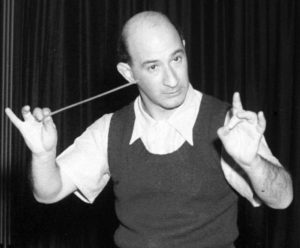

“He is no type for managers!” The prediction made by William Steinberg in December 1950 was amply proven. Istomin’s relationships with his managers were always tricky! To him, the managers embodied the mercantile aspect of music, often in a caricatural way. He changed managers several times, often out of frustration due to their inactivity or incompetence.

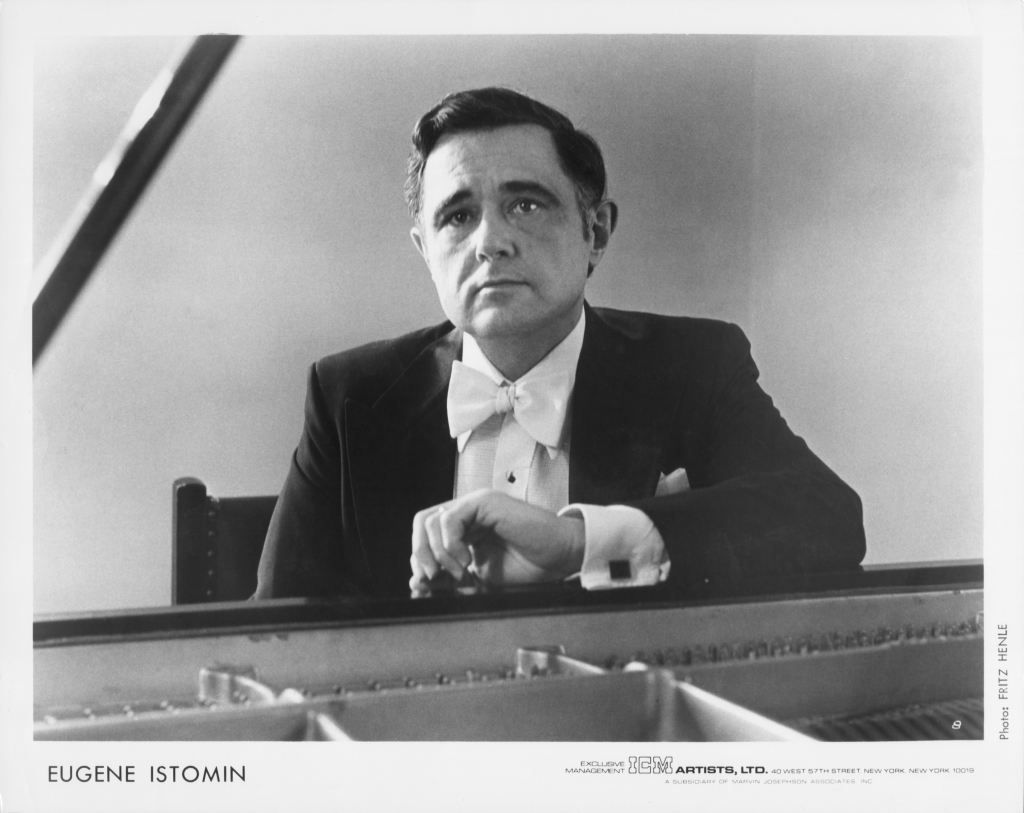

Istomin’s father had warned him repeatedly that if he were not more docile and cooperative with his managers, it could jeopardize his career. His friend Isaac Stern often lectured him about this matter, but Istomin always refused to compromise. He was nearly blacklisted by the Community Concerts for refusing to cut long works and program only popular pieces. He was unwilling to promote himself by posing for photos, engaging in public relations, or wooing journalists. When he granted an interview, he did nothing to highlight himself, and gave priority to providing honest opinions.

We can see a glimpse of Istomin’s thoughts about managers through Thornton Trapp’s comments in the diary he recorded during the Beethoven tour of 1970: “What manager deserves his percentage? They never want to sell the best artist, but the one who gets the biggest fee, however bad an artist may be. Why sell Horszowski when you can sell Van Cliburn? You’d be mad to turn down a thousand dollars for two hundred dollars in commissions! It’s astonishing that any of the Horszowskis can survive. Perhaps there are even some who don’t.” Istomin was not far from sharing the same opinion.

The years at CAMI (1943-1962)

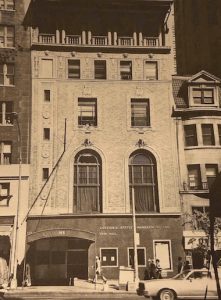

On the advice of Serkin and the Leventritt family, Istomin signed a contract very early on with CAMI (Columbia Artists Management Inc.). It was immediately after the two competitions he won in 1943, when he was just eighteen years old. At that time, CAMI was run by Arthur Judson, who ruled the American musical world by managing most of the great conductors. Judson was also General Director of the New York Philharmonic and, for a while, of both the Philadelphia and Cincinnati Orchestras! Today people would be screaming about a conflict of interest, but at the time it did not seem to shock anyone. Judson could make or break careers at will, and he had no qualms about doing so each time someone stood up to him. That is how he succeeded in driving a great conductor like Arthur Rodzinski out of America. A former violinist, he nevertheless respected music and knew how to recognize talent. He immediately warned Istomin that due to his choice of repertoire, he would need time to reach the top. He was already managing the careers of two great pianists, Rudolf Serkin and Robert Casadesus, and also that of a rising star who would soon become Istomin’s best friend – William Kapell. Judson was more supportive of Kapell, whom he considered to be more tractable and seductive in his attitude and repertoire. He guessed that Kapell would bring him more money, and much faster than Istomin.

Although his career was progressing, Istomin was impatient. There was a first conflict in 1945, when Istomin wanted to play under the direction of Dimitri Mitropoulos in Cincinnati and Judson refused. Istomin asked for a meeting and expressed his feeling of not being supported as his talent deserved. Judson replied that if he was not satisfied, he should look for another manager. Convinced that this would dampen the young pianist’s fighting spirit, he was amazed to hear Istomin tell him that this was exactly what he planned on doing! Serkin, despite his reluctance to take this type of action, was forced to intervene in order to salvage the situation. Istomin would remain with CAMI until 1962. CAMI played a positive role in Istomin’s rise. However, like his OYAP colleagues Graffman and Fleisher, he was finding it increasingly difficult to put up with the motherly patronizing of Ruth O’Neill and Ada Cooper, Judson’s two lieutenants. They justified not raising his fee by citing his youthful age, without realizing that he was approaching forty, and chastised him whenever he dared to ask for an advance on his fees, accusing him of squandering his money on the cinema! What led to his decision to leave CAMI was Stern’s proposition to join Hurok, as it was more convenient that all three members of the Trio be under the same management.

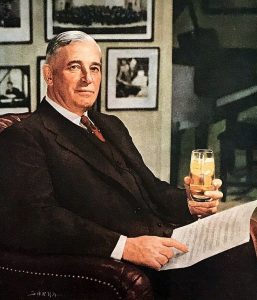

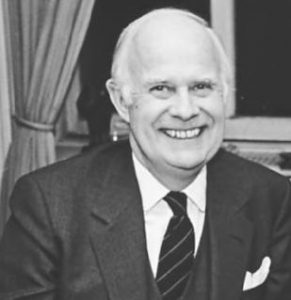

Sol Hurok (1962-1974)

Sol Hurok had built his reputation on a few big stars and on his special relationship with Soviet artists (he had succeeded in bringing the Bolshoi Ballet over in the middle of the Cold War). He had an amazing ability to use advertising and the press to highlight an artist or an event. This he did quite often, without scruples, and without asking the artist for his opinion. Thus, to his dismay, Serkin was presented for his American debut as a Russian pianist!

In 1943, Sol Hurok, who had just enlisted Isaac Stern, had expressed his desire to have Istomin on his roster, but Istomin did not want to be labelled as “Russian” and preferred CAMI. Twenty years later, Hurok confirmed his interest in him. This time, Istomin accepted, encouraged by Stern and impressed by the efficiency with which Hurok had launched the Istomin-Stern-Rose Trio in the United States. .

In fact, Istomin always felt uncomfortable in this company, which was focused on big events and media stunts. Music and art were of secondary importance. For Hurok, Istomin was above all the pianist of the Trio, and he did little to support his career as a soloist. It would have been more judicious to entrust his solo activity to CAMI and to depend on Hurok only for the Trio. Hurok, who organized the only tour of Istomin in the USSR in 1965, was aging. Moreover, he was being harassed by a far-right Jewish faction who was protesting vehemently against the invitation of Soviet artists to America. A bomb was placed in his offices which killed one of his secretaries and brought him close to asphyxiation. He died two years later, in 1974, at the age of eighty-two. .

The battle for his succession was merciless. Sheldon Gold, with whom Istomin was friendly, lost out. He was forced to move to CAMI but could not stay on there, and entered ICM. Istomin followed him throughout his successive changes. However, in the summer of 1976, Istomin was still hesitating about his definitive choice, and expressed his doubts to Rostropovich who was currently in Puerto Rico for the Casals Festival. Rostropovich advised him to stay at CAMI and entrust his management to Ronald Wilford, who was Judson’s worthy successor and who had established himself as the most powerful American manager. Rostropovich even interceded with Wilford, who confirmed his willingness to manage Istomin’s career. But Istomin had reservations about Wilford’s personality, which he considered to be more that of a businessman rather than a man of music, and he eventually favored loyalty to his friend Sheldon Gold. At ICM, Istomin did not find the support he needed at this stage in his career, when it was crucial to relaunch his collaborations with the major American orchestras, which Wilford probably could have accomplished. Thirty years later, Rostropovich was still convinced that Istomin had made an unfortunate decision.

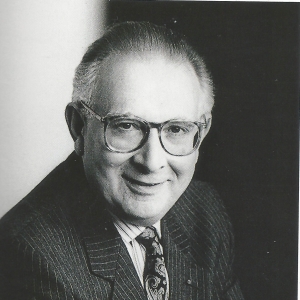

Harold Shaw

In 1987, ICM proved to be totally incapable of organizing the tours that Istomin planned throughout the United States, transporting his own pianos in a specially adapted truck. On the advice of his friend Peter Gravina, Istomin turned to Harold Shaw, who had worked for Hurok for many years before founding his own agency in 1969. Shaw had welcomed great musicians such as Vladimir Horowitz, Nathan Milstein, Henryk Szeryng, Jacqueline Du Pré and Jessye Norman, but he remained first and foremost a music lover. He was very friendly with Horowitz and was able to persuade him to return to the stage and perform on a regular basis from 1974 onwards.

In 1987, ICM proved to be totally incapable of organizing the tours that Istomin planned throughout the United States, transporting his own pianos in a specially adapted truck. On the advice of his friend Peter Gravina, Istomin turned to Harold Shaw, who had worked for Hurok for many years before founding his own agency in 1969. Shaw had welcomed great musicians such as Vladimir Horowitz, Nathan Milstein, Henryk Szeryng, Jacqueline Du Pré and Jessye Norman, but he remained first and foremost a music lover. He was very friendly with Horowitz and was able to persuade him to return to the stage and perform on a regular basis from 1974 onwards.

Shaw was excited by Istomin’s project and chose one of his best assistants, Martha Coleman, to set it up. She succeeded wonderfully, especially in the southeastern United States where she was born. Istomin had finally found the management he needed, and he remained loyal to Harold Shaw until Shaw’s retirement in 1996.

In Europe

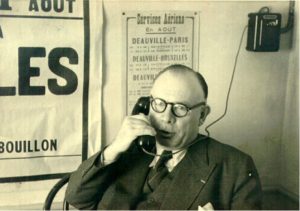

Istomin’s relationships with European managers were just as difficult as in the United States, if not more so! When he made his debut in Switzerland and Italy, Istomin had benefited from the contacts established by Casals and Serkin, and things had gone very well. In France, Paray had recommended him to the main Parisian impresario, Marcel de Valmalète, who agreed to manage his career in France and suggested that Istomin play in some fashionable salons to improve his notoriety. Istomin clearly rejected these practices from another time and Valmalète could not find any engagements for him. Tired of not seeing anything materialize, despite his important presence at the Prades Festival, he decided to join Isaac Stern at OAI, the office managed by Michael Rainer.

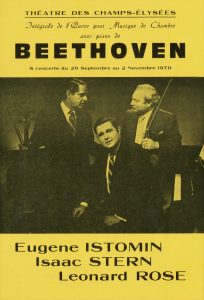

Rainer’s roster was very impressive (Rubinstein, Serkin, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Birgit Nilsson, Joan Sutherland…). However, Istomin soon had the feeling that Rainer worked very little for him and was content to merely receive his percentage from concerts which did not come from his own initiatives. Istomin’s resentment came to a head during the Beethoven year. Organizing the complete chamber music series at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées by the Trio Istomin-Stern-Rose was relatively simple for Rainer (eight concerts in a row!) and an extremely profitable operation, so Istomin thought he could ask OAI for a small favor – finding a room in Paris for a friend who came to attend the concerts. This turned out to be too much to ask. Here is Trapp’s report of the incident, which first led to a major dispute with Stern: “Rainer’s staff had left Mickey bed-less in Paris for one night, after being carefully briefed by Eugene. He was furious, and Isaac very little less so. He said that Eugene should not have asked Rainer’s staff to do the booking. Eugene said they did little but take the commission, so why shouldn’t they do a job for a change, etc, etc, etc.” But Stern definitely knew much better than Istomin how to deal with managers and ensure their dedication! The incident could have ended there, but there was another episode a couple of weeks later. Michael Rainer had organized a dinner at Chez Francis restaurant in honor of the Trio. There were many prestigious guests and a television crew was slated to film the Trio as it left the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées and arrive at the restaurant. Istomin used his back pain as a pretext not to go to Rainer’s dinner! Trapp related how Rainer, highly embarrassed, managed to reach Istomin on the phone and begged him to come and bring along the friends with whom he was dining. Istomin politely but firmly refused. A few days later, Istomin had a meeting with Rainer to discuss his future in France and the rest of Europe. It should come as no surprise that Rainer did not show a great deal of goodwill in carrying out his projects. It is unfortunate that this Beethoven series, in which he had distinguished himself so much, could not give a significant boost to his European career.

Rainer retired in 1977. Istomin subsequently entrusted his representation in France and the coordination of his activities in Europe to Opéra et Concert, a company founded in 1973 which at that time was managed by Martin Engström. Opéra et Concert maintained the links with the managers who already worked for Istomin in different countries: Sofia Amman in Italy, Harold Holt in England and now Andreas von Bennigsen for Germany and Austria, two countries where he had finally agreed to perform.

The results of Opéra et Concert were disappointing. In France, the 1970s were a prosperous period for Istomin, thanks to Pierre Vozlinsky who was currently the director of the French Radio and Television Music Department. The 1980s were less successful. Vozlinsky’s successors at Radio France hastened to remove from their lists the musicians he had regularly invited. As for Television, it abandoned almost every program dedicated to classical music. Shortly afterwards, Pierre Vozlinsky became the general director of the Orchestre de Paris, a prestigious orchestra created in 1967 by two of Istomin’s friends, André Malraux and Charles Munch. Vozlinsky was eager to invite Istomin, but Daniel Barenboim, who had been appointed music director, was opposed to this. Relations between the two pianists were apparently cordial, but their concepts of music and career were too far removed. Apart from the inevitable slowdown of his activity in France, Istomin’s main reproach to Opéra et Concert was its inability to coordinate his European calendar. He wanted to play more in Europe, even if the fees were significantly lower. He was upset by the deterioration of American musical and political life and found greater satisfaction in his contacts with European musicians and audiences.

In actual fact, the number of Istomin concerts in Europe was steadily increasing. He played almost every year in Great Britain, France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Switzerland, as well as in Israel. Taking in account other more irregular countries such as Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, Greece, Poland, and Portugal, this resulted in an annual total of at least forty concerts. But these engagements, scattered throughout Europe, left gaps in his schedule and forced him to cross the Atlantic on a frequent basis. This was all the more troublesome for him because he suffered a great deal from jet lag, and needed almost a week to acclimatize when he arrived in Europe! Istomin felt that the task of coordinating this activity into two or three coherent periods was perhaps difficult, but not insurmountable. In 1986, he decided to abandon Opéra et Concert, and on the advice of Jean-Bernard Pommier, to turn to the young, dynamic and ambitious Dutch manager Marco Riaskoff. He also changed his representation in several countries, returning to Valmalète in France and moving to Ingpen & Williams in England. He only kept on Sofia Amman, who had always worked remarkably well for him in Italy. Her father, who was president of the Società del Quartetto in Milan, had been close to Casals and had engaged Istomin in 1950 for his first concert in Italy. Unfortunately, she retired shortly after and proved to be irreplaceable.

At first, the new system set up with Riaskoff seemed to work very well. Istomin spent a large part of the summer of 1986 in Europe for the first time in many years, with concerts in Spain, Portugal, Switzerland and France. But these initial hopes soon gave way to dissatisfaction: the schedule remained very fragmented and difficult to deal with, especially since Istomin was planning to bring his own pianos. He eventually abandoned Riaskoff, keeping on only a secretary.

Detrimental consequences

Istomin was probably asking too much from his managers! Only a very few found favor in his eyes, because they gave priority to music over money. Istomin could not tolerate the way an artist was considered to be a commodity. He reacted the same way with baseball, where players were sold or traded like cattle!

Istomin was probably asking too much from his managers! Only a very few found favor in his eyes, because they gave priority to music over money. Istomin could not tolerate the way an artist was considered to be a commodity. He reacted the same way with baseball, where players were sold or traded like cattle!

He interceded many times with managers and organizers in favor of pianists he valued and whom he felt did not have the engagements they deserved. He did this for many pianists, including Claude Frank, Jean-Bernard Pommier and Yefim Bronfman in the early days of his career. He did this also for Clara Haskil, and most likely was highly amused to read the reaction of the critic for the Herald Tribune who, amazed that she had not been invited to America for 28 years, asked these questions: ”What do impresarios think about? Are they all asleep?”

When Istomin was dissatisfied and felt that there was a lack of respect and professionalism towards music and musicians, he did not hesitate to speak his mind in a very direct, sometimes abrupt manner. This attitude and straightforwardness were very damaging to his career. Two events were crucial: the incident with Michael Rainer and the refusal to follow Rostropovich’s advice to entrust his management to Ronald Wilford. Istomin was fully aware that both were in a position to play a key role in giving a new impetus to his career: Rainer in Europe, after the immense impact of the Beethoven cycle; Wilford in America who could have renewed the ties with the great American orchestras that no longer invited him. But for Istomin, it was inconceivable to give his allegiance to two unscrupulous managers for whom he had no respect. His unwavering moral uprightness always prevailed over the interests of his career.