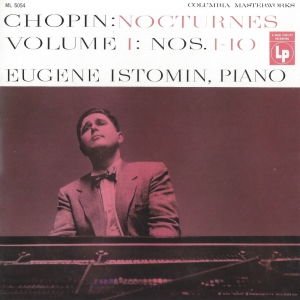

The appointment of David Oppenheim as director of Artists and Repertoire in 1954 gave a remarkable boost to Columbia’s classical department. Oppenheim tried to expand the catalogue, (particularly in regard to modern music), hire new instrumentalists and conductors such as Gould and Bernstein, and make better use of the talents who were already under contract. In the piano repertoire, Robert Casadesus was entrusted with Mozart and French music, Rudolf Serkin with the great Germanic repertoire, and Istomin with Chopin and the Russian repertoire. It was the true start of Istomin’s recording career, with two significant projects: the complete Nocturnes by Chopin (throughout 1955) and Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto (in April 1956).

The appointment of David Oppenheim as director of Artists and Repertoire in 1954 gave a remarkable boost to Columbia’s classical department. Oppenheim tried to expand the catalogue, (particularly in regard to modern music), hire new instrumentalists and conductors such as Gould and Bernstein, and make better use of the talents who were already under contract. In the piano repertoire, Robert Casadesus was entrusted with Mozart and French music, Rudolf Serkin with the great Germanic repertoire, and Istomin with Chopin and the Russian repertoire. It was the true start of Istomin’s recording career, with two significant projects: the complete Nocturnes by Chopin (throughout 1955) and Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto (in April 1956).

The Chopin Nocturnes were warmly received by the critics, but for Rachmaninoff, the reception was rapturous. The leading American music magazine, High Fidelity, did not skimp on its praise: “dazzling”, “truly stunning”, “technique to burn”. The record became a best-seller. The 70,000 copies of the first pressing sold out within a few weeks. In total, sales reached 200,000 copies, an exceptional figure for classical music.

Columbia’s commercial staff mobilized its forces in order to promote Eugene Istomin and his recordings. The internal newsletter of June 7, 1956 proudly stated: “Eugene Istomin is a great artist, and is growing greater every day. He is cast in the great tradition that gave us Rachmaninoff, Rubinstein, Horowitz and Serkin.” The salespeople were exhorted to ever greater heights: “Don’t just sell the repertoire and the sound, sell Istomin! Elsewhere in this issue we’ve given you the most sensational sales story we’ve ever had on a single masterworks artist since Oistrakh!” (…) Sell Istomin! We’re going all out to make him our big Romantic pianist who will give us the kind of warhorse concerti our catalog has needed.” The Rachmaninoff record was promoted at a very affordable price ($2.98) as “Buy of the Month” in June, then as “Record of the Month” in October.

This focus on Chopin and Rachmaninoff did not mean that other repertoire was forbidden. In the spring of 1957, Istomin was due to record Mozart’s Concerto K. 271 and the Schubert Trio in B flat major with Casals in Puerto Rico, but Casals’ heart attack disrupted the program and Istomin only joined Stern, Katims and Mischa Schneider in Mozart’s Piano Quartet K. 493. He recorded the Brahms Intermezzi Op. 117 in September 1957, (to allow his Handel Variations to be re-issued on a 12-inch LP) and the Beethoven Emperor Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy in January of 1958.

Meanwhile, David Oppenheim was growing tired of being forced to record the same works over and over again, as any plans to expand the repertoire were constantly resisted by both the general management and the marketing department. Goddard Lieberson, the president of Columbia, had been the artistic director of Istomin’s first record in 1945. By the end of the 1940s, he had understood the interest of the microgroove records, especially for classical music, and made a major contribution to its development, but in the mid-1950s, he still did not believe in the future of stereo! Columbia did not record in stereo until 1958, whereas RCA, Mercury and Decca had already started in 1955. As time passed, Lieberson, despite his solid training as a classical musician, became increasingly involved in musicals and limited the recordings of classical music to the most profitable repertoire. Discouraged, Oppenheim finally resigned in 1959. Goddard Lieberson called upon Schuyler Chapin to replace him, and this decision proved to be disastrous for Istomin’s recording career. .

James Gollin told the story of this episode in his biography of Istomin. Schuyler Chapin had previously worked for NBC and for Columbia Artists Management. He had accompanied Jascha Heifetz on his tours throughout the United States for many years, and Istomin was on very friendly terms with him. It so happened that the Philadelphia Orchestra’s manager, Donald Engle, had just resigned. Chapin applied for the position, and knowing that Istomin was very close to Ormandy, asked him to intervene on his behalf. Istomin carried out this mission, but was told by Ormandy that it was out of the question because, according to him, Chapin was only “good at wearing coats” for Lily Pons or Jascha Heifetz. It was a difficult reason to relay! Istomin was evasive about Ormandy’s answer and tried to convince his friend to pursue a career in television, but Chapin strongly felt that Istomin had not wanted to support him and subsequently harbored a great deal of resentment towards him.

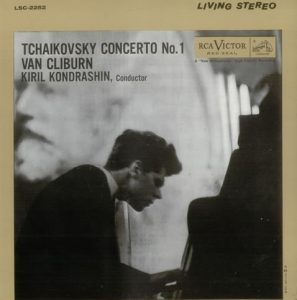

In the fall of 1958, RCA published a recording of the Tchaikovsky Concerto No. 1 with Van Cliburn, just after his highly mediatized triumph at the Tchaikovsky Competition. RCA had launched an unprecedented advertising campaign, so this record promised to break all sales records. Columbia’s management decided that it was imperative to react by releasing a record capable of competing with RCA. To this end, Istomin was duly asked to record the Tchaikovsky Concerto, in the hope that he would repeat the huge success of his Rachmaninoff Second. He was forced to learn and record the concerto after only a single concert. The reviews were positive, but the commercial result was considered by Columbia to be disappointing. It must be said that there was no publicity. Perhaps Lieberson and his marketing team thought that it was pointless to promote Istomin, since RCA was in the process of saturating the market. Van Cliburn’s record reached the astronomical figure of a million sold copies, and Columbia realized that it had made a serious strategic mistake. .

Istomin was proud of his recording and felt that he had fulfilled his mission. He felt that he was in fact a victim of the inconsistency of Columbia’s policy, and made an appointment with Goddard Lieberson, not only to discuss the renewal of his contract, but mainly to complain about the lack of support for his recordings in general, and of the Tchaikovsky in particular. Istomin was all the more disconcerted, as his Rachmaninoff had been so successfully promoted by Columbia. He was still offered very expensive recordings with prestigious partners like the Philadelphia Orchestra, Ormandy, and Walter – but there was no longer any real attempt at promotion, other than a few pages in the concert programs – and nothing in the press. Schuyler Chapin attended the meeting and was extremely hostile, even going so far as to imply that the chords at the beginning of the Tchaikovsky Concerto did not sound as spectacular as they should have! He suggested that Istomin take charge of his own promotion. The discussion remained very tense throughout lunch. A few days later, Istomin learned that his contract was suspended and that all projects had been cancelled, including the stereo re-recording of Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto which was scheduled for April 1961 and a nearly completed disc of Beethoven sonatas.

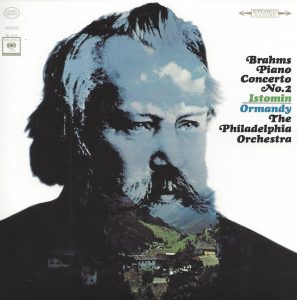

During the four years of Chapin’s tenure at Columbia, Istomin did not once enter the Columbia studios, but when Chaplin left in late 1963 after being appointed vice-president of the Lincoln Center, he made seven records for the company in the three next years! However, this did not mean that his relationship with Columbia had returned to its former idyllic conditions. He felt that he had been betrayed by Lieberson, who was to remain as manager of the company until 1975. The former sense of mutual trust was irrevocably broken. Columbia offered him new contracts, mainly because of the Trio he had founded with two other Columbia exclusive artists, Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose. The concerts and recordings of this trio had a considerable impact all over the world. In order to retain the privilege of publishing the trio’s records, and to prevent Istomin from signing with another company, Columbia gave him the opportunity to make a few records as a soloist: Brahms’ Second Concerto in 1965, the Beethoven Fourth in 1968 (for the 25th anniversary of his debut), and the Schubert Sonata in D Major D. 850 in 1969. A nearly completed disc of encores, together with the Stravinsky Sonata, was never released, and would be published only in 2015 by Sony.

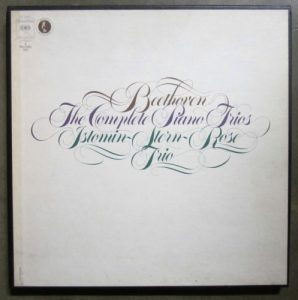

This ambiguous and somewhat perverse situation lasted until the early 1970s. For the bicentenary of Beethoven’s birth, Istomin, Stern and Rose had decided to perform the complete chamber music with piano in a series of eight concerts in Paris, London, Switzerland and New York. Columbia had initially planned to publish only the complete Trios. In April 1969, realizing the enthusiasm generated by this unprecedented challenge, the firm proposed that the three musicians also record the complete works for piano and violin and for piano and cello. For Istomin, this was a huge extra effort. Only two trios (the Archduke and Opus 1 No. 3) and the Kakadu Variations had been previously recorded. Istomin and his colleagues had planned to record five trios and three shorter works between May 1969 and May 1970. Considering Istomin’s busy concert schedule, to prepare, rehearse and record ten Violin Sonatas, the six Cello Sonatas (including Op. 17), and three sets of Variations all at the same time seemed like a Herculean task. Moreover, this accumulation of chamber music recordings could be detrimental to his reputation and career as a soloist. .

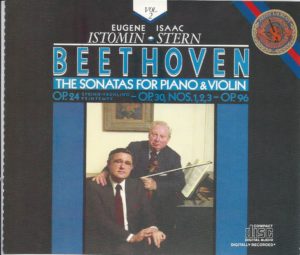

Istomin initially accepted, persuaded by the enthusiasm of his colleagues and friends and spurred on by the musical challenge. A total of four sonatas – No. 1 and No. 7 for violin; No. 3 and No. 5 for cello – were recorded in the summer of 1969. However, Istomin asked Columbia to make him a reasonable proposal in order to give additional luster to his image as a soloist by also recording concertos or solo works. At the very least, he wanted to record the Emperor Concerto again, as the 1958 LP had disappeared from the catalogue (it was published only in mono, since the stereo tape was defective). He even suggested the Beethoven Third, and possibly the complete cycle. Columbia promised to consider his proposal, but replied after a long delay that the overload on its studios and crews did not allow for any new project until 1971, and that they would re-evaluate the issue at a later date. Istomin was already aware that he was being manipulated by Columbia, but this time he found it was too much to endure. He decided to give up on recording the sonatas and to complete only the Trios. Isaac Stern was both disappointed and relieved, because he did not yet feel ready to record some of the sonatas which he had never played in concert. In addition to this, his extremely busy schedule gave him little time to work on them in such a short period. On the contrary, Leonard Rose was furious, because he regarded this recording as the crowning achievement of his career. This crisis could have been fatal to the Trio. After a difficult time, they resumed their friendship and the pleasure of playing together, but the sense of complicity would never be the same again.

Until Lieberson left in 1975, Istomin no longer set foot in Columbia’s studios! Between 1976 and 1979, he recorded only Mozart’s Trio K. 502 (the tapes were lost!) and the Mendelssohn Trio No. 2 which, according to him, was the highest achievement of the Trio’s discography. Thomas Frost had just taken over as Head of the Artists and Repertoire department and this led to hopes that a new collaboration could be launched. Frost, who had been the producer of all Casals’ recordings in Marlboro and most of Horowitz’s, admired Istomin, and was highly impressed by his culture and his in-depth knowledge of the scores. He was particularly amazed by the role Istomin played during the recording of Beethoven’s Triple Concerto: “He heard everything, including in the orchestra, and he knew exactly what he wanted. He even managed to share his convictions with the conductor (Ormandy) and the other two soloists (Stern and Rose).” Frost had also been Istomin’s producer for the Brahms Concerto No. 2 and the Beethoven Fourth. He decided to reissue some of Istomin’s recordings which had not been available for a long time. Concertos by Chopin, Schumann and Tchaikovsky were published in 1977 by the Odyssey Budget Collection. A co-production was planned with the Polish label Muza to record Szymanowski’s Symphonie Concertante in Warsaw under the direction of Jerzy Semkow, but this could not be implemented. Frost also wanted to expand Columbia’s repertoire. He suggested that Istomin embark on a complete recording of Scriabin’s works. Istomin liked Scriabin, but he had never performed his music and did not feel close enough to his universe to accept such a challenge. Instead, he suggested recording Rachmaninoff, in particular the Variations on a Theme by Chopin which he so loved – but unfortunately, Columbia had just entrusted Ruth Laredo with the complete recording of Rachmaninoff’s work. In the end, no agreement could be reached, despite the good will of both parts. It proved to be too difficult to rebuild relationships after such a definitive break-up.

Nevertheless, Istomin recorded again for Columbia, which was now CBS. He had finally given in to the pleas of his friend Isaac Stern to complete the recordings of the Beethoven Violin Sonatas which they had begun in 1969. Between November 1982 and December 1983, they recorded the eight missing Sonatas. Istomin refused to sign a contract and never received any royalties. He had not even wished to listen to the takes, and gave Isaac Stern a free hand in supervising the post-production.

Istomin’s resentment was also related to the use that Columbia, CBS and Sony (which had bought the company in 1988) made of his recordings. Only the trios with Isaac Stern and Leonard Rose were regularly reissued, but usually only in collections dedicated to Stern. Some of his recordings with Casals have been republished, also in collections dedicated to Casals. The only concerto that almost never left the catalogue was the Schumann, as Bruno Walter was conducting. In 1989, CBS UK managed to re-release his recording of the Tchaikovsky Concerto No. 1 without any coupling. How could a thirty-four minute CD be successful, even in a very cheap collection? How was it possible that the thought never occurred to anyone of coupling it with his recording of the Rachmaninoff Second, which remained a must for many piano lovers and had previously never been published before on CD? In 1991, Sony France announced a boxed set of all the Tchaikovsky concertos in the “Maestro Collection”, mentioning that the First Piano Concerto would be Istomin’s version – but Sony New York chose to send Gary Graffman’s recording instead! Many such anecdotes prove how little consideration Columbia and its successors had for Eugene Istomin. Oddly enough, the most significant re-releases were made in unexpected countries, like Argentina (where the Chopin and Schumann concertos were awarded “Record of the Year” a decade after being issued in the US) and, above all, Japan.

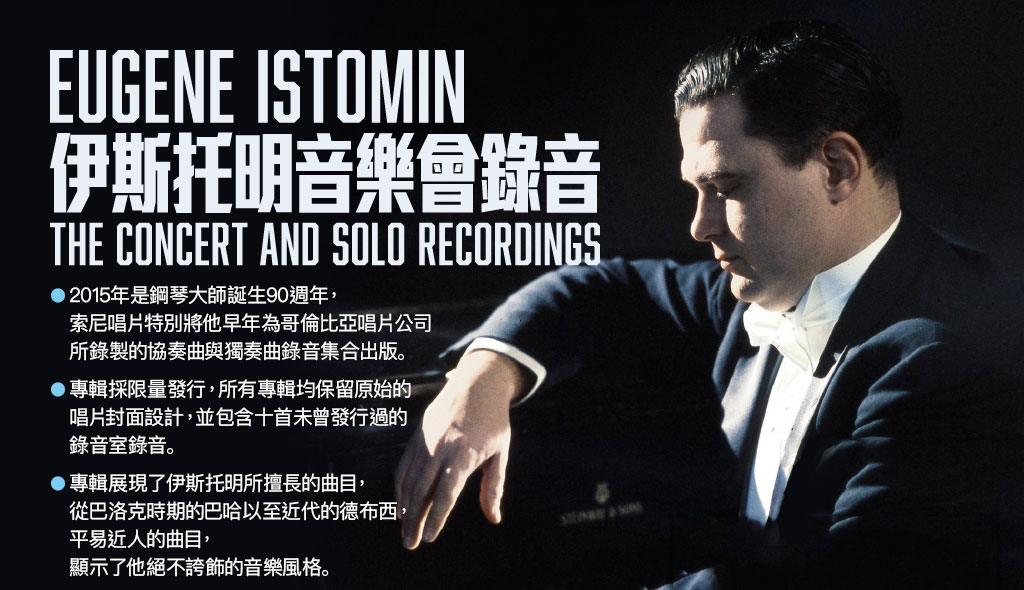

The break with Columbia in 1970 proved to be extremely damaging for the last three decades of Istomin’s career. At that time, the visibility and support which a record company provided was crucial. Of course, his recorded legacy is also much less than it should be. It was not until 2015 that Sony, thanks to Gary Graffman and Robert Russ, finally made it available by issuing a box of twelve CDs, carefully remastered, of all his concerto and solo piano recordings, including some precious unpublished material.

Music

Brahms. Intermezzo Op. 117 No. 1. Recorded by Columbia in 1957 when David Oppenheim was in charge of the A&R Department.

Audio Player.

Debussy. Clair de lune (from Suite Bergamasque). Recorded in 1968 for an encore LP which was not released, due to the clash with Columbia’s management. All of Istomin’s unpublished material was finally issued by Sony in 2015.

Audio Player.

.